[6] From

The Edge of the Island

(1993-1995)

[6]

From

The Edge of

the Island

(1993-1995)

•Morning Blue •Nocturnal Fish •Floating in the Air •English Class

•A Lesson in Ventriloquy •A Weightlifting Lesson

•A War

Symphony

•Three

Poems in Search of the Composers/Singer

•A

Love Poem Keyed in with Wrong Words Because of Sleepiness

•The Ropewalker •The Image Hunter •Furniture Music

•A

Prayer of Gears

•The Autumn Wind Blows

•Formosa,

1661

I waited in the crowded and noisy station

building

for the one who was late for the appointment

to appear on the bitterly cold winter day.

I carefully held a full cup of

hot tea,

carefully added to it sugar and milk,

stirring gently,

sipping gently.

You casually opened the slim collection

of Issa's haiku that

you had in your luggage:

"A world of dew; yet

within the dewdrops—

quarrels..."

This crowded station was a dewdrop

within

a dewdrop, dropped

in the tea deeper with every sip.

A cup of tea,

at first hot, turned warm, and then cold.

Things on my mind

ranged from poetry to dreams to reality.

In ancient times—

in the world of Chinese serial novels or

tales of chivalry—

it would be the time for a cup of tea,

in which a swordsman drew his sword wiping out the besieging rascals,

and a hero was enraptured and enchanted before the bed of a fair lady.

But modern time has changed its speed.

Within about the time for half a cup of tea,

you drank up a cup of golden fragrant tea.

A cup of tea

going from far to near and then into nothingness.

The one for whom you had waited long finally appeared

and asked if you would like one more cup of tea.

(1993) ▲

When dear God uses sudden death

to test our loyalty to the world,

we are sitting on a swing woven of the tails of summer and autumn,

trying to swing over a tilting wall of experience

to borrow a brooch from the wind that blows in our faces.

But if all of a sudden our

tightly clenched hands

should loosen in the dusk,

we have to hold on to the bodies of galloping plains,

speaking out loud to the boundless distance about our

colors, smells, shapes.

Like a tree signing its name with abstract

existence,

we take off the clothes of leaves one after another,

take off the overweight joy, desire, thoughts,

and turn ourselves into a simple kite

to be pinned on the breasts of our beloved:

a simple but pretty insect brooch,

flying in the dark dream,

climbing in the memory devoid of tears and whispers

till, once more, we find the light of love is

as light as the light of loneliness, and the long day is but

the twin brother of the long night.

Therefore, we sit all the more willingly

on a swing

interwoven of summer and autumn, and willingly mend

the tilting wall of emotion

when dear God uses sudden death

to test our loyalty to the world.

(1993) ▲

The

Olympic

—

Ars Poetica

Festive, competitive, and of five rings…

Of words and

words. Vaulting over the secular

level, with pens as poles. Creating new

aesthetics. (The definitions of pens were expanded

at several conferences of judges at the turn of the century, and

it was agreed that finding in poems stimulants other than

inspiration was

acceptable.) Take this poem

for example. Its title, "The Olympic"

(or "The Olympian"), is copied from the last line

of another poem of mine, having nothing to do

with inspiration. Even the form looks the same.

Words race with

words: a relay race. You can’t see

the baton passed or received. Straight smoke

above vast desert, round setting sun on long river, most

touching is the occasional bursting out (I miss you

near the end of every stanza) of the pure joy

of poetry. Pure

joy, game of the pairs: big robber; merry

widow; reed organ; green sleeves; autumn floods; Emanuel Kant.

Or in threes and fours: the dark eyes; lonely hearts club;

Where the bees suck; store of furniture; the Island Formosa; Shoot

the Piano Player; standing in the wind. Words in the wind,

standing,

running, shooting, grow to time, like a clown. Gentle wind

brings a small response, violent wind a great one. Let the craft drift over the

boundless expanse, and in whirling confusion, make the words sound together,

become harmonious, pure and clear, endlessly echoing—dignified and venerated,

enjoying themselves—a milieu which is festive, competitive, and of five rings…

Translator's note:

"Straight smoke above vast desert, / round

setting sun on long river" (大漠孤煙直,長河落日圓)

are

famous lines of the Chinese Tang Dynasty poet

Wang Wei (701-761).

