|

原住民族的文化權* |

||

|

施正鋒 淡江大學公共行政學系暨公共政策研究所教授 |

||

|

That the wide

diffusion of culture, and the education of humanity for justice and liberty and

peace are indispensable to the dignity of man and constitute a sacred duty

which all the nations must fulfil in a spirit of mutual assistance and

concern; That a peace based

exclusively upon the political and economic arrangements of governments would

not be a peace which could secure the unanimous, lasting and sincere support

of the peoples of the world, and that the peace must therefore be founded, if

it is not to fail, upon the intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind. 聯合國教科文組織憲章[1](1945)前言 壹、前言 就字面來看,所謂的「原住民族的文化權」(indigenous cultural

rights),是「原住民族」(indigenous peoples)與「文化權」(cultural rights、right to culture)這兩個概念的結合。而所謂的「文化權」,是「文化」與「權利」的結合,簡而言之,就是少數族群保有、並發展其文化的權利(Mupaulanga-Hulston,

2002: 35)。因此,我們可以這樣說,原住民族的文化權,是指原住民族在文化層面所享有的人權。 Karel

Vasak 根據人權發展的先後,有所謂的「人權三代論」(Baehr, 1999: 6):(一)屬於第一代人權的公民權、以及政治權(civil、political rights),(二)屬於第二代人權的經濟權、社會權、以及文化權(economic、social、cultural rights),以及(三)屬於第三代人權的共同權[2](rights of solidarity)。那麼,乍看之下,文化權應該是屬於第二代人權的範疇,與經濟權、以及社會權為姊妹人權;然而,近年來,一般又習慣將少數族群權利[3](minority rights、minority group rights)列為三代人權,那麼,屬於原住民族權利(indigenous rights)之一的原住民族文化權,應該也可以算是這裡所謂的共同權[4]。 另一方面,Patrick Thornberry(1995: 15-16)根據權利負載者/所有者(bearer) 的身分,也將人權分為三大類:(一)所有住民的生存權、以及自由權,(二)所有國民的公民權/政治權、以及平等權/反歧視,以及(三)少數族群的認同權/文化權。前兩種權利的出發點是消極的保障,大致可以由個人的公民身分取得;而後者則是因為個人隸屬於少數族群的身分而取得[5],算是正面推動的權利(Lerner, 1991)。 如果的要實踐原住民族的文化權,特別是在法律執行、以及政策發展的層面,就必須先要有明確的定義(Wilson, 2000: 13),因此,我們接下來要問的是,究竟文化權的範圍、或是內容是甚麼?如果要回答文化權的內涵是甚麼,就必須了解文化的意義是甚麼[6]。一般而言,文化可以有「廣義的文化」(culture)、以及「狹義的文化」(Culture)兩種。根據聯合國教科文組織(UNESCO)人權組主任Janusz Symonides(Häusemann, 1994: 10)的說法[7],所謂廣義的文化(英文小寫)[8],是指「人類與自然有所不同的地方,包括社會關係、活動、知識、以及其他作為」;而狹義的文化(英文大寫),是指「人類最高的知識性成就,包括音樂、文學、藝術、以及建築」。聯合國教科文組織於1982年召開的世界文化政策會議[9],所通過了『墨西哥市文化政策宣言[10]』,對於文化作了廣義的定義: that in its widest

sense, culture may now be said to be the whole complex of distinctive

spiritual, material, intellectual and emotional features that characterize a

society or social group. It includes not only the arts and letters, but also

modes of life, the fundamental rights of the human being, value systems,

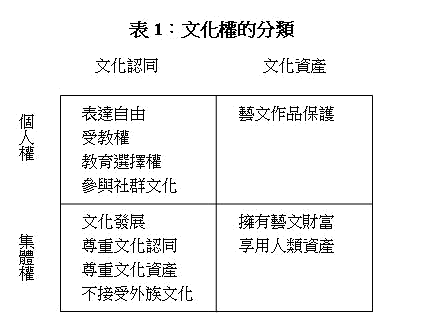

traditions and beliefs; 在這樣的脈絡下,Elsa Stamatopoulou與Joanne Bauer(2004)檢視了聯合國相關文獻,將文化分為生活方式(way of life)、藝術暨科學創造(creation)、以及物質資產(capital)三大類[11],可以說兼顧廣義、以及狹義的文化。 聯合國發展計畫[12]在『2004年人類發展報告書[13]』裡頭,提出「文化自由」的概念,兩大重點是自我認同/生活方式的選擇權、以及不能因為文化差異而被排除參與(UNDP, 2004: 14),其實就是指文化權。Stephen P. Marks(2003)提出一份清單,嘗試將文化權分為六大類[14]:文化認同及文化多元、參與文化生活、文化保存及傳播、文化合作、文化資產保護、以及文化創造者/傳遞者/傳譯者的保護。Jacob T. Levy(1997)則依文化權的性質分為八大類:免除、扶助、自治、外規(限制外人)、內規(規範成員)、承認、代表、以及象徵。Margalit與Halbertal(2004)又依據文化權實踐的程度,由淺到深,分為維持生活方式的權利、一般社會大眾的承認、以及政府出面支持;同樣地,Stamatopoulou與Bauer(2004)、以及Craven(1994)則從作為人權責任者(duty holder、duty bearer)的國家著手,從尊重(不干預)、保護(防止他者侵犯)、到實踐的進程。 比較特別的是,Lyndel V. Prott(1988: 96-87)歸納了相關國際規約、以及宣言,將文化權分為個人權(individual rights)、以及集體權[15](collective rights)兩大類:前者包括表達的自由、受教育權、父母的教育選擇權、參與社群文化權、以及藝術/文學/科學作品的保護權;後者包括文化發展權、文化認同被尊重的權利、少數族群的認同/傳統/語言/文化資產被尊重、擁有藝術/歷史/文化資產的權利、不接受外族文化的權利、以及平等擁有人類共同資產的權利。依照這份文化權的清單,Prott(1988: 87)認為文化權又可以分為文化認同、以及文化資產兩大類。我們根據個人權/集體權、以及文化認同/文化資產兩個面向,以2×2的方式,將文化權分為四大類(表1)。

