|

原住民族非政府組織與聯合國原住民族權利宣言* |

||

|

施正鋒 淡江大學公共行政學系暨公共政策研究所教授 |

||

|

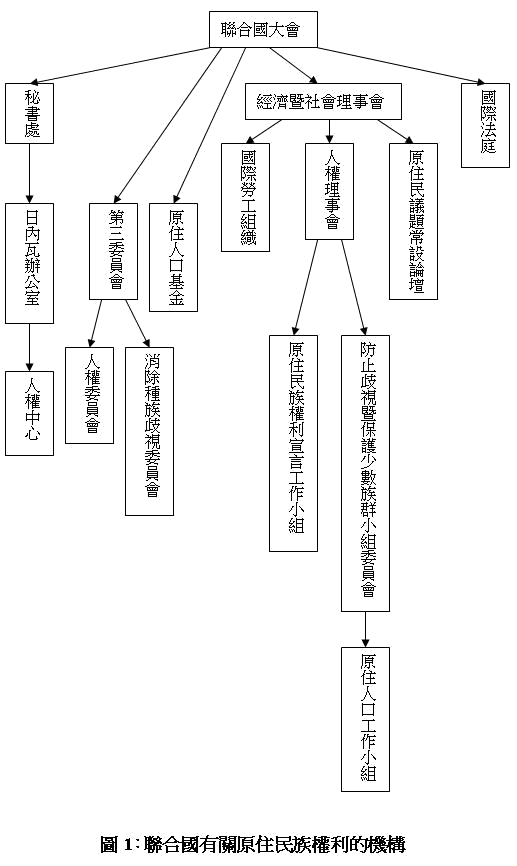

前言 回顧聯合國「原住人口工作小組[1]」在1982年成立,除了關心各國對於原住民族權利的保障[2],並從1985年起開始草擬有關原住民族權利的宣言,在1994年將草案上呈「防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會[3]」。該小組委員會經過審查,在1995年將宣言草案上呈「人權理事會[4]」;接下來,該理事會成立了一個工作小組[5],終於在2006年完成漫長的審查,再往上送「經濟暨社會理事會[6]」,於同年完成定稿;最後,聯合國大會在今年(2007)9月13日正式通過『原住民族權利宣言[7]』。(見圖1) 在這裡,我們先要回顧世界原住民族運動的發展,尤其是國際性原住民族非政府組織的出現。接著,我們要描述原住民族非政府組織在聯合國的人權體系下的奮鬥,如何促成原住人口工作小組、以及『原住民族權利宣言』。再來,我們要藉著兩個重要國際性原住民族非政府組織,觀察原住民族權利保障的推動。

世界原住民族運動 早在19世紀末期、20世紀初,紐西蘭毛利人就曾經幾次組團到倫敦(1882、1884、1914、1924),希望能當面向英國國王陳情;前兩次徒勞無功,第三獲得喬治五世接見,而第四次則無法覲見,認為被當作是乞丐看待(Sanders, 1980)。在20世紀初期,英屬哥倫比亞的 Nishga酋長兩度組團覲見英王愛德華七世(1906、1909),最後,陳情書還是被退回給加拿大政府(Sanders, 1980)。 在1920年代[8],加拿大Iroquois原住民的領袖Levi General Deskaheh就幾度前往位於日內瓦的國際聯盟[9]陳情,雖然獲的一些國家代表的支持,卻未能如願進入會場,只好透過非正式的演講來告洋狀(Sanders, 1994: 4; Niezen, 2003: 30-34)。在聯合國籌備會議召開之際,一個Iroquois代表團千里迢迢來到舊金山請願,卻未能獲得發言的許可;在1950年代,總部設於加拿大英屬哥倫比亞省的「北美印地安兄弟會[10]」組團到紐約請願,當時主管聯合國人權部門的加拿大人John Humphry勸他還是回到「自己的」國家,去跟政府打交道(Sanders, 1994: 5;