"Where the bees suck" are the opening words of a song in Shakespeare's Tempest.

"Shoot the Piano Player" ("Tirez sur le pianiste") is the name of one of

Truffaut's films.

"Gentle wind brings a small response, violent wind a great one"

(泠風則小和,飄風則大和)

are words

written by the ancient Chinese philosopher Chuang Tzu (369?-286? B.C.).

"Let the craft drift over the boundless expanse"

(縱一葦之所如,凌萬頃之茫然)

are words

taken from a

well-known prose poem of the Chinese Song Dynasty poet Su Tong-po (1036-1101).

(1995) ▲

Between the whiteness of the night and the

darkness of the day,

you mercifully give me the morning blue,

your blue underwear, which is sought everywhere in vain,

your blue hair ribbon, which is raised with the wind.

You mercifully give me color blocks of

melancholy

to cover the empty heart that stays awake the whole night;

you mercifully give me moist soul

to melt the darkness of the day that follows in no time.

You are a blue sheep

running to and fro on the border of the dream.

With blue, hairy shadow you contradict my thought,

oppress my breath,

make me long for your blue eye rims,

and look forward to your blue tongue—

the blue waves that break at each

swallow and spit.

You leave me on the beach at the ebb tide,

picking up your lost blue necklace,

collecting your runaway blue mammary areolas.

You make me take the remainder of your saliva as the ocean,

as the Mediterranean,

and guard the narrow strip of the blue coast

between the huge continents of day and night.

Oh, goddess of evil, master of the morning.

(1994) ▲

In the night I turn into a fish,

an amphibian

suddenly becoming rich and free because of having nothing.

Emptiness? Yes,

as empty as the vast space,

I swim in the night darker than your vagina

like a cosmopolitan.

Yes, the universe

is my city.

Seen from any of our city swimming pools above,

Europe is but a piece of dry and shrunken pork,

and Asia a broken tea bowl by the stinking ditch.

Go fill it with

your sweet familial love,

fill it with your pure water of ethics and morality,

fill it with your bathing water which is replaced every other day.

I am an amphibian

having nothing and having nothing to fear.

I perch in the vast universe;

I perch in your daily and nightly dreams.

A bather bathed by the rain and combed by the wind.

I swim across

your sky swaggeringly,

across the death and life that you can never escape.

Do you still boast of your freedom?

Come, and

appreciate a fish,

appreciate a space fish that suddenly becomes rich

and free, because of your forsaking.

(1994) ▲

A spider, I imagine,

occupying a few branches

to spin out poetry—

transparent stanzas interweave an empire,

a self-contained sky

baptized by rain and wind.

(1994) ▲

There are five people in John's family.

His father is a doctor.

His mother is a nurse.

His brother is a senior high school student.

His sister is a junior high school student.

John is a junior high school student, too.

They have a big house.

They have a big TV.

They have a big car.

They have a big key.

Dr. Sun Yat-sen was born in November.

His birthday is a holiday.

John was born in November, too. But

his birthday is not a holiday.

Many people don't go to work on holidays.

Students don't go to school on holidays.

They can play computer games or sleep at home.

There are many animals in the zoo.

There are monkeys, rabbits, lions, tigers, elephants and bears in the zoo.

There are many desks and chairs in the classroom.

There are a teacher and fifty students in the classroom.

The teacher is writing on the blackboard.

The blackboard is green.

There are many beautiful flowers and birds in the park.

The flowers are red, yellow and white.

The birds are black and blue.

Mary's

father is sitting on a bench in the park.

He is looking at his dog.

His dog is running and playing.

It snows a lot in New York in winter.

It rains a lot in Taipei in summer.

Does it ever snow in Kaohsiung? (Give a brief, negative answer.)

No, never.