在下面,我們先將從政治哲學的角度,來看文化權的正當性何在,並歸納一些反對文化權的說法。再來,我們要從相關國際規約、或是宣言著手,由聯合國、區域性國際組織、到聯合國教科文組織,找出關鍵性的條文、或是文字。接下來,在提出結論之前,我們要考察文化權如何在原住民族落實。 貳、政治理論/哲學中的文化權 在多數國家都有族群多元線線的情況下,少數族群權利的保障,被當作是實現民主、以及促進和平的先決條件;譬如歐洲理事會在1995年通過的『保障少數族群架構條約[16]』,便把對於少數族群的保護,當作是歐洲穩定、民主安全、以及和平的前提: 一個多元的真正民主社會,不只應該尊重每個少數族群其成員的文化、語言、以及宗教認同,更應該要開創妥適的條件,讓這些認同能夠表達、保存、以及發展。 大體而言,我們可以看到,國際上對於少數族群權利的保護,先是由消極的平等/反歧視著手,進而作積極的認同權/文化權確認,特別是語言權/教育權的保障;再來,少數族群權利的範圍擴及土地權(原住民族)、以及政治權/自治權;再來,我們也可以觀察到對於推動少數族群權利的趨勢,已從消極的限制歧視,逐漸發展為政府促進平等的責任(施正鋒,2004)。 Will

Kymlicka(1995)將少數族群權利[17]分為自治權、特別代表權、以及多元族群權(polyethnic rights)三大類;前者是指地域的自主性治理、以及政治參與權,而後者就是指文化權。他進一步提出三種支持保護少數族群權利的理由(頁108-23)[18]:首先是以平等(equality)作出發點,因為少數族群遭受不平等的待遇,因此,有必要透過這些權利的保障來加以匡正不公平的劣勢;再來,有些少數族群權利是基於歷史因素而來的,包括先前的主權、條約、或是其他協定;最後,多元文化本身也是一種珍貴的價值,因此,值得透過少數族群權利的保障來獲致。 Kymlicka(1989、1995)從自由主義著手[19],認為對於少數族群文化權的保障,是有助於少數族群的成員作有意義的決策,因為,文化/文化結構(cultural structure)/文化共同體(cultural community)能提供少數族群的「選擇脈絡」(context of choice),決定甚麼是自己的基本利益(essential interest)、甚麼是美好的生活(good life)、以及如何來達成。也就是說,一個少數族群如果失去了文化,就宛如喪失了自我判斷的能力[20];因此,少數族群光有自由是不夠的,國家還必須賦予他們足夠的選擇能力,因此,文化權的享有是保障其自主性的必要條件[21]。 比喻來說,如果讓我們選擇吃披薩、或是麵食,光是披薩就有各種不同的口味,而麵食也可以分為日本拉麵、義大利麵、牛肉麵、或是什錦麵;甚至於就麵條而言,除了有油麵、意麵、還是外省麵,後者還可以再細分為粗麵、中麵、細麵、甚至於刀削麵。表面上看來,上述菜單上的選項眾多,就看自己要不要吃;然而,如果就一個習慣米食的人來說,尤其是勞動工作者,第一選項當然是吃飯,那麼,這些琳琅滿目的選項,即使價格在高、營養在多,並沒有多大的意義。 儘管文化權有其規範上的支持,不過,相較於其他人權的範疇,各國政府似乎在推動上顯得意態闌珊。我們歸納各家的看法如下(Symonides,

