|

||||||||

|

Pursuing Indigenous Self-Government in Taiwan*

|

||||||||

Cheng-Feng Shih, Professor**Department of Public Administration and Institute of Institute of Public Policy Tamkang University, Tamsui, Taiwan P.O. Box 26-447, Taipei 106, TAIWAN (台灣) Tel: 886-2-2706-0962; Fax: 886-2-2707-7965 E-mail: ohio3106@ms8.hinet.net; HTTP://mail.tku.edu.tw/cfshih

|

||||||||

|

Introductions The 13 Indigenous Peoples[1] constitute roughly 2% of the 23,000,000 population of Taiwan.[2] Before the 2000 presidential election, Chen Sui-bien, candidate of the then opposition party, Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), signed a “partnership” agreement with leaders of the Indigenous movement in Taiwan in 1999. The next year, President Chen signed another agreement with these leaders and reconfirmed his determination to honor those pledged in the earlier agreement, including promoting indigenous self-governments. After his reelection in 2004, President Chen, to the surprise of the Indigenous Peoples, announce that he would put up an exclusive chapter for the Indigenous Peoples in the much discussed new constitution in 2006. While Indigenous leaders are endeavoring to draft such a constitutional bill for themselves, there are concerns that President Chen is only paying lip service to them. This article will examine what efforts have been made to arrive at the goal of self-government within the administration since the DPP came to power in 2000. The focus will be on comparing the two versions of Indigenous Self-Government Bill, especially how the notion of “nation-to-nation” is embodied. And then, we will examine how indigenous intellectuals have reacted to them. Finally, we will look into what barriers may have arisen on the road to indigenous self-government.

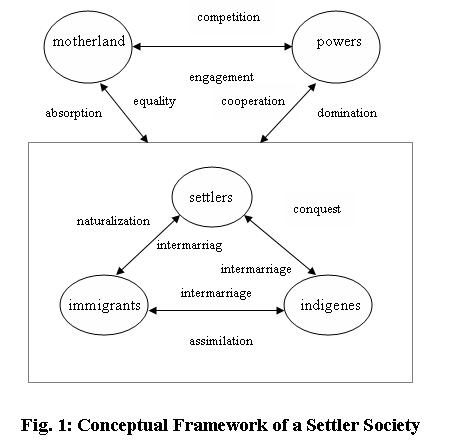

Taiwan is a settler society like Canada, United States, Australia, and New Zealand. Before settlers began arriving at the island four centuries ago, the Indigenous Peoples had resided here since time immemorial. From discovery, conquest, to settlement by the “others,” they still had gradually retreated to remote areas or to accept cultural assimilation. The state, seeking to become a modern nation-state, is playing a two-level game (Fig. 1): one the one hand, it has to resist forceful absorption by the motherland, China, and domination by neighboring power; on the other hand, it has to strike a balance among settlers, indigenes, and later-coming immigrants. Basically, it is a three-pronged task: state-making in the sense of securing sovereignty, nation-building in terms of forging common national identity, and state-building in the process of institutional engineering (2007).

