[3] From

Rainstorm

(1980-1989)

Books of His Poems

On His Works Home

[1]

[2]

[3]

[4]

[5]

[6]

[7]

[8]

[9]

Selected Poems of Chen Li

Translated by Chang

Fen-ling

[3]

From

Rainstorm

(1980-1989)

•Song of Big Wind •Rainstorm •February •Autocracy

•Imitation of Atayal Folk Song : Passion / The House / The World / The Moonbeam in the Valley•Street Mirror •The Distant Mountain •Shadow Fighters

•Listening to

Winterreise on a Spring Night

•Taroko Gorge, 1989

•The Last Wang Mu-Qi

Thirty years old. The timid look of an infant.

Awake from a nightmare

again at five o'clock.

There is still a teacher to give you tests,

there is still a secret agent to find fault with you,

there are still military instructors, tutors, and disciplinary patrols to temper your

behavior,

to evaluate your honesty.

You wash your face, brush your teeth,

and before going to the toilet finish the poem you started reading last night before you

went

to bed.

Pickles. Motorcycles.

Flag raising. Good morning, teacher.

Jogging on sunny days.

Opening and closing an umbrella on rainy days.

A big wind is blowing,

blowing on the fog of a century's depression,

blowing on the dust accumulating on office desks,

blowing on the filth gathering in corners of local-news pages,

blowing on banality,

blowing on pedantry,

blowing on bookbags,

blowing on the safety helmet of the personnel director.

A big wind is blowing,

blowing on unbearable tears of one thousand years,

blowing on travelers stumbling over thorns,

blowing on starlight thinking in the dark night,

blowing on furious-looking old writers of futile passion,

blowing on widows with hatred in dreams and blood in hatred,

blowing on manure,

blowing on green grass,

blowing on wild roses in little sisters' hair.

Thirty years old. The

heavy steps of a tortoise.

Still seeming capable of pride.

Still seeming able to laugh wildly.

Cold tea. Hot sweat.

Going upstairs. Class dismissed.

Ever-twinkling traffic lights all the way. Slogans.

History. Black fog...

"A big wind is blowing, blowing on what?"

On all the people with love and

tears.

(1982)

I hear the rainstorm

shouting at us,

ten thousand acres of trembling starlight and shadows.

I hear the vast ocean crying for her lost babies,

dark sighs and breaths.

Rotten night,

rotten night.

An ideal has died here.

Do you see that?

Rotten night,

rotten night.

An ideal is about to resurrect.

Do you hear that?

I hear mud and sand

carrying pollen,

stinking water carrying honey.

I see excrement fostering rice,

rotten iron supporting insects' chirps.

Swinging among waves

is the world's rubbish:

kernels, waste paper, dead sperm.

Agitating among waves are people's words:

prayers, love poems, obscene shouts.

Tear the shore open!

Tear the shore open!

Do you hear them yelling,

washing our guardian dam of morality like the rainstorm?

Tear the shore open!

Tear the shore open!

Do you see their shadows,

rising from the secret ocean of life like giant trees?

And you— are you still the

proud cliff?

Plunge into that ocean!

Plunge into that ocean!

A great love is to be born here!

(1981)

February

Gunshots died away among the dusk flight of birds.

Missing

fathers' shoes.

Missing sons' shoes.

Footsteps

returning to every morning bowl of porridge.

Footsteps returning to the water of every evening washbasin.

Missing

black hair of mothers.

Missing black hair of daughters.

Rebelling

against the foreign regime while ruled by it.

Raped by the fatherland while embracing it.

Reeds. Thistles. Wilderness. Outcry.

Missing

calendars of autumn.

Missing calendars of spring.

(1989)

Translator's Note:

In this

poem, what the poet has in mind is undoubtedly the tragic event which occurred in Taiwan

on February 28, 1947 and caused the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Taiwanese

people. After the event, Taiwan was under martial law for nearly half a century. And the

tragedy remained a national taboo until 1987, when martial law was lifted.

Autocracy

They are the lawmen who tamper with grammar at will.

Singular,

yet accustomed to plural forms.

Objects, yet presuming to be subjects.

Hungry for

the future tense when young.

Indulged in the past tense when old.

Needless to

be translated.

Resistant to any changes.

Fixed

sentence patterns.

Fixed sentence patterns.

Fixed sentence patterns.

The only transitive verb: suppress.

(1989)

I would rather that my

love lived in a far-off place

so that I might talk to her more boldly and freely.