1998; Hunt, 2000; Robbins & Stamatopoulou, 2004; Stamatopoulou &

Bauer, 2004; UNDP, 2004; Abro & Bauer, 2005; Koivunen & Marsio, 2007): (一)缺乏整合式的國際規約、或是宣言:在國際人權法的發展過程,通常是先要經過一段時間的醞釀,才會先出現沒有約束力的國際宣言;經過一段時間的推動,國際社會(聯合國、或是區域組織)有了起碼的共識,最後才會有正式的國際規約。到目前為止,有關文化權的依據,還四處散佈在不同的地方,尚難有全盤性的框架。 (二)大家對於文化的定義沒有定論,導致文化權的實踐有困難:聯合國教科文組織的對文化採用鬆散的定義,也就是「生活方式」;由於範圍過於寬廣,文化權的概念化就因此免不了含混不清,那麼,規範執行的標準化工作就很難進行。 (三)有其他比文化權更迫切的目標:對於一些人來說,文化權是一種奢侈品,只有在達到相當的發展程度,才有能力去的推動;相對地,如何讓大家滿足起碼的溫飽,對於不少政府而言,可能才是更切實際的目標。 (四)政府擔心國內違反文化權的事跡被揭露:除非這些國家本身願意面對自己內部多元族群的現實,否則,一旦簽署了相關規約,一定會被要求定期提出人權報告之際,屆時,很可能要被迫自挖瘡疤,這在國際舞台將是一件相當尷尬的事。 (五)一些政府擔心文化權的推動會影響國家團結、甚至會鼓勵分離主義:由於文化與集體認同的建構息息相關,一旦少數族群的文化獲得繁衍,可能會進一步進行政治化;即使這些少數族群未必要求分離,多數族群可能還是會有相當的威脅感。 (六)商業市場的考量:站在跨國公司的立場,一旦文化權的意識抬頭,免不了要面對文化資產如何使用的問題,到時候,不但是紛爭不斷,而且一定會造成營運成本大量提高。 (七)可能與其他人權的實踐相互牴觸:有些社會運動人士擔心,萬一文化權的推動被無限上綱,不只是可能會把認同綁死[22],也有可能會導致大家盲目地遵循傳統,甚至於侵犯到其他被一般公認的人權,特別是婦女人權的保障。 (八)認為為化權是文化帝國主義的工具:一些持文化相對主義者認為[23],如果有所謂的文化權的話,站在尊重文化差異的立場,應該是採取因地制宜的方式;而目前推動的普世人權規範,最終會消滅文化多元性。 大體而言,這些保留的看法,要不是停留在執行上的技術問題,再不就是出自非普世的考量,因此,並不敢正面大聲反對。唯一比較費心面對的,是文化相對主義的論調,基本上,這是站在國家的立場來看文化權;然而,拋開國家是否具有文化權不說,到目前為止,我們看到對少數族群文化最大的破壞,國家機器的威脅,恐怕不會小於來自國家外的文化威脅。 參、國際規約中的文化權 對於文化權的保障,最重要的國際法依據聯合國的規約、或是宣言。一些區域性的國際組織也有相關的條文,包括美洲國家組織、非洲團結組織、歐洲理事會、歐洲安全暨合作組織、以及歐洲聯盟。另外,聯合國教科文組織也有一些相關的宣言。 一、聯合國規約 聯合國大會在1948年通過『世界人權宣言[24]』,在第27條首度正式而明確地指出個人的文化權: (1) Everyone has the

right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy

the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits. (2) Everyone has the

right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from

any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author. 另外,第22條也說明文化權(以及經濟權、社會權)對於個人尊嚴、以及人格發展而言,是不可或缺的: Everyone, as a member

of society, has the right to social security and is entitled to realization,

through national effort and international co-operation and in accordance with

the organization and resources of each State, of the economic, social and

cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his

personality. 接下來,聯合國在1966年通過『國際公民暨政治權公約[25]』,在第27條間接提到少數族群的文化權: In

those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist,

persons belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in

community with the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture,

to profess and practise their own religion, or to use their own language. 在這同時通過的『國際經濟、社會、暨文化權公約[26]』,在第15條規範了國家在保護文化權上面所應盡的義務: 1. The States Parties

to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone: (a) To take part in

cultural life; (b) To enjoy the

benefits of scientific progress and its applications; (c) To benefit from

the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any

scientific, literary or artistic production of which he is the author. 2. The steps to be

taken by the States Parties to the present Covenant to achieve the full

realization of this right shall include those necessary for the conservation,

the development and the diffusion of science and culture. 3. The States Parties

to the present Covenant undertake to respect the freedom indispensable for

scientific research and creative activity. 4. The States Parties

to the present Covenant recognize the benefits to be derived from the

encouragement and development of international contacts and co-operation in

the scientific and cultural fields. 另外,聯合國在1979年通過的『消除各種婦女歧視規約[27]』(第13條)、以及在1989年『兒童權利規約[28]』(第31條),也有敦促國家保護文化權的文字。在1992年通過的『個人隸屬民族、族群、宗教、或語言性少數族群權利宣言[29]』,在第2條則具體指出少數族群的文化權: 1. Persons belonging

to national or ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities (hereinafter

referred to as persons belonging to minorities) have the right to enjoy their

own culture, to profess and practise their own religion, and to use their own

language, in private and in public, freely and without interference or any

form of discrimination. 2. Persons belonging

to minorities have the right to participate effectively in cultural,

religious, social, economic and public life. 3. Persons belonging

to minorities have the right to participate effectively in decisions on the

national and, where appropriate, regional level concerning the minority to

which they belong or the regions in which they live, in a manner not

incompatible with national legislation. 4. Persons belonging

to minorities have the right to establish and maintain their own

associations. 5. Persons belonging

to minorities have the right to establish and maintain, without any

discrimination, free and peaceful contacts with other members of their group

and with persons belonging to other minorities, as well as contacts across

frontiers with citizens of other States to whom they are related by national

or ethnic, religious or linguistic ties. 另外,該宣言在第4條則規定國家保護少數族群語言文化的義務: 2. States shall take

measures to create favourable conditions to enable persons belonging to

minorities to express their characteristics and to develop their culture,

language, religion, traditions and customs, except where specific practices

are in violation of national law and contrary to international standards. 3. States should take