There will be a thundershower this afternoon.

There will be a basketball game tomorrow evening.

John and his friend Mary will go to the basketball game together.

He won't

go with his parents.

They will have a good time.

Does John like English songs?

Yes, very much.

Does John understand my Chinese?

Yes, but not much.

Does John often catch a cold in fall? (Give an affirmative answer in a complete sentence.)

Yes, John often catches a cold in fall.

(1994) ▲

A Lesson in Ventriloquy

Music,

Hong

Chung-Kun /

Poem, Chen Li

↑

腹語課

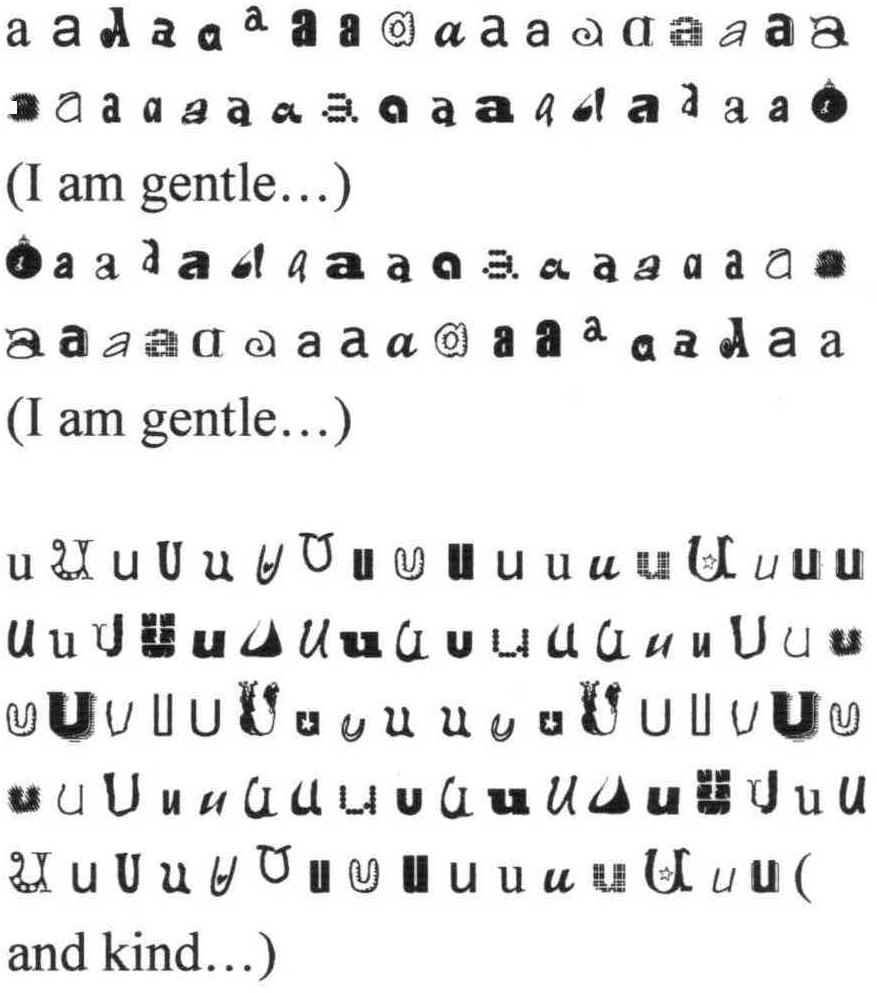

惡勿物務誤悟鎢塢騖蓩噁岉蘁齀痦逜埡芴

軏杌婺鶩堊沕迕遻鋈矹粅阢靰焐卼煟扤屼

(我是溫柔的……)

屼扤煟卼焐靰阢粅矹鋈遻迕沕堊鶩婺杌軏

芴埡逜痦齀蘁岉噁蓩騖塢鎢悟誤務物勿惡

(我是溫柔的……)