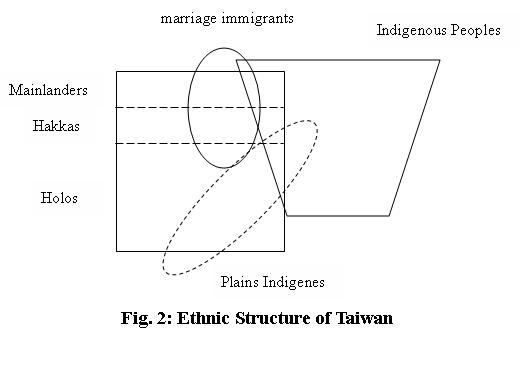

Nowadays, it is generally agreed that there are four major ethnic groups in Taiwan (Fig. 2): Indigenous Peoples, Mainlanders, Hakkas, and Holos (Shih, 1995). While the former are of Austronesian stock, the latter three are descendants of those Han refugees-migrants-settlers of Mongolian race who sailed from China as early as 400 years ago. Ethnic competitions would be found mainly along three configurations: Indigenous Peoples vs. Hans (Mainlanders+Hakkas+Holos), Hakkas vs. Holos, and Mainlanders vs. Natives (Indigenous Peoples+Hakkas+Holos). For the past two decades, the number of marriage immigrants from Southeast Asian countries and China has surpassed that of the Indigenous Peoples: yet, it is not clear whether they would constitute a new ethnic groups against the natives. Finally, there is a reclaiming collective identity of Plaines Indigenes, who had almost lost their indigenous characteristics until the 1930s. In the old days, they had chosen to Sincized themselves and become “human beings” in order to avoid systemic discrimination. In essence, these are actually Mestizos who have so far considered themselves Creoles. However, most of them are not officially recognized as indigenes by the government.

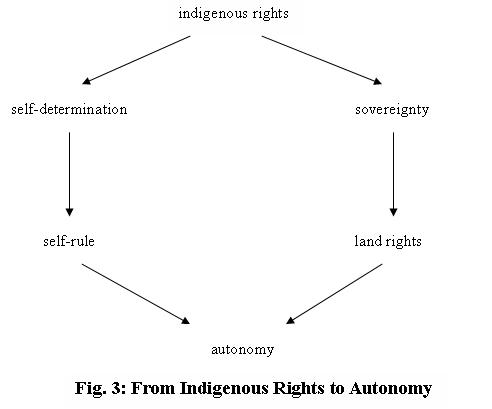

Efforts In the past two decades, the Indigenous Movement in Taiwan, based on the idea of inherent indigenous rights, has focused on three interlocked goals: the right to be indigenes, self-rule, and land rights (Fig. 3).