appropriate measures so that, wherever possible, persons belonging to

minorities may have adequate opportunities to learn their mother tongue or to

have instruction in their mother tongue. 4. States should,

where appropriate, take measures in the field of education, in order to

encourage knowledge of the history, traditions, language and culture of the

minorities existing within their territory. Persons belonging to minorities

should have adequate opportunities to gain knowledge of the society as a

whole. 二、區域性國際組織規約 美洲國家在1948年通過『美洲人權宣言[30]』,在第13條揭櫫參與社群文化權利: Every person has the

right to take part in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts,

and to participate in the benefits that result from intellectual progress,

especially scientific discoveries. He likewise has the

right to the protection of his moral and material interests as regards his

inventions or any literary, scientific or artistic works of which he is the

author. 美洲國家組織在1988年通過的『美洲社會、經濟、暨文化權規約附加議定書[31]』,除了承認個人的文化權,同時,也規範了國家保護文化權的義務: 1. The States Parties

to this Protocol recognize the right of everyone: a. To take part in

the cultural and artistic life of the community; b. To enjoy the

benefits of scientific and technological progress; c. To benefit from the

protection of moral and material interests deriving from any scientific,

literary or artistic production of which he is the author. 2. The steps to be

taken by the States Parties to this Protocol to ensure the full exercise of

this right shall include those necessary for the conservation, development

and dissemination of science, culture and art. 3. The States Parties

to this Protocol undertake to respect the freedom indispensable for

scientific research and creative activity. 4. The States Parties

to this Protocol recognize the benefits to be derived from the encouragement

and development of international cooperation and relations in the fields of

science, arts and culture, and accordingly agree to foster greater

international cooperation in these fields. 在非洲方面,非洲團結組織在1981年通過『非洲人權憲章[32]』,也提到個人的文化參與權、以及國家保護文化權的義務: 1. Every individual

shall have the right to education. 2. Every individual

may freely, take part in the cultural life of his community. 3. The promotion and

protection of morals and traditional values recognized by the community shall

be the duty of the State. 至於歐洲聯盟,在2000年通過的『歐盟基本權利憲章[33]』,只在第22條簡短提到文化多樣性的保護: The Union shall

respect cultural, religious and linguistic diversity. 倒是在歐洲理事會方面,於1992年通過『歐洲區域或少數族群語言憲章[34]』,首度針對少數族群語言權利作詳盡的規範[35]。而在1995年通過的『保障少數族群架構條約[36]』,除了列舉少數族群的認同權、媒體權、語言權、命名權、以及教育權,並在第15條規範國家在促進文化參與權的義務: The

Parties shall create the conditions necessary for the effective participation

of persons belonging to national minorities in cultural, social and economic

life and in public affairs, in particular those affecting them. 另外,歐洲安全暨合作組織的『海牙有關少數族群教育權建議書[37]』(1996)、以及『奧斯陸有關少數族群語言權建議書暨說明[38]』(1998),對於少數族群教育權、以及語言權有相當詳細的規範。 三、聯合國教科文組織 對於文化權的保護,聯合國教科文組織當然是責無旁貸,因此,也有不少訂定標準的規約、建議書、以及宣言(UNESCO,

n.d.)。首先,在1960年通過的『反對教育歧視規約[39]』中,規定了少數族群的教育權,特別是母語的使用、以及教導: ( c ) It is

essential to recognize the right of members of national minorities to carry

on their own educational activities, including the maintenance of schools

and, depending on the educational policy of each State, the use or the

teaching of their own language, provided however: (i) That this right

is not exercised in a manner which prevents the members of these minorities

from understanding the culture and language of the community as a whole and

from participating in its activities, or which prejudices national

sovereignty; (ii) That the

standard of education is not lower than the general standard laid down or

approved by the competent authorities; and (iii) That attendance

at such schools is optional. 到目前為止,聯合國教科文組織已經通過了20多個大會宣言。在第14屆大會通過的『國際文化合作原則宣言[40]』(1966),於第一條就開宗明義提到每個人的文化發展權。在第20屆大會通過的『種族暨種族偏見宣言[41]』(1978),同樣的是在第一條宣示文化差異權、以及文化認同權: 2. All individuals

and groups have the right to be different, to consider themselves as

different and to be regarded as such. However, the diversity of life styles and

the right to be different may not, in any circumstances, serve as a pretext

for racial prejudice; they may not justify either in law or in fact any

discriminatory practice whatsoever, nor provide a ground for the policy of

apartheid, which is the extreme form of racism. 3. Identity of origin

in no way affects the fact that human beings can and may live differently,

nor does it preclude the existence of differences based on cultural,

environmental and historical diversity nor the right to maintain cultural

identity. 在第31屆大會通過的『世界文化多樣性宣言[42]』(2001),第4條說明文化多樣性的保障是對人權的尊重: The defence of

cultural diversity is an ethical imperative, inseparable from respect for

human dignity. It implies a commitment to human rights and fundamental

freedoms, in particular the rights of persons belonging to minorities and

those of indigenous peoples. No one may invoke cultural diversity to infringe

upon human rights guaranteed by international law, nor to limit their scope. 該宣言也在第 5條主張以文化權來促進文化多樣性,並列舉母語權、教育權、以及選擇參與文化生活的權利: Cultural rights are