惡餓俄鄂厄遏鍔扼鱷蘁餩嶭蝁搹圔軶豟豟

顎呃愕噩軛阨鶚堊諤蚅砨砐櫮鑩岋堮枙齶

萼咢啞崿搤詻閼頞堨堨頞閼詻搤崿啞咢萼

齶枙堮岋鑩櫮砐砨蚅諤堊鶚阨軛噩愕呃顎

豟軶圔搹蝁嶭餩蘁鱷扼鍔遏厄鄂俄餓(

而且善良……)

Translator's Note:

Read for the first time, the poem may strike one as no more than a language game, a game that is likely to have been inspired and made possible by Chinese computer software (which allows one to punch in a romanized Chinese word and get a long list of homonymous characters in varying tones). Lines 1-2 put together thirty-six different characters with the "u" sound in the fourth tone, which are mirror-imaged in lines 4-5. The long catalog of characters is broken up only by the inserted parenthesized line in italics: "I am gentle..." In the second stanza, there are forty-four characters with the "o" sound in the fourth tone. Parallel to the first stanza, the two sets of characters here also form a mirror image of each other. The parenthesized, italicized line 12 completes the sentence, which begins in fragments lines 3 and 6: "I am gentle...I am gentle...and kind..."

What are we to make of this? First of all, we note the sharp contrast in typography. Lines 1-2, 4-5, and 7-11 form a rectangular block respectively, with a small corner of the third rectangle cut off by a single parenthesis in line 11. In terms of size, these rectangles take up much more space and look much larger and heavier than the parenthesized lines, which are less than one-third of the rectangles. Secondly, the rectangles and the parenthesized lines have different typefaces. Also in terms of form, there is perfect symmetry between lines 1-2 and lines 4-5, and almost perfect symmetry between lines 7-8-9½ and 9½-10-11. Symmetry is conspicuously absent in the parenthesized lines; in fact the poet uses several devices to avoid formal symmetry in these fragments, including using an odd rather than even number of lines, the repetition of "I am gentle..." twice in contrast to the one "and kind...," thus creating a 2-1 asymmetry in the complete sentence with lines 3, 6, and 12. All the line numbers with regard to the sentence are also multiples of three, another odd number. Finally, there are the asymmetrical punctuation marks and the odd position of the parenthesis at the end of line 11.

In addition to form, there is a most dramatic contrast in sound. Whereas "u" and "o" are both fourth tone, reading thirty-six u's and forty-four o's in a row creates a hard, monotonous, unnatural sound effect. (Can we imagine what it’d be like if the poem was read out loud at a poetry reading?) In contrast to the long strings of heavy sounds, the short sentence consisting of a few simple, mono- or bi-syllabic words, with an undulating cadence (with a fair distribution of all four tones), sound so much lighter, softer, more melodious and pleasant.

Further, in terms of syntax, the thirty-six u's and forty-four o's do not form a phrase or unified image, much less a meaningful sentence. In fact, if we examine these characters, most of them are obscure words hardly ever used in daily speech or even in writing. Grouped together in this particular typographical arrangement, they create an extreme effect of defamiliarization: for a Chinese reader, although she may recognize all the words, they look strange on the page. In contrast, although the words in the parentheses are small in number, they form a complete sentence, with the subject "I," the copula "am," and the predicate "gentle and kind," consisting of two adjectives combined with a conjunctive "and." Despite its minimalist syntactic structure, the sentence is a perfect sentence.

Finally, we note the semantic structure of the poem. The first word of both stanzas is the same character with two different pronunciations ( "u" and "o") and meanings ("to loathe or dislike" and "evil"). Both words, however, have negative connotations. The contrast between them and the words in parentheses— "gentle" and "kind"— is obvious.

Why is the poem called "A Lesson in Ventriloquy"? As the art of speaking without opening the mouth, ventriloquy connotes a discrepancy between appearance and reality, between outer form and inner substance, between "what you see" and "what you hear." Discrepancy clearly exists between the "u" and "o" sounds and the parenthesized sentence in the poem. Although the former presents an unpleasing appearance, the latter reveals the heart, which is gentle and kind.