(Ah, how like flies and spiders and ants it is

to whisper in the ear only! )

I might take her hand, kick her feet

without having to be afraid of her squint-eyed and broad-shouldered uncle and aunt;

I might praise and sing at the top of my lungs

without having to fear the nightingale across the street should mimic it or spread it out.

I would rather that my

love lived in the snowy north.

There, in heavy drowsiness and a tremor

she will recall the nocturnal sky of the south more clearly:

the sweat in May, the heat in July.

Translator's Note:

Atayal is one of the aboriginal tribes in Taiwan.

The "valley"

in

the poem "The Moonbeam in the Valley"

refers to Taroko Gorge,

a national park

located in Hualien, Chen Li's hometown.

The Atayals are the original inhabitants of Taroko

Gorge.

Merry-go-round. A city

park on Sunday afternoon.

In a ten-dollar song operated by machine

the world and childhood went round slowly.

My daughter and I, sitting at two opposite points of a circle,

rode our respective toy horses parading in the land of the fairy tale.

Motionless stone lions, stone elephants, stone giraffes,

joined in the prancing parades in a daze.

The green mountain, green rivers, the Martyrs' Shrine,

revolved with us as well.

We galloped in the overlapped time and space,

her childhood chasing my childhood.

I turned around, seeing my father seated behind her back

chased by my swift-moving childhood.

The Martyrs' Shrine

on Sunday morning. My young father

ran up and down the steps with Mother and me.

I was eating sushi, Mother was singing sweet songs of flowers.

Father talked with Mother in Japanese interspersed with Taiwanese.

A military truck went down the hill loaded with soldiers.

By the suspension bridge, two aboriginal women

walked from the Meilung Stream with newly-caught clams on heads.

We went up to rest under an iron war-horse carved with 'Recover Our

Territory'.

Ma said the Martyrs' Shrine used to be a Japanese temple.

I asked what was the difference between a martyrs' shrine and a temple.

Pa said a temple was built to worship Japanese gods, while the Martyrs' Shrine

was to worship soldiers killed by the communists, or

martyrs caught by the Japanese.

I asked if Grandpa's

third brother was a martyr, who was caught after the retrocession of Taiwan.

Merry-go-round. A city

park on an autumn afternoon.

The history losing weight in the whirling circle.

The gunshots from the martial prison behind the bamboo groves.

Cicadas' chirping. Reeds.

Japanese concrete lanterns coming up all the way along the stone steps.

Childhood. Wonderland. My daughter and I

sat on the whirling mechanical horses, listening to our respective nursery rhymes.

"A white egret, driving a dustpan, to the stream bank..."

Sausage sellers, ice cream peddlers,

hot dog and tempura peddlers.

The ten-dollar mechanical nursery rhyme stopped abruptly

in the noise of reality. I sat on my wooden horse,

someone calling, "Papa, Papa, let's go home."

An autumn afternoon. The

shadow-lengthening Martyrs' Shrine.

I rose, with my daughter in my arms,

recalling to mind the nursery rhyme she had just learned from her grandma:

"Silver moonbeams, a learned scholar, riding a white horse, across the lily pond..."

(1989)

Translator's Note:

"sushi": a Japanese dish consisting of small cakes of cold cooked rice flavored with

vinegar, typically garnished with strips of raw or cooked fish, cooked egg, vegetables,

etc.

"tempura": a Japanese dish consisting of shrimp,

fish, vegetables, etc. dipped in an egg batter and deep-fried.

In the second stanza, the historical background of Taiwan is implied through the dialogue

between an innocent child and his father:

Taiwan, once ruled by the Japanese, is now

governed by the Nationalist Party of China (Kuomintang).

Different rulers give different

definitions of "martyr"—

for Kuomintang, only the soldiers captured

or killed by the Japanese or the Communist army are martyrs,

while the Taiwanese killed in

"the Event of February 28"

are regarded as rebels. The wheel of

politics toys with the fate of the Taiwanese.

Yet, when history loses "weight in the

whirling circle," the merry-go-round with family love as its axis can still gallop and

sing.

A Prayer for My Daughter Not until the whole street has fallen asleep

You may well doubt,

but you must believe in the sincerity of life:

every flower is the prettiest,

every language is the best.

Every day you hear your mama chatting in Hakka dialect with Granny.

Isn't it nice?

Every day you see in cartoons and fairy tales

'funny' characters.

Aren't they beautiful?

You may well stick to the good, but needn't be obstinate.

You may well seek after perfection,

but needn't suffer for not being perfect—

Lily, my Lily,

I expect you to stand on your own land independently,

observing the world aloofly, conducting yourself passionately.