an integral part of human rights, which are universal, indivisible and

interdependent. The flourishing of creative diversity requires the full

implementation of cultural rights as defined in Article 27 of the Universal

Declaration of Human Rights and in Articles 13 and 15 of the International

Covenant on Economic, Social and cultural Rights. All persons should therefore

be able to express themselves and to create and disseminate their work in the

language of their choice, and particularly in their mother tongue; all

persons should be entitled to quality education and training that fully

respect their cultural identity; and all persons have the right to

participate in the cultural life of their choice and conduct their own

cultural practices, subject to respect for human rights and fundamental

freedoms. 肆、原住民族文化權的實踐 國際勞工組織[43]在1957年通過『原住暨部落人口保障暨整合公約[44]』,除了一般性提到政府必須採取措施來確保原住民族的社會、經濟、及文化發展(第2條),還特別在第六部分規範了原住民族的教育權,尤其是在第23條規定政府對於住民族母語教學、以及保存的責任: 1. Children belonging

to the populations concerned shall be taught to read and write in their

mother tongue or, where this is not practicable, in the language most

commonly used by the group to which they belong. 2. Provision shall be

made for a progressive transition from the mother tongue or the vernacular

language to the national language or to one of the official languages of the

country. 3. Appropriate

measures shall, as far as possible, be taken to preserve the mother tongue or

the vernacular language. 不過,由於此規約的精神在於「整合」,譬如說,上述條款的精神是由母語的使用過渡到國家語言、或是官方語言的學習,因此,飽受抨擊。國際勞工組織從善如流,於1989年通過修正版的『原住暨部落民族公約[45]』,在第2條規範政府採取措施保護原住民族權利的,正式提到文化權的概念: 1. Governments shall

have the responsibility for developing, with the participation of the peoples

concerned, co-ordinated and systematic action to protect the rights of these

peoples and to guarantee respect for their integrity. 2. Such action shall

include measures for: (a) ensuring that

members of these peoples benefit on an equal footing from the rights and

opportunities which national laws and regulations grant to other members of

the population; (b) promoting the

full realisation of the social, economic and cultural rights of these peoples

with respect for their social and cultural identity, their customs and

traditions and their institutions; 同樣地,在第六部分規定了原住民族的教育權,包括設立自己的教育機構(第27條)、以及母語受教權(第28條)。比較特別的是在第29條,要求國家必須在歷史教科書、以及其他教材裡頭,公平而正確地提供有關原住民社會文化的介紹,以消除社會上原有的偏見: Educational measures

shall be taken among all sections of the national community, and particularly

among those that are in most direct contact with the peoples concerned, with

the object of eliminating prejudices that they may harbour in respect of

these peoples. To this end, efforts shall be made to ensure that history

textbooks and other educational materials provide a fair, accurate and

informative portrayal of the societies and cultures of these peoples. 聯合國防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會下轄的「原住人口工作小組[46]」,在1993年通過了『原住民族權利宣言草案[47]』,除了提及原住民族有免於族群滅種(ethnocide)、以及文化滅種(cultural genocide)的集體、以及個人權利(第2條),並規範政府必須有具體的作為(第7條),來保障其文化的完整性(cultural integrity): Indigenous peoples

have the collective and individual right not to be subjected to ethnocide and

cultural genocide, including prevention of and redress for: a. any action which

has the aim or effect of depriving them of their integrity as distinct

peoples, or of their cultural values or ethnic identities; b. any action which

has the aim or effect of dispossessing them of their lands, territories or

resources; c. any form of population

transfer which has the aim or effect of violating or undermining any of their

rights; d. any form of

assimilation or integration by other cultures or ways of life imposed on them

by legislative, administrative or other measures; e. any form of

propaganda directed against them. 另外,宣言草案的第三部分(第12-14條)規範了原住民族的文化、宗教、以及語言權,而第四部分(第15-18條)則規定原住民族的母語受教權、以及媒體權。 美洲國家組織的「人權委員會[48]」在1997年,也通過了一份類似的『美洲原住民族權利宣言草案[49]』,除了列舉包括文化權、宗教權、以及語言權在內的原住民族集體權(第2條),並在第三部分詳細規範原住民族的文化發展(第7-13條),尤其是要求國家應該承認、並尊重原住民族的生活方式、習慣、傳統、社會經濟暨政治組織、制度、風俗、信仰、價值、服飾、以及語言(第7條);另外,母語受教權也被提到(第7條)。 聯合國大會終於在今年(2007)通過『原住民族權利宣言[50]』(見附錄1),包含原住民族有權維持獨特政治、司法、經濟、社會、以及文化制度(第5條);反同化的權利(第8條);認同權(第9條);有權綁有文化傳統,包括考古地點、史跡、藝品、設計、儀式、技術、藝術、以及文學(第11條);宗教權(第12條);文化復育權(第13條);教育權(第14條);文化尊嚴權(第15條)、以及媒體權(第16條)。 另外,在文化資產(cultural heritage)方面,「文化暨智慧財產權[51]」(cultural and intellectual

property rights )是原住民族亟需保護的文化權。在1993年通過的『生物多樣性公約[52]』,特別在第8條規範國家必須尊重原住民族的傳統知識: Each Contracting