1980)。 在1960年代[11],一些關心南美洲原住民族文化滅種的團體逐漸出現,譬如位於哥本哈根的「國際原住民事務工作小組[12]」、以及位於倫敦的「國際生存組織[13]」;在1971年,「普世教協[14]」所屬的「對抗種族主義計畫[15]」召開一場有關南美的研討會[16],通過去殖民先聲的『巴貝多宣言[17]』(Sanders, 1994: 6-7)。另外,在國際原住民事務工作小組的幫助下,來自斯坎地那維亞三國的沙米人、格林蘭及加拿大的依努伊人、加拿大的Dene印地安人,在丹麥的上議院召開「極地民族會議[18]」(Jull, 1998)。 在1975年,兩個國際原住民族組織的先驅成立,也就是位於加拿大的「世界原住民族理事會[19]」、以及總部設在美國的「國際印地安條約理事會[20]」。世界原住民族理事會分別在1977年、以及1981年於瑞典、以及澳洲召開會議,於前者通過『人權宣言』,在後者探討澳洲政府與原住民族簽訂條約的可能;國際印地安條約理事會則把重點放在對聯合國的遊說工作,並主導在1977年、以及1981年於日內瓦召開的原住民族非政府組織會議(Sanders, 1994: 7)。 由於國際原住民事務工作小組的Helge Kleivan與當時的挪威外交部長Thorvald Stoltenberg熟識,挪威開始把國際原住民族組織當作外援的對象,包括國際原住民事務工作小組、以及世界原住民族理事會;挪威甚至於呼籲北歐國家在國際舞台支持原住民族議題,譬如說,荷蘭變成原住民族的支持者,並在1980年於鹿特丹召開「第四次羅素大審[21]」,公佈『原住民族宣言[22]』關心美洲印地安人的權利(Sanders, 1994: 7)。其實,聯合國在1982年設立原住人口工作小組,就是由聯合國人權中心的荷蘭籍主任Theo Van Boven主導[23],並在北歐國家的呼應下大功告成(Sanders, 1994: 7)。 自從1982年起,原住民族開始積極參與聯合國所召開的會議。譬如在1992年於里約熱內盧舉行的「聯合國環境暨發展會議[24]」;當時通過的『里約熱內盧環境暨發展宣言[25]』,陳述原住民族對於環境管理與發展的重要角色,同時時間通過『二十一世紀議程[26]』,也說明原住民族如何參與自然環境與永續發展。在1993年於維也納召開的「聯合國世界人權會議[27]」,大會通過的『維也納宣言暨行動綱領[28]』,特別建議聯合國有必要成立一個原住民族常設論壇。 非政府組織在聯合國 由於聯合國是一個國際組織[29],顧名思義,是國家與國家的競技場,因此,並不是非政府組織[30]可以任意馳騁發揮的地方;不要說安全理事會[31]為常任理事國所把持,聯合國大會也是限定國家所派出的代表(也就是駐聯合國大使)才有發言權,而人權理事會也是各國進行政治角力的地方[32]。不過,防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會[33]卻是自始歡迎非政府組織積極參與討論,或許因為被定為人權理事會的智庫,因此,鼓勵非政府組織與小組委員會的專家、以及各國代表進行對話。 大體而言,除了防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會允許非政府組織全程參加,非政府組織如果要參與聯合國的正式會議[34](包括人權理事會),必須具有經濟暨社會理事會的諮詢資格[35](consultative status)。非政府組織在防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會的活動,主要集中在人權侵犯的關心;他們的做法大致是在幕後進行遊說工作,譬如向小組委員會的專家散發決議的草案、投訴人權侵害的事件、建議人權保障的原則或標準、或是提供專業技術與實地經驗(Eide, 1992: 259-61; Alfredsson & Ferrer, n.d.: 4-5, 12-15, 25-26, 27-31, 41)。 不過,非政府組織對於推動原住民族權利保障的最大貢獻,就是促成防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會成立原住人口工作小組。在1960年代中期,一名在聯合國人權中心[36]就職的瓜地馬拉籍律師Augusto Willemsen-Diaz,在進行種族歧視的關注之際,首度提出對於原住民族人權的關心,在1970年的一份有關種族歧視的研究報告上,終於有建議另外研究原住民的文字,這可以說是原住民族人權首度引起聯合國的注意;防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會在1971年委任José R. Martínez