I expect you to take the world as it is open-mindedly,

all its joy and sorrow, its hatred and love.

I'll pray for you again before daybreak:

let's breathe with the world,

let's work and rest with the world.

(1989)

Mother bade me to buy some

green onions.

I passed Nanking Street, Shanghai Street,

and Chiang Kai-shek Road (which sound strange

nowadays), and then I reached

Chung-hua Market.

I said in Taiwanese to the vegetable saleswoman,

"I want to buy some green onions!"

She handed me a bunch of green

onions smelling of mud.

When I got home, I heard the Holland peas in the basket

telling Mother in Hakka dialect that the green onions were brought home.

I sipped the Japanese soup in the

morning as if sucking Mother's breast

and took it for granted that miso shiru was my mother tongue.

I ate the pan bought from the bakery every evening,

not knowing that I was eating the bread with Portuguese pronunciation.

I put the scrambled eggs into my lunch box, put my lunch box into my satchel,

and ate my lunch stealthily after every class.

The teacher taught us music, the teacher taught us Chinese,

the teacher taught us to sing "Counter-attack, counter-attack,

counter-attack the Chinese mainland,"

The teacher taught us arithmetic:

"If each national flag contains three colors, how many colors

then do three flags have?"

The class leader said there were

nine, the vice-leader said three,

the green onion in my lunch box said one.

"Because," it

said,

"Whether

in the soil, in the market, or in the scrambled eggs with dried radish,

I am the green onion,

the Taiwanese green onion."

I traveled around with the empty

lunch box smelling of green onion.

The noise in the market called my name zealously in the box.

I struggled over the Brahmaputra River, the Bayenkala Mountains,

and the Pamirs (which don't sound unusual

at all now),

then I reached the Green-Onion Mountain Range.

I said in Taiwanese Chinese, "I want to buy some green onions!"

The vast Green-Onion Mountain Range

gave no answer.

There was no green onion in the Green-Onion Mountain Range.

All of a sudden I am reminded of

my youth.

Mother is still at the door waiting for me to bring back green onions.

(1989)

Translator's Note:

Taiwan has been coveted by many countries since ancient times. It

was visited by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, colonized by the Dutch and the

Spanish

in the seventeenth century. After that, it was governed by Zheng Chen-kong and the

Manchus. In 1895, it was ceded to Japan, which ruled over it

for fifty-one years until the

Kuomintang government took it over in 1945.

Under the reign of so many different rulers,

the culture of Taiwan has undergone the process of mixture and assimilation.

Miso shiru is a kind of Japanese soup flavored with

miso, a food paste made of soybeans, salt, and, usually, fermented grain;

pan in Taiwanese means

"bread," yet it is actually a word borrowed

from Portuguese.

Scrambled

eggs with dried radish is a

typical Taiwanese dish flavored with green onion.

The Bayenkala Mountains, in the eastern Tibetan Highlands, are

where China's two longest rivers, the Yangtze River and the Yellow River, originate.

The Green-Onion Mountain Range (the Pamirs are part of it) is a mountain

range in southwestern Sinkiang, known as the ridge of Asia.

The journey of buying green

onions can be seen as a process of returning to the native land.

"There was no green onion

in the Green-Onion Mountain Range"

because the poet has come to realize that

his roots are in Taiwan.

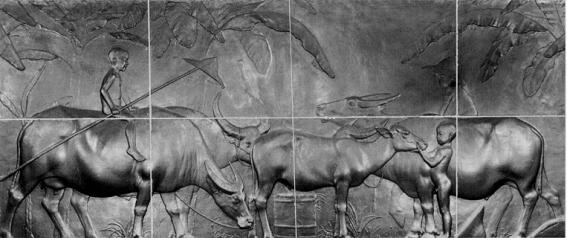

Those officials from the

north swarmingly

stepped down the dim stone stairs, some

leaning on walking sticks, some coughing lightly.

Accidentally bumping against a wall with a relief of water buffalo on it, they stopped.

"Water buffalo?" said one of them.

"Things left behind since the Japanese Occupation times.

Ha, those ignorant Taiwanese buffalo, fatalistic and naive..."

They followed an increasing number

of visitors into the hall ablaze with lights

and seated themselves in the old hall of the viceroy office of the colonial period,

chatting and executing the Constitution for the people who they had never acted on behalf;

what they chewed in the mouth tired of speech might be

Taiwan sugar, which they had had so much as to suffer from diabetes.

Drinking tea, urinating, on the laboriously-carved dreams of the people,

why should they bother to tell whether bananas or barley is grown in the soil under the

buffalo's feet?