Party shall, as far as possible and as appropriate: (j) Subject to

its national legislation, respect, preserve and maintain knowledge,

innovations and practices of indigenous and local communities embodying

traditional lifestyles relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of

biological diversity and promote their wider application with the approval

and involvement of the holders of such knowledge, innovations and practices

and encourage the equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the

utilization of such knowledge, innovations and practices; 在國內,『中華民國憲法』在總綱,有提到「各民族一律平等」(第5條);此外,在有關人民權利義務的第二章,也有「不分男女、宗教、種族、階級、黨派,在法律上一律平等」的用詞(第7條)。不過,一直要到1994年的三次修憲,增修條文(第10條)才明確地提及原住民的地位: 國家對於自由地區原住民之地位及政治參與,應予保障;對其教育文化、社會福利及經濟事業,應予扶助並促其發展。… 要到1997年的四次修憲,透過增修條文第10條的修訂,才終於出現真正對於多元文化主義的宣示: 國家肯定多元文化,並積極維護發展原住民族語言及文化。 國家應依民族意願,保障原住民族之地位及政治參與,並對其教育文化、交通水利、衛生醫療、經濟土地及社會福利事業予以保障扶助並促其發展,其辦法另以法律訂之。… 當然,在2000年通過的『大眾運輸工具播音語言平等保障法』,算是直接有關族群語言權保障的特別例立法;由行政院文化建設委員會所主推的『國家語言發展法』,是目前唯一與族群文化發展比較有關的草案。由於原住民族權利運動的努力,政府漸次訂定相關文化權保障的『原住民族教育法』(1998)、『原住民身分法』(2001)、以及『原住民族基本法』(2005)[53],規範原住民族的教育權、身分權、傳統知識暨智慧創作保護權、語言權、以及媒體權;另外,『姓名條例』(第1、2條)規定原住民可以依據文化慣俗命名。行政院原住民族委員會此刻也正在推動下列與文化權保障相關的草案,包括『原住民族認定法』、『原住民族生物多樣性保障法』、以及『原住民族語言發展法』。 伍、結論 到目前為止,文化權可以被廣義解釋為少數族群的集體權利,因此,幾乎是包括所有層面的權利;當然,如果是把定義縮小到容易操作的情況,又可能把文化權矮化為文化資產、甚至於是有形的文化資產;折衷的方式,應該是至少要包括自我認同、生活方式、以及文化資產。在過去,對於原住民族文化權的侵犯,主要是來自國家的同化政策、以及其他族群對於文化差異的敵視。現在,在多元文化主義的理想下,不管是國家、還是其他族群,大致於不敢公開排斥原住民族的文化特色;不過,畢竟還是停留在物化欣賞的層次。真正要實踐原住民族的文化權,必須由國家主動出面推動,來補償四百多年來墾殖社會的文化剝奪。 附錄1:『原住民族權利宣言』(2007) Article 5 Indigenous

peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinct political,

legal, economic, social and cultural institutions, while retaining their

right to participate fully, if they so choose, in the political, economic,

social and cultural life of the State. Article 8 1. Indigenous

peoples and individuals have the right not to be subjected to forced

assimilation or destruction of their culture. 2. States

shall provide effective mechanisms for prevention of, and redress for: Article 9 Indigenous

peoples and individuals have the right to belong to an indigenous community

or nation, in accordance with the traditions and customs of the community or

nation concerned. No discrimination of any kind may arise from the exercise of

such a right. Article 11 1. Indigenous

peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions

and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the

past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as

archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies,

technologies and visual and performing arts and literature. 2. States

shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include

restitution, developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples, with respect

to their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken

without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws,

traditions and customs. Article 12 1. Indigenous

peoples have the right to manifest, practice, develop and teach their

spiritual and religious traditions, customs and ceremonies; the right to

maintain, protect, and have access in privacy to their religious and cultural

sites; the right to the use and control of their ceremonial objects; and the

right to the repatriation of their human remains. 2. States

shall seek to enable the access and/or repatriation of ceremonial objects and

human remains in their possession through fair, transparent and effective

mechanisms developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples concerned. Article 13 1. Indigenous

peoples have the right to revitalize, use, develop and transmit to future

generations their histories, languages, oral traditions, philosophies,

writing systems and literatures, and to designate and retain their own names

for communities, places and persons. 2. States

shall take effective measures to ensure that this right is protected and also

to ensure that indigenous peoples can understand and be understood in

political, legal and administrative proceedings, where necessary through the

provision of interpretation or by other appropriate means. Article 14 1. Indigenous

peoples have the right to establish and control their educational systems and

institutions providing education in their own languages, in a manner

appropriate to their cultural methods of teaching and learning. 2. Indigenous

individuals, particularly children, have the right to all levels and forms of

education of the State without discrimination. 3. States

shall, in conjunction with indigenous peoples, take effective measures, in

order for indigenous individuals, particularly children, including those

living outside their communities, to have access, when possible, to an

education in their own culture and provided in their own language. Article 15 1. Indigenous

peoples have the right to the dignity and diversity of their cultures,

traditions, histories and aspirations which shall be appropriately reflected

in education and public information. 2. States

shall take effective measures, in consultation and cooperation with the

indigenous peoples concerned, to combat prejudice and eliminate

discrimination and to promote tolerance, understanding and good relations

among indigenous peoples and all other segments of society. Article 16 1. Indigenous

peoples have the right to establish their own media in their own languages

and to have access to all forms of non-indigenous media without

discrimination. 2. States

shall take effective measures to ensure that State-owned media duly reflect

indigenous cultural diversity. States, without prejudice to ensuring full

freedom of expression, should encourage privately owned media to adequately

reflect indigenous cultural diversity. 參考文獻 Albro,

Robert, and Joanne Bauer. 2005. “Introduction,” in Robert Albro,

and Joanne Bauer, eds. Cultural Rights: What They Are, Why They Matter,

How They Can Be Realized, pp. 2-3. New York: Carnegie Council on

Ethnics and International Affairs. Alston,

Philip. 2001. “Introduction,” in Philip Alston, ed. Peoples’

Rights, pp. 1-6. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Baehr,

Peter R. 1999. Human Rights: Universality in Practice.

Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave. Benhabib,

Seyla. 2002. The Claims of Culture: Equality and Diversity in

the Global Era. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Craven,

Matthew. 1994. “The Right to Culture in the International

Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights,” in Rod Fisher, Brian

Groombridge, Julia Häusemann, and Ritva Mitchell, eds. Human Rights and

Cultural Policies in a Changing Europe: The Right to Participate in Cultural

Life, pp. 161-71. Helsinki: Arts Council of Finland. Crawford,

James, ed. 1988. The Rights of Peoples. Oxford:

Clarendon Press. Daes,

Erica-Irene. 1993. “Study on the Protection of the Cultural and

Intellectual Property of Indigenous Peoples.” (E/CN.4/Sub.2/1993/28). Dalton, Jennifer E. 2005. “International Law and the

Right of Indigenous Self-Determination: Should International Norms Be

Replicated in the Canadian Context?” Queen’s Institute for

Intergovernmental Relations Working Paper, No. 1 (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=932467#PaperDownload)

(2007/ 10/28). Das, Veena. 1994. “Cultural Rights and the

Definition of Community,” in Oliver Mendelsohn, and Upendra Baxi,

eds. The Rights of Subordinated Peoples, pp. 117-58. Delhi:

Oxford University Press. Green, Leslie. 1995.

“Internal Minorities and Their Rights,” in Will Kymlicka, ed. The Rights

of Minority Cultures, pp.256-72. Oxford: Oxford University

Press. Harvey,

Edwin R. 1996. Implementation of Cultural Rights of Minorities

in Latin America. UNESCO (http://www.puentes.gov.ar/educar/servlet/Downloads/S_BD_

POLITICASCULTURALES/UNESCO05.PDF) (2007/10/28). Häusemann,

Julia. 1994. “The Right to Participate in Cultural Rights,” in

Rod Fisher, Brian Groombridge, Julia Häusemann, and Ritva Mitchell, eds. Human

Rights and Cultural Policies in a Changing Europe: The Right to Participate

in Cultural Life, pp. 109-60. Helsinki: Arts Council of Finland. Hunt,

Paul. 2000. “Reflections on International Human Rights Law and

Cultural Rights,” in Margaret Wilson, and Paul Hunt, eds. Culture, Rights

and Cultural Rights: Perspectives from the South Pacific, pp.

25-46. Wellington: Huia Publishes. Koivunen,

Hannele, and Leena Marsio. 2007. Fair Culture? Ethnical

Dimension of Cultural Policy and Cultural Rights. Helsinki:

Ministry of Education. Kukathas,

C. 1992. “Are There Any Cultural Rights?” Political Theory,

Vol. 20. No. 1 (EBSCOhost Full Display). Kymlicka,

Will. 1995. Multicultural Citizenship. Oxford:

Oxford University Press. Kymlicka,

Will. 1989. Liberalism, Community and Culture.

Oxford: Clarendon Press. Lerner,

Natan. 1991. Group Rights and Discrimination.

Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff. Levy,

Geoffrey Brahm. 2001. “Liberal Nationalism and Cultural Rights.” Political

Studies, Vol. 49, pp. 670-91. Levy,

Jacobs T. 1997. “Classifying Cultural Rights,” in Ian Shapiro,

and Will Kymlicka, eds. Ethnicity and Group Rights, pp. 22-66.

New York: New York University Press. Margalit,

Avishai, and Moshe Halbertal. 2004. “Liberalism and the Rights to

Culture.” Social Research, Vol. 71, No. 3, pp. 529-48. Marks,

Stephen P. 2003. “Defining Cultural Rights,” in Morten Bergsmo,

ed. Human Rights and Criminal Justice for the Downtrodden: Essays in

Honour of Asbjørn Eide, pp. 293-324. Leiden: Marinus Nijhoff

Publishers. Niéc,

Halina. 1994. “The Concept of Culture in the Context of Human

Rights,” in Rod Fisher, Brian Groombridge, Julia Häusemann, and Ritva

Mitchell, eds. Human Rights and Cultural Policies in a Changing Europe:

The Right to Participate in Cultural Life, pp. 172-89. Helsinki:

Arts Council of Finland. Niezen,

Ronald. 2003. The Origins of Indigenism: Human Rights and the

Politics of Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press. Prott,

Lyndel V. 1988. “Cultural Rights as Peoples’ Rights in

International Law,” in James Crawford, ed. The Rights of Peoples, pp.