(1994)

▲

Translator's Note:

(1995) ▲

A War Symphony

→ Hear Chen Li reading the poem → See animation of the poem

Translator's

Note:

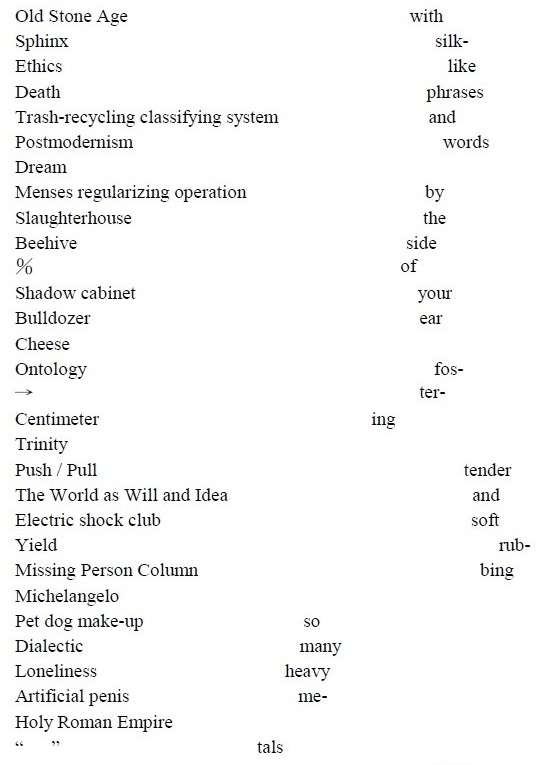

The Chinese character "兵"

(pronounced

as "bing") means "soldier."

"乒"

and

"乓"

(pronounced

as "ping"

and

"pong"),

which look like one-legged soldiers,

are two onomatopoeic words imitating sounds of

collision or gunshots.

The character "丘"

(pronounced as "chiou") means

"hill."

(1995) ▲

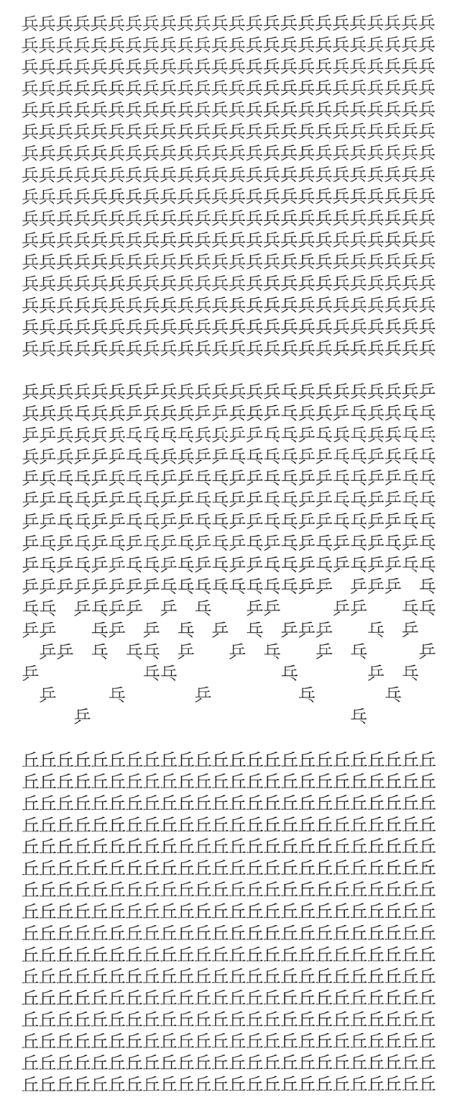

1 Starry Night

2 Wind Blowing over the Plain

3 Footprints in the Snow

Translator's Note:

Pachinko is a game of gambling with a lot of small metal balls whirling around in an upright box, popular in Japan as well as in Taiwan.

The titles of the second and third poems are taken from Debussy's piano work

Preludes.