Buffalo are buffalo even if they are led to Peking.

I am thinking in the long

night about the relief in the dark corner.

Five water buffalo, foundling each other joyfully on the green land,

melt the day's sweets and bitters together with their master

in a brief yet comfortable rest.

Dream-like green grass, water-like fine wind.

They turn to accept the earth's caress after the exhausting plowing.

That naked shepherd boy may be you, may be I,

may be our unborn offspring.

With a long hoe and a short bamboo hat, he plays with the cattle

on the mid-summer evening of the island.

They plow their own fields, being their own masters,

reaping the vast splendor of sunset, and the pure moon.

Five water buffalo, stout as thick and callous palms,

giant-like, are stamped into the breast of history

and reach the heart of darkness—

reach the newly-completed

city art museum.

That day, along with the students visiting in a queue the government-operated memorial art exhibition,

I stood before the shining bronze water buffalo.

I saw more clearly the secret of the island.

Lingering among those still bright and beautiful paintings and sculptures,

I found what I walked into was not the art history of the Japanese Occupation times,

but the dreams of the island, the heart of the history.

How far-away and vague those times were!

Sculpturing his people's images under the oppression of a different race,

soaking his body in the mud of his native land,

Huang Tu-shui, how transient yet gigantic a life!

I imagine those pioneers plowing and carrying on their backs this land like water buffalo.

Their passion, guts, perseverance,

and wisdom

go deep into earth like the ever-dripping rain,

blossoming and yielding fruit in desolation and taboos.

Buffalo are buffalo even if they have never been to Peking.

(1989)

Author's Note:

The Portrait of Water Buffalo

was the

famous work of Huang Tu-shui (1895-1930), a gifted, pioneering Taiwanese sculptor in the

early 20th century. This work of sculpture is now displayed on the wall in front of the

stone staircase between the second and the third floor behind the Kuanfu Hall in Taipei.

Recently the Council for Cultural Planning and Development appropriated funds to make two

bronze copies of it and presented them to Taipei City Art Museum and Taichung Provincial

Art Museum. Wei Qing-de, a poet, once wrote about the sculpture: "This

masterpiece, eighteen meters in length and nine meters in height, represents in

relief a mid-summer banana orchard: the gentle breeze blows, green leaves

flutter, five water buffalo fondle each other on the green pasture, two naked

shepherd boys look innocent and carefree— one sitting on the back of a

buffalo, with bamboo cane in hand, ...the other standing by a buffalo, passing his hand over it. The scene

poetically forms a picture of serene and peaceful landscape of the south."

Translator's Note:

The poem is not only a tribute to Huang Tu-shui's artistic

accomplishments, but an attempt to recapture through his work the suffering and tough

images of the Taiwanese people and to go deep into the profound secrets and dreams of this

island. To the Taiwanese who have long been governed and exploited by foreign regimes, the

serene and peaceful scene in Huang Tu-shui's relief

The Portrait of

Water Buffalo is symbolic of ideal life—

self-contented

and carefree— in which one reaps the fruit of hard work and in which social justice is not

a faraway dream.

"Buffalo are buffalo even if

they are led to Peking" is a

Taiwanese proverb, whose equivalent in English may be "The leopard cannot change its

spots." Chen Li subtly transforms it into: "Buffalo are buffalo even if they have never

been to Peking," which may be seen as an assertion of the independence of the Taiwanese

people from the Chinese mainland.

Street Mirror I don't want to say there is poetry in all mirrors

just like us, once carried away by love in our maidenhood.

(1983)

The Distant Mountain

The distant mountain gets more and more distant.

Once, in the morning of childhood,

Shadow Fighters We ride to work on gray shadows in the morning white as soybean milk.

Listening to

Winterreise on a

Spring Night

—for Fischer-Dieskau

The world is getting old,

laden with such heavy love and nihilism.

The lion in your songs is getting old too,

still leaning affectionately against the childhood linden tree,

unwilling to give in to sleep.

Sleep may be desirable,

when

the past days are like layers of snow

covering human misery and suffering.

It may be fine to have flowers in one's dream,

when the lonely heart is still seeking green grass in the wilderness.

Spring flowers bloom on

winter nights,

boiling tears freeze at the bottom of the lake.

The world teaches us to hope, and disappoints us too.

Our lives are the only thin paper we have,

covered with frost and dust, sighs and shadows.

We dream on

the fragile paper—

none the lighter for all its shortness and thinness

We grow trees in the dream which has been erased time and again,

and return to them

each time we feel sad.