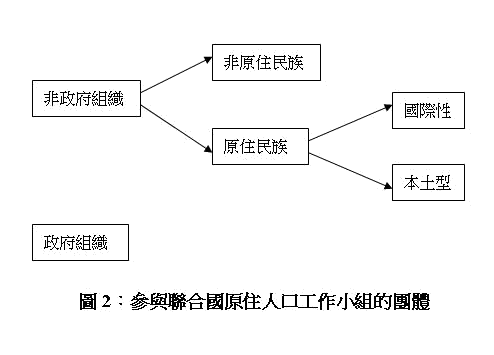

Cobo[37],從事原住人口其是問題的研究;不過,這份報告一直要到1983年才完成,原住人口工作小組已經搶先一步成立了(Sanders, 1994: 6)。 聯合國在1978年於日內瓦召開「世界(反)種族主義會議[38]」,除了說挪威把沙米原住民(Sami)納入代表團,會議聲明也特別提及原住民族的權利;聯合國於1981年於尼加拉瓜召開反種族歧視區域會議,把重點放在原住民族(Sanders, 1994: 7)。不過,真正促成防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會成立原住人口工作小組的,是國際印地安條約理事會促成「非政府組織人權特別委員會[39]」,分別在1977年[40]、以及1981年[41],於日內瓦聯合國大樓召開原住民族非政府組織會議。防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會終於在1981年提議設置原住人口工作小組,並在1982年先後獲得人權理事會、以及經濟暨社會理事會的決議支持[42]。 原住人口工作小組每年在日內瓦召開年會,被當作是防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會的會前會。由於原住人口工作小組開放給所有的原住民參加[43],尤其是鼓勵非政府組織提供資訊,自然而然地就提升原住民族組織在國際舞台的能見度:一方面,工作小組會在會前舉辦訓練課程,幫助原住民了解國際人權保障的體系,另一方面,原住民族組織也會先開策略會議,以便協調彼此所關注的重大議題;相對之下,除了少數政府會訓令其代表與原住民族代表進行建設性對話,大部分國家的代表在工作小組上會選擇採取低調的方式,反而看起來是觀察員一般(Eide, 1992: 237)。 原住民族非政府組織的努力 關心原住民族權利的非政府組織,可以分為原住民族、以及非原住民族[44]兩大類,而前者又分為國際性、以及本土[45]的兩種(Rodley, n.d.)(見圖2)。在1997年,有15個原住民族組織具有經濟暨社會理事會的諮詢資格(OHCHR, n.d.)[46]。最特別的是澳洲原來的「原住民暨托雷斯海峽群島人委員會[47]」,雖然在體制上是隸屬移民、多元文化暨原住民事務部,而且每年也有相當可觀的預算可以執行,不過,由於其委員完全由全國各地的35個區域理事會選出來,因此,又有一點民族議會的性質,或許因為這樣,才會被認為具有本土型原住民非政府組織的本質。。我們接下來要介紹的是世界原住民族理事會、以及國際印地安條約理事會,領導世界原住民運動,算是真正的國際性原住民族非政府組織[48]。

世界原住民族理事會的創辦人是George Manuel(1929-89),他在1972年擔任加拿大參加聯合國環境會議代表團的顧問,因此有機會訪問瑞典的沙米人[49];隨後,他相繼拜訪位於日內瓦的國際勞工組織、普世教協,位於哥本哈根的國際原住民事務工作小組,以及位於倫敦的國際生存組織、「反奴役協會[50]」,並宣布舉辦世界級原住民族大會的意圖(Sanders, 1980)。Manuel獲得加拿大「全國印地安兄弟會[51]」的支持,同時,也得到教會組織的贊助,尤其是普世教協,終於在1975年正式成立世界原住民族理事會(Sanders, 1980)。 世界原住民族理事會分別在1977年、以及1981年於瑞典、以及澳洲召開會議,探討如何透過條約的簽訂來保障原住民族的權利,特別是土地權(Sanders, 1980; WCIP,