The meanings of the four Chinese characters in the second poem are as follows—

噓

= hush

口 =

mouth

虛

=

empty

人

= man

(1995) ▲

A Love

Poem Keyed in with Wrong Words

Because of Sleepiness

My dare [dear], I swear that I love you for evil [ever].

I miss those wonderfool [wonderful] nights we spat [spent] together,

those sublind [sublimed] nights which are joyful,

gleetful [gleeful] and affected [affectionate].

I miss those wet [great] poems we read together,

those vivid and wicked [witty] images

which make me feel both hungry and food [full]

on wrong [long] and winding nights like tonight.

My horny [honey], my love for you will lost [last] for ever.

Among thousands of flowers, only one will I fuck [pluck].

I want [won’t] leave you

I want [won’t] let you be sexually harassed.

Our love is as poor [pure] and clean

as green penis [plants] carrying on photosynthesis

intercoursing senselessly [ceaselessly] in the sunlight and moonlight.

Our love is blessed by Dog [God].

(1994) ▲

Now what I sustain is, floating in the

air, your laughter,

your laughter, through the obscure quivering net.

What if a ball larger than a roof should be thrown over?

Would it drive you into sudden melancholy?

A ball like the earth, pouring onto your face the unfastened

islands and lakes (just like a wheelbarrow with a loose screw).

Those black and blue bruises are the collisions with mountains,

the metaphysical mountain ranges harder than iron wheels,

the metaphysical burdens, anxiety, metaphysical aestheticism...

And the so-called aestheticism, to me, who tremble in the air,

is perhaps only a restraint from a sneeze, an itch, with

the head still up.

What runs over you at the same time is the

joke system of

all continents and subcontinents, interwoven in your body like tributaries,

a joke not very funny: black humor, white terror,

red blood. Red, because you once blushed with your heart fluttering

for the beloved girl (of course you can't forget the hatred and bright red blood

aroused by jealousy and fury...) But you're simply a ropewalker

walking on the earth, yet discontented with only being a ropewalker

walking on the earth.

Now what I sustain are the subjects left

behind by the

departed circus: time, love, death, loneliness, belief,

dreams. Will you thus unpack the parcel before a houseful of

silent audience? The moment of sudden solemnity after roaring laughter.

You simply pull out, wipe, rearrange the earth's internal organs,

those spare parts that make the world move, sunshine leap,

the male and the female animals reach their orgasms...

They don't

even know why you stay there,

stay there (restrain from sneezing and itching),

a wingless butterfly turning a somersault where it is.

So you tremble in the air, cautiously

constructing

a garden of jokes on the dangling rope,

cautiously walking across the earth, propping up

the floating life,

with a slanting bamboo cane,

with a fictitious pen.

(1995) ▲

The

Image Hunter

—in memory of Kevin Carter

If there is a war far away, and the black

chessmen

carrying rifles, spears, and axes fight hand to hand against the fully armed

white chessmen on the street, if a chessman

falls down, wails, blood splashing around,

how will you, a hunter whose camera serves as a gun,

make quick movements, hold your breath, and push the camera shutter

as if triggering a gun to give another shot before

death departs, and hunt its most touching image in time?

If there is starvation far away, and naked

and skinny humans

embrace one another in the wilderness, awaiting Lord's supper of blood and tears

to feed their bodies, if a girl

falls weakly, head on earth, with a vulture behind her

waiting for the corpse with cruel greed,

merciful hunter, how will you

move slowly, restrain the sense of guilt, cautiously avoid disturbing

the food-seeking vulture and spoiling the perfection of the picture

so as to present the world with true and grievous art?

If there is a war far away, morality and

art,

conscience and duty, if the mosquitoes of death and of beauty

gather simultaneously on a living lump of

rotten flesh, poets who sit in the study reading about

the world, how will you wave the swats of reality and aesthetics

which have so very different graduations, how will you wind the springs

of suffering and passion, making fruit slack enough to flow out

juice, how will you develop the images of tragedy

with the pictures of words, how will you reconcile the contradictory compassion

with the compassionate contradiction?