Being the Indigenous Peoples of Taiwan, they claim that they are not merely ethnic minorities but indigenes that deserve their rights enshrined in international laws. It is argued that Indigenous Peoples have never renounced their sovereignty seized by the aliens. Indigenous elites insist that indigenous lands dispossessed a century ago be returned to the Indigenous Peoples. Buttressed by the idea of self-determination, they demand the establishment of self-governments in place of present-day local administrative units. It is believed that only self-rule without being patronized can lead to true autonomy where the Indigenous Peoples can decide what is the best for themselves. To certain degree, the government seems to realize that protecting indigenous rights is a gesture of reconciliation. So far, two versions of the Indigenous Self-Government Bill have been prepared. Bill A, while excessively detailed in light of Continental Laws, was drafted by experts on local government and fashioned after the Local Government Law in the spirit that the authority of the indigenous government is delegated by the central government. It was then replaced by Bill B after been stalled during the process of cross-ministry reviews, in the hope that this simplified version would be a model of procedural law rather than substantial one for future drafting of separate autonomous statute, read “treaty,” between each indigenous people and the central government. Tactically speaking, it was purposefully calculated that this reduced bill would ease the painstaking process of lawmaking. However, after some heated deliberations in the Legislature, the government was forced to withdraw the bill as indigenous legislators complained that no adequate indigenous rights had been guaranteed in the bill. It was forcefully insisted that some itemized list of indigenous rights, especially financial support in certain proportions to the annual national budget, be specifically recognized in the bill. Otherwise, it was contested that the bill-in-principle was nothing but an undisguised hoax to deprive the Indigenous Peoples of what they deserve. The most fundamental issue raised is whether the idea of indigenous sovereignty is compatible with the existing state’s indivisible sovereignty. In other words, it is suspected that how sovereignty is to be shared by the Indigenous Peoples and the state. It is also doubted whether it would challenge the territorial integrity of the state if the Indigenous Peoples choose to exercise their right to self-determination and declare outright independence. Some even argue that the Indigenous Peoples have never possessed any right to the lands except the right to exploitation. Others have gone so far so to dismiss the whole notion of indigenous rights. Strongest resistances come from the Bureau of Forest Services and from the Bureau of Water Resources, whose jurisdictions largely overlap with the designated areas for indigenous self-governments, particularly the former. While daring not to speak out openly, some DPP elements have suggested that the emperor’s new clothes be thrown into closet as a responsible ruling party, implying that those promises to wood the Indigenous Peoples are nothing but empty electoral rhetoric during presidential campaigns. Engulfed in the disillusioned clouds, an Indigenous Basic Law was unexpectedly passed by the outgoing legislators in 2005. Praised as the Indigenous Constitution, the law may be considered as a de facto treaty between the Indigenous People and the state. Essentially a synthesis of abstract principles and concrete protections of indigenous rights, the law designates the formation of an Enacting Committee under the Executive for its enforcement, where two-thirds of its members be reserved for the Indigenous Peoples.[3] It also requires concerned ministries and agencies to revise relevant laws and statutes in its conformity in three years. Last but not least, it attaches a sting that there shall be a separate chapter for the Indigenous Peoples in the intended Bill of Rights. Within the Council of Indigenous Peoples, a working group made up of ministerial delegates, indigenous representatives, and scholars, was established in early 2006 to assist further considerations of the abovementioned enacting committee. Since its inception, its members have been working under four substantive groups: administration, education-culture, economics-development, and indigenous lands. While ministerial delegates are ready to protect their constituencies, indigenous representatives are similarly eager to defend their inherent rights. This sometimes leaves scholars as crucial arbitrators when disputes arise. When those civil servants throw doubts upon, if not ridicule, the whole idea of indigenous rights, non-indigenous participants qua scholars have to come up with legitimate rationales upon international laws, political philosophy, and practices from other countries that lie under the Indigenous Basic Law. From time to time, it is argued without valid proof that indigenous rights may conflict with national interests and that therefore their fulfillment be suspended. At this juncture, scholars have to point out that there is no necessary contradiction between indigenous rights and national interests; even if there is, some compensatory measures are warranted. At times, in addition to professional knowledge, scholars have to work on their conscience while walking on a thin line between the quarreling parties, so that they would not be suspected of being agents of either.

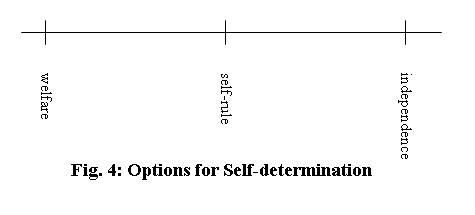

Issues Logically, there are three plausible options when Indigenous Peoples exercise their rights to self-determination: to accept assimilation, to maintain self-government, and to seek independence. A series of alien rulers had in the past sought at all costs to assimilate Plains Indigenes in western Taiwan, whose descendants are now almost inextinguishable from non-indigenes. Only those Indigenous Peoples who have bee geographically segregated in central mountain areas and eastern Taiwan are lucky enough to retain their cultural identities. Enlightened by the spirit of multiculturalism, more and more Indigenous Peoples are proud to express their distinguished characteristics. Nonetheless, indigenous are still divided over the rationality of upholding self-governments (Fig. 4).