I am listening to Winterreise

on a spring night.

Your hoarse voice is the dream in my dream,

traveling along with winter and spring.

(1988)

Author's Note:

3

You watched them gradually

leave their homes

and come to you,

those Chinese who were driven over the sea by the Chinese.

With postwar explosives,

nostalgia, bulldozers,

they dug new dreams among your tangled bones.

Some were missing in the tunnels they themselves had dug.

Some sank into the eternal abyss with falling rocks.

Some had one arm or one leg left,

standing in the wind like a persevering tree.

Some took off old robes, picked up hoes,

and nailed new doorplates by the newly-built road.

>From the girls whom they were newly acquainted with in the strange land, they learned

to graft, mix blood, propagate.

Just like the California plums, cabbages, Twentieth-century pears they grew time and

again,

they planted themselves into your body.

They hung new names of

places over the newly-built roads.

In spring,

their great leader, wearing medals of honor,

came to a place named Tianxiang to appreciate fallen plum blossoms.

They paved the royal couches on the hot-spring path, with hot vapor overhead,

reciting aloud

The Song of Righteousness.

But you are neither Huaqing Pool nor Mawei Slope,

nor the vague, distant Chinese landscape.

That famous painting master

Da-qian, with his trembling hand

touching his beautiful beard, more elusive than mountain clouds and fog,

painted nostalgia extravagantly with half-abstract splashes of ink on your concrete face.

They painted the picture of the Yangtze River on your mountain wall.

Yet you are not landscape, not the mountains and rivers in the Chinese landscape painting.

What hangs down from your forehead is neither Li Tang's Whispering Pines in the Mountains

nor Fan Kuan's Traveling among Rivers and Mountains.

To those who visit you in air-conditioned tourist buses

you are beautiful landscape.

(They are just like the Portuguese who cried out "Formosa"

in a strange tone when their ship

passed by the ocean in the east four hundred years ago.)

Yet you are not Formosa, though you are beautiful.

You are not the landscape to be carried, hung, or displayed.

You are living, you are life,

you are the great and truthful existence to

those people of yours,

who vibrate and breathe with the pulse of your veins.

4

I'm

looking for the foggy dawn.

I'm looking for the first black long-tailed pheasant that

flew over the gorge.

I'm looking for the indigo and the euphorbia that peeped at

each other through crevices.

I'm looking for the red knees of the setting sun that chased

the flying squirrels.

I'm looking for the calendars of trees that changed their

colors with the changes in temperatures.

I'm looking for the

tribe of wind.

I'm looking for the rites of fire.

I'm looking for the footsteps of mountain boars that echoed

with the sound of bows.

I'm looking for the bamboo houses of dreams that slept on

the pillows of floods.

I'm looking for architecture.

I'm looking for navigation.

I'm looking for the crying stars in mourning.

I'm looking for the mountain moon which, like a hook, hung

up the bloody night and the gorge.

I'm looking for the fingers that tied themselves with wires

and hung down thousand-foot-high cliffs to

explode

with the mountain.

I'm looking for the light that dug through the wall.

I'm looking for the skull that hit the bow of a ship.

I'm looking for the heart that was buried in strange soil.

I'm looking for a suspension bridge, a song without a

shoelace maybe.

I'm looking for the caves of echoes, a group of significant

vowels and consonants:

Tangarao, Bunkium, Tupido,

Tanlongan, Losao, Teruwan,

Topogo, Sumeg, Lupog,

Kobayan, Balanao, Botonof,

Kumoxel, Kalagi, Baga-Paras,

Kalapao, Tabula, Lapax,

Qesia, Busiya, Tassil,

Sexengan, Sidagan, Sikalaxen,

Qaugwan, Tomowan, Bolowan,

Vetodan, Putsingan, Senlingan,

Daoleg, Degalan, Degiag,

Sakadan, Palatan, Sowasal,

Bunayan, Bololin, Tabokyan,

Owai, Doyun, Batakan,

Dagali, Xoxos, Waxel,

Sikui, Bokusi, Mogoyisi.

*

5

I'm

looking for the cave of echoes,

pondering over the secret of the humble residence on earth

in a drizzly chilly spring.

When autumn came, they traveled together on the mountain path in the gorge.

What were waiting in the woods or by the stream

might be a group of suddenly-swarming monkeys,

might be two ownerless bamboo houses standing silently

by the desolate plowland.

Farther into the ancient path, they crossed a shrub of weeds

and encountered again the Japanese army trench lying in ambush.