1981; Hoggan, 1981; Ryser,

1988)。譬如說,世界原住民族理事會在1970年代末期,開始譴責國際勞工組織在1957年通過的『原住暨部落人口條約』未能諮詢原住民族、以及採取整合的立場;國際勞工組織在1986年從善如流,邀請世界原住民族理事會、以及國際生存組織參加討論,終於有1989年的『原住暨部落民族條約』(Laenui, 1993)。 國際印地安條約理事會是在1974年由Cherokee雕塑家Jimmie Durham所推動,在成立之際,有5,000多名來自98個原住民族的代表與會,並在1977年成為第一個取得經濟暨社會理事會諮詢資格的國際性原住民族組織(IITC, n.d.)。Durham早就參與美國印地安人運動,包括「美國印地安運動[52]」的成立;在1960末期、及1970年代初期,Durham旅居日內瓦(夫人任職於普世教協),躬逢民族解放運動風起雲湧,因緣際會認識非洲前來的反殖民領導者,深受啟發,並成功說服一些重要的國際非政府組織在日內瓦舉辦會議,讓世人了解美洲印地安人的命運;他隨後回國,說服美國印地安運動朝國際舞台發展,終於有國際印地安條約理事會出現(Dunbar-Ortiz,

2006)。對於世界原住民運動,國際印地安條約理事會的最大貢獻,就是促成聯合國非政府組織人權特別委員會在1977年、以及1981年於日內瓦召開原住民族非政府組織會議,進而有原住人口工作小組在次年成立。 結語 從1977年在日內瓦召開原住民族非政府組織會議、原住人口工作小組在1982年成立、到聯合國大會於今年通過『原住民族權利宣言』,剛好經歷30年的歷程,這是世界原住民族運動的功勞;不過,由宣言到提升為規約,恐怕還要20年以上的努力。原住民族非政府組織經過17年的討論,終於在1994 年於日內瓦通過原住民族版的『原住民族權利國際規約[53]』,希望能獲得世界各地的原住民族簽署(Ryser, 1994),這是一種標竿,用來鞭策聯合國的『原住民族權利宣言』。在民進黨政府於2000年執政以來,原住民族運動被全盤吸納,很難對於世界原住民族權利保障運動有所貢獻。 附錄1:具有經濟暨社會理事會諮詢資格的原住民族組織* Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Commission Associación Kunas

Unidos por Nabguana Four Directions

Council Grand Council of the

Crees (of Quebec) Indian Council of

South America Indian Law Resource

Centre Indigenous World

Association International Indian

Treaty Council International

Organization of Indigenous Resource Development Inuit Circumpolar

Conference National Aboriginal

and Islander Legal Services Secretariat National Indian

Youth Council Saami Council Sejekto Cultural

Association of Costa Rica World Council of

International Peoples 附錄2:相關國際規約、宣言 ILO Convention 107: Convention Concerning the Protection and

Integration of Indigenous and Other Tribal and Semi-tribal Populations in

Independent Countries, 1957 (http:// www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?C107). International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of

Racial Discrimination, 1965

(http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/d_icerd.htm). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966 (http://www.unhchr.ch/html/

menu3/b/a_ccpr.htm). Declaration of Barbados, 1971 (http://www.nativeweb.org/papers/statements/state/

barbados1.php). Declaration on Human Rights, 1977 (http://www.cwis.org/fwdp/International/

wcip_dec.txt). Declaration of Indigenous Peoples, 1980 (Declaration of the

Fourth Russell Tribunal) (http://www.cwis.org/fwdp/International/russell.txt) ILO Convention 169: Convention Concerning Indigenous and Tribal

Peoples in Independent Countries, 1989 (http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/cgi-lex/convde.pl?C169). Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, 1992 (http://www.unep.org/Documents.

Multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=78&ArticleID=1163). Agenda 21, 1992 (http://www.unep.org/Documents.Multilingual/Default.asp?DocumentID=

52). Vienna

Declaration and Programme of Action, 1993 (http://www.unhchr.ch/

huridocda/huridoca.nsf/(Symbol)/A.CONF.157.23.En?OpenDocument). International

Covenant on the Rights of Indigenous Nations, 1994 (http://www.cwis.

org/icrin-94.htm)

參考文獻 Alfredsson, Gudmundur, and Erika Ferrer.

2004. “Minority Rights: A Guide to United nations Procedures and

Institutions.” London: Minority Rights Group International (www.minorityrights.org/download.php?id=52). American Indian Law Alliance (AILA). n.d.