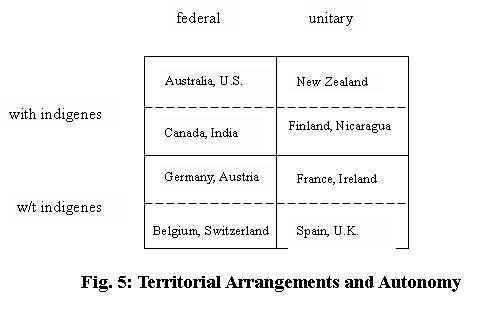

While some, for fear of discrimination, suspect the wisdom to resist further assimilation, some more, judging from the fact that non-indigenous peoples have only exploitation on their minds, economic development and social welfare assured by the government are the only guarantee for progress. In their view, therefore, the abstract principle of self-determination and the remote goal of self-rule are nothing but futile illusions. On the extreme of the spectrum, few indigenous elites have claimed that only political independence can lead to authentic salvation, even though no serious effort has been made to promote its materialization. As a result, self-government turns out to be a pragmatic compromise: while reserving their right for claiming independence, indigenous leaders would see how the government is willing to prevent indigenous governments from being empty shells. Meanwhile, it is believed that guarded by the three-layered protection from the Indigenous Basic Law, the proposed chapter on Indigenous Peoples for the proposed new Constitution (Shih, 2006),[4] and a similar one for the Bill of Rights as pledged by President Chen, indigenous self-rule may enjoy a better fate. However, since there is no guarantee that the latter two would be eventually passed by the opposition-dominated Legislature, they are drafted to include as many indigenous rights as possible stipulated in the United Nations Draft Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 1995.[5] Of course, many doubts and reservations have been raised within and without the Council of Indigenous Peoples, which is in charge of the two bills. In terms of technical feasibility, there is some disagreement over whether a federal system for central government is the only territorial arrangement compatible to indigenous self-rule. However, experiments from countries with and without indigenous peoples have show that unitary systems may equally serve the purpose of autonomy well (Fig. 5), as the case of Nicaragua has illustrated.

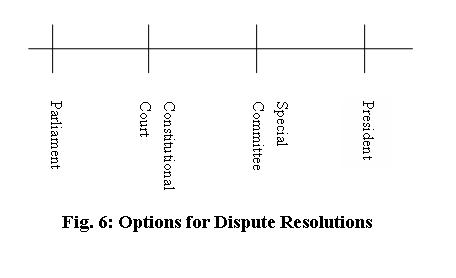

There are also concerns over which body is going to arbitrate between indigenous self-governments and central/local governments when disputes arise. Without any precedent, four options have been suggested: the Parliament, the Constitutional, a special committee, and the President. Since indigenous MP’s constitute less than 5% of the Parliament, it is doubtful how this mechanism, brought into being under the principle of one-man-one-vote, would be in any position to defend indigenous rights, unless a parliamentary committee where indigenous MP’s dominate is created. While the Constitutional Court seems an impartial branch of the central government, it is still precarious to leave the future of Indigenous Peoples in the hand of an organ where no indigenous judge would be presiding over the case in the ten to twenty years. There are suggestions that some kind of special committee is designed under the President, or the President is responsible to resolve disputes (Fig. 6). Nonetheless, it is uncertain whether the President would consider himself/herself as the head of state mandated by the dominant non-indigenes only, or as a dispassionate arbitrator supported by the Indigenous Peoples as well. In the end, there is no answer for the following challenge: “If the relationship between the Indigenous Peoples and the state is considered as “partnership,” shouldn’t there be an outside third party to play the role of arbitrator?” This question deserves further considerations not only among the Indigenous Peoples but also between elites from indigenous and non-indigenous sectors.

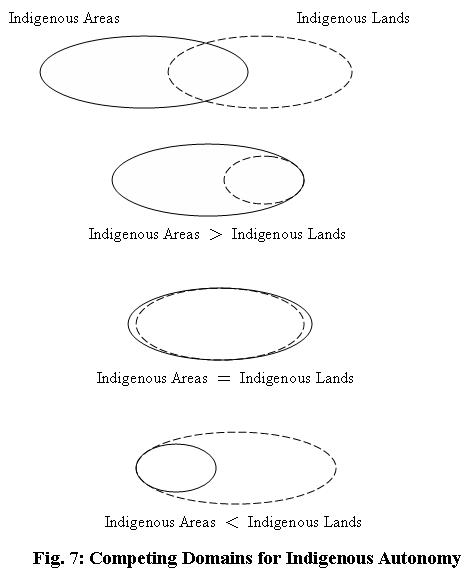

Eventually, the final battleground is found in the appropriation of lands for indigenous self-governments. Under Article 2 of the Indigenous Basic Law, two relevant terms are defined: “Indigenous Areas” means those areas traditionally occupied by Indigenous Peoples and sanctioned by the Executive, and “Indigenous Lands” includes traditional lands occupied by the Indigenous Peoples and current lands nominally reserved for them. Since these two are conceptually distinct, we may delineate their possible relationships in terms of Venn Diagrams (Fig. 7).