Still farther on was an aboriginal hunting hut built of thatches,

with a couple of broken pottery pieces left by

the latest party of archeologists.

We pass by Huitowan

and arrive at the suspension bridge where stand nine plum trees.

At the place where Japanese policemen used to be stationed, a modern postman

happily distributes mail into different mailboxes.

It may be taken away by the old veterans living at Water Lily Pond,

who will cross the suspension bridge after two hours'

walk,

or by the women living at Plum Village,

who will come jolting all the way down in a cart.

You jolt along into the evening

village.

A healthy village boy runs excitedly to greet you.

His agile figure is like the wild deer that his maternal grandfather

hunted fifty years ago.

"Papa

has made good tea for you!"

Bamboo Village, the name of their

hometown,

so much like the poetry of Tang Dynasty his father read in his youth.

Just like the Atayal people who plowed and hunted here fifty years ago,

they crossed the sea and became the owners of the land,

growing their fruit trees, raising their children.

6

In the drizzly chilly

spring I ponder over the secret of

the humble residence on earth.

One toll pushes another.

Mountains stand beyond mountains.

I go up the steps, in the twilight approaching slantwise

the Buddhist chanting of the mountaintop temple.

Like the repeated beats of waves,

like your vast existence,

how simple and yet complicated the low, repeated chanting is—

tolerating the infinitesimal

and the vast,

tolerating the distressed and the joyous,

tolerating strangeness,

tolerating imperfection,

tolerating loneliness,

tolerating hatred.

Just like the low-browed benevolent Bodhisattva, you too are

the silent Goddess of Mercy,

impartially looking on the creation of the heaven and the earth, the death of trees and

the birth of insects.

The landscape speaks aloud, the skies are boundless.

I seem to hear the calling of life to life.

It goes through the crystal look of mountains and waters,

through the caves of eternal echoes,

and reaches tonight.

The towering mountain

walls lie flat at the bottom of my heart like a grain of sand.

(1989)

*Author's

Note:

The above are the

ancient names of the places in

Taroko Gorge. In the Atayal language they refer to

different meanings.

For example, Tupido, now called Tianxiang, originally means

"palm

tree;" Losao originally means "swamp;"

Tabokyan originally means "sowing;" Putsingan

originally means "a must for passing;" Bolowan originally means "echo."

Translator's Note:

Tianxiang: a place in Taroko Gorge, named after Wen

Tian-xiang (1236-1282), a heroic character in the last reign of Sung Dynasty, who fought

against the invaders only to be captured. Refusing to surrender, he was executed after

three years'

imprisonment. Before the execution, he wrote The Song of

Righteousness to express his loyalty and patriotism for the native land.

Huaqing Pool and Mawei Slope: names of places in Tang Dynasty. Yang

Yu-huan (719-756), Tang Xuan-zong's favorite concubine, bathed in the former, and was

forced to hang herself on the latter.

Da-qian (Zhang Da-qian, 1899-1983): a master of

the traditional Chinese water-and-ink painting. Living in Taiwan in the last years of his

life, he painted mostly the scenery of Mainland China.

Li Tang and Fan Kuan:

two major Chinese painters of Sung Dynasty, famous for their landscape

paintings.

Formosa (meaning "beautiful"):

another name for Taiwan given by the Portuguese who reached it in 1590.

The indigo (Indigofera ramulosissims) and the euphorbia (Euphor-bia tarokoensis): two rare species

of plants found in Taroko Gorge.

In Part Four,

Chen Li lists twenty images of search, which is an attempt to lead readers into

the heart of Taroko Gorge to look for its

origins, to take a glimpse at "the secret of the humble residence on earth." He also lists

forty-eight ancient names of spots in Taroko Gorge. To the outsiders, they may be

meaningless sounds, but to the Atayals, they are significant, vividly revealing the local

features. The reason why Chen Li makes such a long list is obvious: he is eagerly inviting

readers to go on a journey of retrospection to the lost culture of Taiwan.

Seventy days,

we have stuck to the profound darkness,

listening to the coal strata talking with water.

The recycling quiet is as everlasting as tapes,

playing back our breath in the minutest detail.

Roses between the lips,

maggots on the shoulders,

the glowworms breaking in remind me

of the morning stars I saw when I came.

The Keelung River is snaky and winding.

The maple trees at Sijiaoting are frost-cold.

Intricate veins,

mysterious mother.

We are thus warmly immersed in great

geology.

Iron spades, coal carts, dynamites, fears

have all slipped along cordage of time into cobwebs of sleep.

White night, black night.

Black night, white night.