“International Advocacy: A Brief Summary of the International Advocacy

Mechanisms of Indigenous Peoples at the United Nations.”

(http://www.ailanyc.org/UN%20OVERVIEW.pdf) Anaya, S. James. 2004. Indigenous Peoples in

International Law, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University

Press. Chartier,

Clem. 1981. “Fourth Russell Tribunal: On the Rights of the

Indians of the Americas.” Saskatchewan Indian, Vol. 11, Nos.

1-2, pp. 7-8 (http://www.sicc.sk.ca/

saskindian/a81jan07.htm). Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. 2006. “What Brought Evo Morales to Power? The Role of the International

Indigenous Movement and What the Left Is Missing.” (http://

mrzine.monthlyreview.org/dunbarortiz060206.html) Eide, Asbjorn. 1992. “The Sub-Commission on

Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities,” in Philip Alston,

ed. The United Nations and Human Rights: A Critical Appraisal, pp.

211-64. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Editor’s Report. 2001. “Twenty-five Years of

Indigenous at the United Nations.” Indian Country Today, August

21 (http://www.indiancountry.com/content.cfm?

id=137). Hoggan, Debra M.

1981. “Land Rights of the Indigenous Peoples, International Agreements

and Treaties, Land Reform and Systems of Tenure.” (http://www. cwis.org/fwdp/International/lndright.txt) International Indian Treaty Council (IITC). n.d. “About Us: IITC Program Priorities.” (http://www.treatycouncil.org/about.htm) Jull, Peter. 1999. “Indigenous Internationalism:

What Should We Do Next?” (http://www.

yukoncollege.yk.ca/~agraham/nost202/jullart1.htm) Jull, Peter. 1998. “’First World’ Indigenous

Internationalism after Twenty-Five Years.” Indigenous Law Bulletin,

Vol. 4, No. 9 (http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/journals/ILB/1998/

15.html). Jull, Peter. 1991. “Internationalism, Indigenous

Peoples an Sustainable Development,” in D. Lawrence, and Tim Cansfield-Smith, eds. Sustainable Development for

Traditional Inhabitants of the Torres Straits Region, pp. 427-39.

Townsville: Great Barrier Reef Marine park Authority (http://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/

0019/4168/ ws016_paper_35.pdf). Laenui, Poka. 1993. “A Primer on International

Activities as Related to the Quest for Hawaiian Sovereignty.”

(http://www.opihi.com/sovereignty/internat_law.txt). Larson, Erik. n.d.

“Regulatory Rights: Emergent Indigenous Rights as a Locus of Global

Regulation.” (http://www.lawandsocietysummerinstitutes.org/rights_reg/

ch_7.pdf) Niezen, Ronald.

2003. The Origins of Indigenism.

Berkeley: University of California Prss. Office of the High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR). n.d. “Fact Sheet, No. 9 (Rev. 1): The Rights of

Indigenous Peoples.” (http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu6/2/fs9. htm) Pritchard, Sarah. 1998. “Working Group on Indigenous

Populations: Mandate, Standard-setting Activities and Future Perspectives,”

in Sarah Prichard, ed. Indigenous Peoples, the United Nations and Human

Rights, pp. 40-64. London: Zed Books. Rodley, Nigel S. n.d. “Human Rights NGOs: Rights and Obligation

(Present Status and Perspectives).” (http://www.uu.nl/uupublish/content-cln/04Rodley.pdf) Ryser,

Rudolph C. 1994. “Evolving New International Laws from the Forth

World: The Covenant on the Rights of Indigenous Nations.”

(http://www.cwis.org/ icrinsum.html) Ryser, Rudolph C.

1988. “Statement in reference to the Study on the Significance of

Indigenous Treaties.” (http://www.cwis.org/fwdp/International/uncwis88.txt) Sanders, Douglas. 1994. “Developing a Modern

International Law on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.” Report to the Royal

Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (http://www.ubcic.bc.ca/files/PDF/Developing.pdf). Sanders, Douglas. 1980. “The Formation of the World

Council of Indigenous Peoples.”