Since the end of World War II, the government has confined the so-called “Indigenous Areas” into 55 townships, among which 30 are designated as “Mountain Indigenous Townships,” and 25 “Plains Indigenous Townships.” For most ministries and agencies concerned, especially the Bureau of Forest Services and, to a less degree, the State Park Authorities, this administrative arrangement is definite without any doubt. In other words, the “Indigenous Lands” lie within the limits of the “Indigenous Areas.” This defensive interpretation makes them anxious calculate how many lands they would be forced to release to Indigenous Peoples in case any self-governments come into existence. In their contemplation, the best strategy is to retain the ongoing system of token monetary compensation without their jurisdictions over indigenous land being taken away. In the meantime, they also keep close eyes on the proposed mechanisms for co-management on indigenous lands confiscated for public utilities. However, for the Council of Indigenous Peoples, which is currently undertaking surveys on traditional lands that had once been utilized by the Indigenous Peoples in the past, there is no reason why the boundaries of these old administrative units cannot be subject to any adjustments. According to the maps of traditional territories drawn according to oral narratives so far, some Indigenous Peoples have claimed that their tribal lands extend beyond the highly restricted “Indigenous Areas.” Therefore, even though the so-called “Indigenous Lands” stipulated in the Indigenous Basic Law have not been designated, they are expected to cover the whole “Indigenous Areas.” Theoretically speaking, the whole island used to belong the Indigenous Peoples. Nonetheless, it is not clear whether they are descendants of those assimilated Plaines Indigenes. Unless the 12 Indigenous Peoples forge formal alliance with Plaines Indigenes, claims over the land beyond the “Indigenous Areas” will be strongly resisted. In the short time, one feasible compromise is to limit land claims to the “Indigenous Areas,” in the hope that the whole officially designated indigenous reserved lands be handed over to indigenous self-governments.

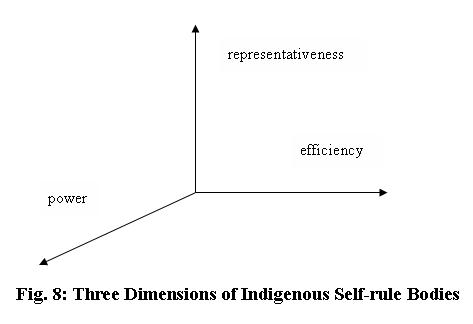

Visions For an indigenous self-government to work effectively with an eye to protect indigenous rights, three aspects are crucial for meaningful institutional designs: authority, efficiency, and representativeness (Fig. 8). First of all, to be truly autonomous, political authority of the indigenous government must find its place in the Constitution. Otherwise, its uniqueness as a manifestation of inherent indigenous rights would run the risk of being compromised, if not nullified, by a legislature dominated by non-indigenes.

Secondly, there are also debates over whether there shall be one indigenous government only, one self-government for each Indigenous People, or as many tribal governments as possible. Since not all Indigenous Peoples are opt for self-rule, at least in the short run, a pan-indigenous self-government, even a confederation in the loosest sense, seems impractical. On the other hand, tribal governments appear to be the best model to express grassroots participation for direct democracy, caution should be made against low economy of scale. Thirdly, there have been conflicting views over what institutional arrangements to represent the Indigenous Peoples (Fig. 9). It appears that the goal of sufficient representation may at times contradict that of efficiency. Ideally, there would be one tribal council for each tribe with and without self-government. As a result, depending on the definition of tribe, it is estimated that there would be roughly 250 tribal councils. While retaining their autonomy, these tribal councils are expected to forge some forms of coalition along cultural lines in order to bargain with the government. Depending on different patterns of tribal organizations, whether scattered or concentrated, these processes of internal integration warrant some cautious procedures.