Our hearts have gradually yielded to

the uproaring motors, to

the ancient water running more swiftly with every function of pumps.

The Keelung River is vast and imposing,

innumerable bats flutter across the only sky.

Indulged in pure narcissism,

I am surprised to hear my name called

along with cymbals, bells, wooden clappers, and sobbing:

"Mu-qi!

Mu-qi!"

"Oh, Mu-qi! Mu-qi!"

Are you asking me about

that sudden deafening explosion?

Eleven-forty,

the earth wept for her long-departed babies.

Tears initiated ten million horses of torrents,

which crazily galloped and ran after me

in the crooked and muddy tunnel,

tumbling baskets,

tumbling wooden shelves.

They went roaring by

before we could possibly recognize them.

I saw them trampling down Wan-lai's shoulders.

I saw them trampling down A-xin's forehead.

Yet we didn't even dare to escape

when we found more horses swarming in from all sides,

gnawing our eyes,

swallowing our hands and feet...

All these came suddenly,

just like the scene in

the movie we saw last spring,

and we had failed to surmise the sorrow in it.

How I envy you, the elder who is shuffling by the mine, left foot

crippled by the fallen rocks.

How I adore you, the young man who is still rolling about

in piles of coal.

But haven't I heard you talking and laughing loudly

when, having smoked the last cigarette, you sat on the morning wood waiting to get into

the mine,

when, hoeing lumps of coal, you let your sweat drip into the lunch boxes?

And on those nights of wine bottles as dark as abysses,

in the enchantment of dice as black and hard as coal mines,

haven't I seen you yelling,

panicking and trembling?

Seventy days.

We have been lying on death's breast so solidly.

In the profound and brilliant darkness,

our dreams

are the darkness far more brilliant and profound—

glittering maps,

eternal kingdoms.

Shu-xian, Huo-tu:

Did you see our newly-completed town of miners?

Neatly-planned buildings,

lush boulevards.

Zhao-ji and Qin-xiang are living right next door to Shuei-yuan, close to

the biggest aquarium.

The cinema is next to the beauty parlor.

The clinic, the opera house, the supermarket—

all half a minute's

walk.

Li Chun-xiong, who lived in Villiage Sandiao, has now moved to Gold Sesame D Building.

Zheng Chun-fa, who lived in Village Shangtian, has now moved into the 21st floor of Apollo Building.

Shenaokeng Road is to be made into a big park.

Fengzaita Road has long become our favorite golf course.

How about coming over to

see my newly-decorated house?

Next to the swimming pool is the garage.

The living room is in the front.

The kitchen is at the back.

On the second and third floors are the bedrooms of my six daughters.

(Tuesday and Thursday, Professor O of the Art College comes for their piano lessons.)

(Saturday, time for outdoor sketching.)

(Sunday morning, time for church-going with their mother.)

You must be wondering where we've hidden our bicycles.

We have had our driver's licenses for months.

Next to the dining room is our bathroom.

Next to the bathroom is our alcohol cupboard.

Next to the alcohol cupboard is our television set.

Behind the television set is my son's study.

(Bi-lu, my son,

I have received the telegram you sent on the 22nd

from Mazu. The "Wang Mu-tu"

on TV is none other than Daddy.)

The bread and butter of sunshine:

I don't have to be

the Wang Mu-qi who left home at five in the morning!

No more dilapidated and

low-hanging eaves.

No more jam-packed beds.

No more bedclothes too short to keep warm.

No more bowls waiting to be fed.

Eagerly-waiting wives lost in apprehension deep as a well; their thick and coarse hands;

and

on every washed, mended, torn, and stained dress,

the imperishable coal dirt of sorrow.

The bell rang—

children after school who played

hide-and-seek in the dark workmen's hut

at six p.m. (they never saw their sober fathers).

Coal dust, powdered milk,

greedily-gazing falling rocks,

explosion, loan, silicosis.

Recycling nightmares.

Recycling tapes.

Oh, memory, let me

erase you thoroughly.

A nine-year-old child,

I saw in the dream my dark-faced father return from the mine

and beat up Mother without saying a word.

A seventeen-year-old youth,

he watched confusedly his naked father

weeping secretly by the wall—

were you that young child too, when

a black umbrella

sent the sister to a faraway hospital

on a stormy night?

Seventy days.

Do you still send painful disease to the distant hospital?

Frail mothers,

aged grandmothers,

crooked ears,

broken vertebras.

Seventy days.

Do you still send tormented souls to the distant badminton court?

We are sticking to the

damp and dark rock strata, waiting

to be mined by sunshine.