Author's Note:

Kevin Carter

was a South African photojournalist born in 1960.

In May, 1994, a picture of a Sudanese

girl who was on the verge of dying of starvation and becoming the prey of vultures

(printed in New York Times, March 1993) won him the Pulitzer Prize for feature

photography.

Being awarded, Carter was criticized for capturing the scene at the cost of

others'

misfortune.

In July, 1994, Carter killed himself with carbon monoxide.

His last words were,

"It's a pity that in life

pain prevails over joy after all."

(1994) ▲

I read on the chair

I write on the desk

I sleep on the floor

I dream beside the closet

I drink water in spring

(The cup is in the kitchen cupboard)

I drink water in summer

(The cup is in the kitchen cupboard)

I drink water in fall

(The cup is in the kitchen cupboard)

I drink water in winter

(The cup is in the kitchen cupboard)

I open the window and read

I turn on the light and write

I draw the curtains and sleep

I wake inside the room

Inside the room are the chairs

and the dreams of the chairs

Inside the room are the desk

and the dreams of the desk

Inside the room are the floor

and the dreams of the floor

Inside the room are the closet

and the dreams of the closet

In the songs that I hear

In the words that I say

In the water that I drink

In the silence that I leave

(1995) ▲

Oh Lord, our

life is so,

so strugglingly

revolving, a set

of tooth-biting

gears, the planets

that bite and fall

ceaselessly, with you

as our center, with night

as our center.

What ties us is

the unfathomable

fear, the provocation

of omnipresent

darkness. We're the eternal

mechanism

led by others

yet leading others,

unable to twist off ethics,

morality, passion, and fury.

Oh Lord, we are

traveling in the universe,

the metal family

with grim hard edges,

an eye for an eye, a

tooth for a tooth, circling

in nothingness, the

lonely hedgehogs that

rub each other's

humble bodies to keep

warm. Please tolerate

our discord and

friction, tolerate

our daily trivial

dirty fight for

power and profit,

ceaseless

biting and falling:

a collective living body

that we can't but accept.

Oh Lord, we are

silent mills

revolving

in the prison of time, Sisyphuses

who push and grind

cyclically,

grinding desires, grinding

agony, grinding out

spots of mystic

ecstatic starlight

of powder, the heroin

that makes death dizzy,

the flowers of evil

that make night tremble. So

strugglingly we bite

and revolve because}

oh Lord, they will

follow the light and see

our hereditary

garden of soul.

(1995) ▲

The Autumn Wind Blows

The autumn wind blows down new sorrow

and the skull of the fatherland...

The autumn wind, on a summer street in

Taipei,

at the end of the century,

between the water lily pond and a pachinko house,

a middle-aged man, having just stepped out of the History

Museum, is dripping wet with sweat

which still smells of the shining black ink

in your paintings. He recalls to mind twenty years ago

when, in an imported hardback book in English,

he first bumped into your subtly magnificent landscape,

The Boundless Landscape is Absorbed in the Picture,

which is now hanging right on the eastern wall of the museum.

Those mountains, those waters, the same images of sail

were stamped, like a stab, in his chest just rid of

history textbooks. A college student accustomed to

the banana green and the rice yellow,

he casually opened the newly-bought book in English

to the vague scene of spring rain south of the Yangtze River,

to a gust of autumn wind.

The Autumn Wind Blows

Down the Red

Rain.

In a foreign-made Chinese painting album,

those frosty leaves, flying over the laterally-moving letters,

were printed vertically one by one in my heart.

I was the shepherd boy buried in the music of the flute, in your

paintings. The autumn wind blows down the red rain

on the territory of old dreams which die and revive

repeatedly. Sparse willows

are hung with new leaves; plum blossoms

are blown into spring.

In an age of taboos,

I peeped at you, who, on pure white paper,

dyed the woods in the mountains totally red

with timid guts and persevering soul.

To dye, or not to dye?

Whether it be an inspiration from Chairman Mao's poem

or an attempt to write biographies for the landscape of the native country,

you knew you were aiming at

ever-transcending creativity.