(http://www.halcyon.com/pub/FWDP/International/wcipinfo.txt) Venne, Sharon

Helen. 1998. Our Elders Understand Our Rights: Evolving

International Law Regarding Indigenous Rights. Penticton, B.C.: Theytus Books. Washinawatoj,

Ingrid. 2003. “Working toward an Indigenous Model.” Indian

Country Today, May 14 (http://www.indiancountry.com/content.cfm?id=

1052919902). Willetts,

Peter. 1996. “Consultative Status for NGOs at the UN.” (http://www.staff.city.ac.

uk/p.willetts/NGOS/CONSSTAT.HTM) World Council of Indigenous Peoples (WCIP). 1981.

“The Need for International Conventions.” (http://www.cwis.org/fwdp/International/intconv.txt) 陳麗瑛。2003。〈台灣參與聯合國具諮詢地位之INGO之策略〉《新世紀智庫論壇》23期,頁32-53。

* 發表於台灣基督長老教會總會原住民宣教委員會主辦「聯合國原住民族權利宣言研討會」,台北,2007/12/8。 [1] Working Group on

Indigenous Populations,簡稱WGIP。見Prichard(1998)的研究。 [2] 有關於國際法對於原住民族權利保障的發展,見Venne(1998)、以及Anaya(2004)。見Larson(n.d.) 有關於原住民族權利納入國際法人權保障,也就是所謂的「體制化」(institutionalization)。 [3] Sub-committee on

Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities,於1947年設立。1999年改名為Sub-committee on the Promotion

of Human Rights;可能面對裁撤的命運。 [4] 原名為Commission on Human Rights(簡稱CHR),於1946年設立;在2006年被Human Rights Council所取代。我們之所以翻譯為人權理事會,是因為在聯合國大會之下的「第三委員會」(Third Committee), 另外有「人權委員會」(Human Rights

Committee,簡稱為HRC)。前者是所謂的「憲章機構」(charter body), 隸屬經濟暨社會理事會(Economic and Social

Council,簡稱ECOSOC);後者為「條約機構」(treaty body),負責監督『國際公民暨政治權規約』(International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966)的執行。 [5] Open-Ended

Inter-Sessional Working Group on the Draft Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples,簡稱為IWG。 [6] 經濟暨社會理事會有54名國家代表。經濟暨社會理事會在2000年成立「原住民議題常設論壇」(Permanent Forum on

Indigenous Issues,簡稱為PFII),作為諮詢機構。 [7] United Nations

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007。 [8] 根據另一種說法,他早在1917年就首度前往日內瓦(AILA, n.d.:

4)。 [9] League of Nations。 [10] North American

Indian Brotherhood。 [11] 其實,聯合國的周邊組織國際勞工組織(International

Labour Organization)在1920年代就開始關心原住民勞工被剝削的問題(Sander,

1994: 4);在1957年、以及1989年,國際勞工組織先後通過『原住暨部落人口條約』(ILO

Convention 107: Convention Concerning the Protection and Integration of

Indigenous and Other Tribal and Semi-tribal Populations in Independent

Countries, 1957)、以及『原住暨部落民族條約』(ILO Convention

169: Convention Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent

Countries, 1989)。 [12] International Work

Group for Indigenous Affairs,簡寫為IWGIA。 [13] Survival

International。 [14] World Council of

Churches。 [15] Program to Combat

Racism。 [16] Symposium on

Inter-Ethnic Conflict in South America。 [17] Declaration of

Barbados, 1971。 [18] Artic Peoples

Conference。 [19] World Council of

Indigenous Peoples,簡寫為WCIP。 [20] International

Indian Treaty Council,簡寫為IITC。 [21] Fourth Russell

Tribunal,見Chartier(1981)。 [22] Declaration of Indigenous Peoples, 1980,又稱為Declaration of the Fourth

Russell Tribunal。 [23] 根據(Dunbar-Ortiz, 2006),他因此得罪雷根政府而被逼下台。 [24] United Nations Conference on Environment and Development,簡稱為UNCED;又稱為「地球高峰會議」(Earth