Uproarious motors, sand bags, pumps.

Flags are swaying involuntarily in the dusky air.

Yu Tian-deng,

the first to run out of the third bypass on the right to inform us.

Yu Tian-deng,

who had four gold teeth in the upper jaw and whose second toe of the right foot was

missing.

Have you finally recognized his face,

his bravery,

his stupidity?

Get away from the wound of

pain.

Get away from the pit of despair.

Get away from anxiety, sorrow, and waiting.

Get away from paper money for the dead, ashes, and howling.

Let frightened children

return to their classrooms.

Let fainting old grandmothers return to their rocking chairs.

Hoes must work.

Bees must smile.

We are waiting here

because the proud crowns wouldn't shatter their hereditary jewelry.

We are waiting here

because the well-fed cows wouldn't take off their clothes of cream and

balsam.

Pottery makers who are trembling among the clay,

you will know.

Masons who are dozing among knives and stones,

you will know.

Writers who are writing rapidly on manuscript paper.

Congressmen who are urging emphatically before cameras.

We are waiting here

because of our fathers and brothers who are of equally humble birth.

We are waiting here

because of our fellowmen who have no other choice but to believe in fatalism:

Dying streams, black

steps.

Hollow rock strata, black temples.

Huge ink ponds, black elegies.

Boiling canyons, black choirs.

Sobbing moon, black bronze mirrors.

Coarse heavy linen, black blinds.

Tangled railroads, black veins.

Burning ore, black dams.

Black windows, eyes of

water.

Black grains, spades of water.

Black rings, chains of water.

Black ankles, reins of water.

Black names, dictionaries of water.

Black pulses, pendulums of water.

Black earthen jars, melancholy of water.

Black bedclothes, fury of water.

(Oh, memory, let me erase you thoroughly...)

Seventy days.

Are you asking me about the color of the lawn, the direction

of the setting sun?

The snakily winding Keelung River is vast and imposing.

Flags are flying.

Flags, are flying.

I see your dark thin figures prop up the newly-woven linens

in the evening wind.

I see your tin-white lips, your twinkling teardrops,

so huge and far away,

dripping toward me.

"Chen-man, my dear wife: No news after the departure.

Have you recovered from the cold?

On such a dark stormy night, how can I picture

you, standing before the window wearily,

staying awake from care and looking back at our daughters,

who have just fallen asleep?

It seems to have been a love story ten thousand years ago.

I saw you, a little girl with a bowknot on the hair,

come running to play at our muddy mining neighborhood.

Then I saw you, shy and tall.

Then I saw your furious father's harsh

eyes:

'A miner's child?!'

Yes, a miner's

child...

It seems to have been a

pledge one hundred thousand or one million years ago.

I watched you washing and sewing clothes,

nursing my children and sharing my surname.

But we had never filled up those three milk powder containers

with coins. The night was long.

The sleep got all the narrower for crowdedness.

Maybe we no longer need

any milk powder container.

Things are so expensive,

and you are so weak.

Is A-xue still feeling

pain in her shoulders?

I've read the letter from Bi-lu. I am

happy to know he is stout and healthy.

After his military service, you can take him to the mine

to see the boss.

The firm will surely offer him a job.

In the pocket of my raincoat

there is a pack of lotus seeds I've bought.

Do remember to take it out.

I have left four dry batteries with Uncle Chun-wu.

Lin A-chuan at Ruiju Road owes me one hundred and five dollars.

You may as well get it back from him in your free time.

You can buy a new pair of sneakers for Xiao-hui to wear at the athletic meet.

You should eat more and do less laundry work.

On such a dark stormy night, don't forget to bolt

all the doors and windows of the house..."

(1980)

Author's Note:The narrator of this poem is Wang Mu-qi, fifty-one years of age, a digging worker of Yongan coal mine. It was reported in the newspaper that his eldest son, Wang Bi-lu, who was serving in the army at Mazu, sent an urgent telegram home to ask if his father was sound and safe, because according to the news report on TV, a miner by the name of "Wang Mu-tu" (a miswritten form of Wang Mu-qi) was on the list of the victims. Besides his wife Wang Chen-man, Wang Mu-qi left behind him six daughters and a son,

who were all under age and the youngest of whom was still studying in primary school.

Books of Poems by Chen Li

In Front of the Temple

Animal Lullaby

Rainstorm

Traveling in the Family

Microcosmos

The Edge

of the Island

The Cat at the Mirror

New Poems

Microcosmos II

Introduction to Chen Li's Poetry

by Chang Fen-ling