You broke the skull of the fatherland forcefully

to endow the landscape with new souls.

Three thousand abandoned paintings, one living life.

You made the landscape survive in you.

Cultural Revolution, armed strife, banishment, denouncement.

With threats under which even plants were taken for enemy troops

the ruler ruled over art.

With army-like grass and trees, with

knife-sharp brushes and ink, you liberated politics,

liberated such a beautiful land.

To dye, or not to dye?

Dyeing every grass, every tree

in every mountain, every water,

you gave the picturesque landscape

new pictures: shepherd boys on buffalo's backs,

autumn wind with red rain.

You gave the sorrowful autumn new sorrow.

At the end of the century, on a summer

street

between the water lily pond and a pachinko house,

a middle-aged man, having just stepped out of the History

Museum, is dripping wet with sweat.

Looking up, he is greeted by

a sudden gust of autumn wind.

He holds tight the Dajia straw hat

which comes near being blown away,

as if it were a new skull.

"The Landscape

of Guilin, the World of Dajia" :

a real estate advertisement occurs to him

in

the nostalgia which gets mixed up all of a sudden, and

in the red rain which is blown down ceaselessly.

Author's

Note:

The Autumn Wind

Blows Down the Red Rain (quoted from Shi Tao, a Chinese painter of Ming Dynasty), The

Boundless Landscape is Absorbed in the Picture,

and Dye the Woods in the

Mountains Totally Red (quoted from Mao Tse-tung) are titles of the paintings of Li

Ke-ran (1907-1989).

"Write biographies for the landscape of the native country"

and "Three thousand abandoned paintings"

are

the contents of two of his seals.

Translatorr's

Note:

Li Ke-ran:

one of the most renowned contemporary Chinese painters, whose Chinese name "Ke-ran"

(可染) literally means "can be dyed."

Guilin is a city in the northeast of Guangxi, in Southern China, famous for its beautiful

scenery.

Dajia is a town in Taichung, in the central part of Taiwan, famous for its straw

hats.

There is a Chinese saying, "The landscape of Guilin is the most beautiful in the

world" (桂林山水甲天下). But here in this poem Chen Li

cleverly transforms it into "桂林山水大甲天下", which can

be interpreted in two ways: one is that "the landscape of Guilin is by far the

most

beautiful in the world;" the other is that however beautiful Guilin may

be, Dajia is itself a world of unique beauty.

In the last stanza, the middle-aged man is

lost in the confusing nostalgia, which implies the dilemma many Taiwanese are in:

to be

linked to Mainland China ("the skull of the fatherland"), or to break away from it. The

poet seems to have made his choice:

he "holds tight the Dajia straw hat / which comes near

being blown away, / as if it were a new skull."

(1994) ▲

I've always thought that we are living on the cowhide

Author's

Note:

Bakloan, Tavacan, Dalivo, Sinkan, Tirosen, and Mattau are

names of communities of the

plains aborigines

in Taiwan.

The Sideia language and the Favorlang language are dialects of the

plains indigenes

(Sideia is also called Siraya).

Zeelandia was a city built on Tayouan island

(now called Anping, in Tainan) by the

colonists during the Dutch Occupation period

(1624-1662).

Provintia was a fort they built.

It is said that the Dutch offered to exchange fifteen bolts of cloth with the

aborigines for

a cowhide-sized piece of land.

After the

agreement was made, they “cut the cowhide into

strips and encircled

land more than one kilometer in circumference”

(See Lian

Heng, A

General History of Taiwan).

“Ge” was a unit of measurement used by the

Dutch, equaling about twelve feet five inches.

Twenty-five ges squared equals

one morgen. Five morgens make one zhangli.

(1995)

Books of Poems by Chen Li

In Front of the Temple Animal Lullaby

Rainstorm

Traveling in the Family

Microcosmos

The Edge of the Island

The Cat at

the Mirror

New Poems

Microcosmos II

Introduction to Chen Li's Poetry

by Chang Fen-ling