There have some suggestions that a second chamber be established in the national legislative body. This amounts to bestow a right of minority veto to the Indigenous Peoples. It is not clear if the “mainstream” of society is ready to embrace this Lijphartian consociational mechanism. Finally, indigenous leaders have persistently put forward to the formation of a pan-indigenous assembly fashioned after the Assembly of First Nations in Canada. It is hoped that this representative body may select a grand chief who is co-equal with the President so that the idea of “nation to nation” relation may be formally embodied.

Conclusions The author was fortune enough to deliver a speech on indigenes’ constitutional rights at the first assembly of indigenous leaders in history at Taichung, Taiwan, on June 28, 2006. At this historical occasion, these tribal leaders expressed their endorsement for the draft indigenous chapter of the new constitution. They also declared their determination to take back their traditional lands. So far, at least one Indigenous Assembly, formed by the Thao People, a people with a population less than 1,000, has been recognized by the government, which has agreed to return a 150-acreage land to this smallest people. Still, there are not without any setbacks. For instance, in the aftermath of the downsize of the Parliament after constitutional amendments in 2005, guaranteed indigenous seats will be reduced from 8 to 6 in the future. Also, there have been subtle restrictions on indigenous affirmative actions. They are still strangers on their own lands.

References Mona, Awi. 2007. “International Perspective on the Constitutionality of Indigenous Peoples’ Rights.” Taiwan International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 85-139. Shih, Cheng-Feng, 2007. “Taiwanese National Identity: In Search of Statehood.” Paper presented at Prepared for the International Studies Association 48th Annual Convention, Chicago, February 28–March 3 (http://mail.tku.edu.tw/cfshih/seminar/20070228.htm). Shih, Cheng-Feng. 2006. “The Special Chapter for the Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan New Constitution” (http://www.taiwanthinktank.org/ttt/attachment/article_544_attach2. pdf). Shih, Cheng-Feng, 1999. “Legal Status of the Indigenous Peoples in Taiwan.” Paper presented at the International Symposium on the Rights of the Indigenous Peoples, Taipei, Taiwan, June 18-20 (http://www.taiwanfirstnations.org/legal.html). Shih, Cheng-Feng, 1995. “Ethnic Differentiation in Taiwan.” Journal of Law and Political Science (法政學報), No. 4, pp. 89-111 (http://www.wufi.org.tw/eng/taiethni.htm). Simon, Scott. 2006. “Taiwan’s Indigenized Constitution: What Place for Aboriginal Formosa?” Taiwan International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 251-70. * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the International Peace Research Association Biannual Conference “Patters of Conflict Paths to Peace,” University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, June 29-July 3, 2006. ** The author is co-convenor of the Indigenous Working Group for Promoting New Constitution, Council for Indigenous Peoples. He also serves as chairman of the Administrative Sub-committee of the Working Group for Enacting the Indigenous Basic Law, Council for Indigenous Peoples. His articles in English may be found at http://mail.tku.edu.tw/cfshih/default2.htm. For correspondence: cfshih@mail.tku.edu.tw. [1] They are the Atayal, Saisiyat, Bunun, Tsou, Rukai, Paiwan, Puyuma, Amis, Yami, Thao, Kavalan, Truku, and the latest recognized Sakilaya.. [2] For a general treatment of the settlement of Taiwan from an indigenous perspective, see Mona (2007). [3] The members include the premier, 11 ministers, 23 indigenous representatives, and 5 experts and scholars. The author is honored to be included in the last categories. [4] For an unofficial English translation of the text, see Simon (2006). [5] For the text of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples passed by the UN General Assembly on September 13th, 2007, see http://www.ohchr.org/english/issues/indigenous/docs/draftdeclaration. pdf.

|