Summit)。 [25] Rio Declaration

on Environment and Development, 1992。 [26] Agenda 21, 1992。 [27] United Nations

World Conference on Human Rights。 [28] Vienna Declaration

and Programme of Action, 1993。 [29] Intergovernmental

organization,簡寫為IGOs。 [30] Nongovernmental

organization,簡寫為NGOs。 [31] Security Council。 [32] 人權理事會每年在日內瓦召開會議六個禮拜,包含53個會員國,由經濟暨社會理事會選舉產生,由外交官代表各國;非成員國可以擔任觀察員,可以發言、卻沒有投票權(Alfredsson & Ferrer, n.d.: 27)。 [33] 防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會每年在日內瓦召開會議三個禮拜,由26名專家組成,由各國提名,經人權理事會選舉產生,任期四年(Alfredsson & Ferrer, n.d.: 30-31)。 [34] 譬如說,聯合國大會第三委員會所屬的條約機構人權委員會、或是負責監督『消除各種形式種族歧視國際公約』(International

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, 1965)執行的消除種族歧視委員會。 [35] 有關於如何向經濟暨社會理事會的非政府組織委員會(Committee on

Non-Governmental Organizations)取得這個資格,見Alfredsson與Ferrer,(n.d.: 39)、Willetts(1996)、以及陳麗瑛(2003)。 [36] Human Rights Centre,位於日內瓦。 [37] 是小組委員會的成員,為來自厄瓜多爾的外交官(Sanders, 1994: 6)。 [38] World Conference on

Racism。 [39] Special NGO

Committee on Human Rights(位於日內瓦)之下的NGO Sub-Committee on

Racism, Racial Discrimination, Apartheid, and Colonialism(Dunbar-Ortiz, 2006)。 [40] International NGO

Conference on Discrimination Against the Indians of the Americas。總共有來自15個國家、60個原住民族(包括Cheyenne、Mapuche、Cree、Lakota、Haudenosaunee、Mayan、以及Ojibway)的165名代表與會(Editor’s Report, 2001; AILA, n.d.: 4; Washinawatok, 2003)。美國總統卡特指派兩名原住民運動人士Kirk Kickingbird、以及Shirley

Hill Witt加入代表團(Dunbar-Ortiz,

2006)。 [41] International NGO

Conference on Indigenous Peoples and the Land。也有150多人參加;不過由於美國總統雷根呼籲各國杯葛,因此,政府代表減少,西方國家只有挪威派出政府代表(Dunbar-Ortiz,

2006)。 [42] 由5名來自五大洲的專家組成,這些人本身也是防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會的委員。 [43] 聯合國大會在1985年設置「原住人口基金」(Voluntary Fund for Indigenous

Populations),每年可以補助40名原住民族代表與會(OHCHR, n.d.)。在1996年,超過800名原住民族代表與會(Editor’s Report, 2001)。 [44] 譬如說普世教協、國際生存組織、 [45] 譬如說加拿大的Grand Council of the Crees (of Quebec)。 [46] 名單見附錄1。參見Sanders(1994)的批判。 [47] Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander Commission,簡寫為ATSIC;在1995年由Bob Hawke的工黨政府成立,在2005年被John Howard的自由黨/國家黨聯合政府廢止。不過,根據Sanders(1994: 13-14)的說法,該會並沒有資格申請。 [48] 成立於1997年的「依努伊極地會議」(Inuit Circumpolar Conference),由阿拉斯加、加拿大、格林蘭、以及俄羅斯的依努伊人組成,也可以算是有資格限制的國際性原住民族非政府組織(Jull, 1991, 1999)。另外,成立於1968年國際原住民事務工作小組,具有經濟暨社會理事會的諮詢資格,主要成員是專家學者、以及人權工作者;原先的關注對象是亞馬遜河流域的原住民族,現在的視野擴及全球,不過,比較像是一個智庫。 [49] 根據Jull(1998),George Manuel在1973年參加在哥本哈根召開的極地民族會議,多少啟發他召開世界原住民族會議的念頭。 [50] Anti-Slavery

Society。 [51] National Indian

Brotherhood(Assembly of First

Nations的前身),在1974年取得經濟暨社會理事會諮詢資格(世界原住民族理事會成立後,接收其資格);George Manuel擔任過三任會長(1970-76)(Sander, 1980)。 [52] American Indian

Movement。 [53] International

Covenant on the Rights of Indigenous Nations, 1994。 * OHCHR(n.d.)。 |