93-106. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Robbins,

Bruce, and Elsa Stamatopoulou. 2004. “Reflections on Culture and

Cultural Rights.” South Atlantic Quarterly, Vol. 103, Nos.2-3,

pp. 419-34. Stamatopoulou,

Elsa, and Joanne Bauer. 2004. “Why Cultural Rights Now.” (transcripts from Carnegie Council on Ethnics and

International Affairs) (http://www.cceia.org/ resources/transcripts/5006.html)

(2007/10/16). Symonides, Janusz. 1998. “Cultural Rights: A

Neglected Category of Human Rights.” International Social Sciences

Journal, Vol. 50, No. 158, pp. 559-72. Tamire,

Yael. 1993. Liberal Nationalism. Princeton:

Princeton University Press. Thaman,

Konai Helu. 2000. “Cultural Rights: A Personal Perspective,” in

Margaret Wilson, and Paul Hunt, eds. Culture, Rights and Cultural Rights:

Perspectives from the South Pacific, pp. 1-11. Wellington: Huia

Publishes. Thornberry,

Patrick. 1995. “The UN Declaration on the Rights of Person

Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities:

Background, Analysis, Observations, and an Update,” in Alan Phillips, and

Allan Rosas, eds. Universal Minority Rights, pp. 13-76. Turku:

Åbo Akademi University Institute for Human Rights. United

Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2004. Human Development

Report 2004: Cultural Liberty in Today’s Diverse World. New York:

United Nations Development Programme United Nations Educational, Scientific, and

Cultural Organization (UNESCO). n.d.

“General Introduction to the Standard-setting Instruments of UNESCO.” (http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=23772&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html)

(2007/10/23). Waldron, Jeremy. 1995. “Minority

Cultures and the Cosmopolitan Alternatives,” in Will Kymlicka, ed. The

Rights of Minority Cultures, pp. 93-119. Oxford: Oxford University

Press. Wilson,

Margaret. 2000. “Cultural Rights: Definitions and Contexts,” in

Margaret Wilson, and Paul Hunt, eds. Culture, Rights and Cultural Rights:

Perspectives from the South Pacific, pp. 13-23. Wellington: Huia

Publishes.

* 發表於中國人權協會主辦「2007年原住民族人權保障理論與實務研討會」,台北,台灣大學社會科學院國際會議廳,2007/11/2。 [1] Constitution of

the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, 1954。 [2] Alston(2001: 2)稱之為「peoples’ rights」,Crawford(1988)稱之為「rights of peoples」;大體而言,第三代人權還包括發展權、環境權、以及和平權(Baehr, 1999)。 [3] Thaman(2000: 1)甚至於將文化權當作是少數族群權利的同義詞。 [4] 有關於原住民族權是否算是一種三代人權,見Mary Ellen Turpel(Dalton, 2005: 1-2)。 [5] Green(1995: 259)認為,少數族群的權利除了說因為(because)有少數族群的身分而取得;另外一種說法是,即使(even when)有少數族群的身分,更不可以加以剝奪。 [6] 參見Kymlicka(1995: 76-77)的「社會文化」(societal culture),包括共同的記憶、價值觀、制度、以及習慣,使成員的在社會、教育、宗教、休閒、以及經濟等生活方式,能變得有意義。 [7] Kymlicka(1995: 18)甚至於將文化視為民族(nation、people)的同義詞,也就是一般所謂的族群。 [8] 一般又稱之為「全盤的」(holisitc)定義(Wilson, 2000: 16)。 [9] World Conference on Cultural Policies。 [10] Mexico City

Declaration on Cultural Policies, 1982。 [11] Asbjørn Eide(Marks, 2003: 296)也有類似的說法;參考Koivunen與Marsio(2007: 8-9)。 [12] United Nations

Development Programme,簡寫為UNDP。 [13] Human

Development Report2004: Cultural Liberty in Today’s Diverse World。 [14] Stamatopoulou與Bauer(2004)的清單包括教育權、文化生活參與權、享受科學進步的好處、享有道德暨物質利益的保護、以及科學研究暨創意活動的自由。請參考Koivunen與Marsio(2007: 21-22)、以及Harvey(1996)。 [15] 又稱為「團體權」(group rights)、或是「社群權」(community rights),也就是前面所謂的共同權。在這裡,權利所有者是指少數族群。不過,也有一些國家主張,為了防止強權的文化侵略,國家應該享有文化權(Stamatopoulou &

Bauer, 2004; Robbins & Stamatopoulou, 2004)。 [16] Framework

Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, 1995。 [17] 他的用字是「團體差異權」(group-differentiated rights)(Kymlicka, 1995: 26)。 [18] 反對的看法,見Kukathas(1992)、以及Waldron(1995)。 [19] Yael Tamir(1993)雖然也是由自由主義出發,不過,她對於少數族群文化權的重視,強調的是個人有權決定其文化上的歸屬,也就是認同的建構。請看Levy(2001)對於兩者觀點的比較。 [20] Tamir(1993: 37)稱之為「父權式的陷阱」(paternalistic trap)。 [21] Tamir(1993: 36)直言稱之為工具性。 [22] 這是一種本質化(essentialized)的認同定義;參見Das(1994: 123)所謂「文化的雙重生命」,一方面賦予自我認同,另一方面,卻有將認同綁死的危險。 [23] 有關文化相對主義(cultural relativism)的批判,見Niezen(2003)、以及Benhabib(2002)。 [24] Universal

Declaration of Human Rights, 1948。 [25] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,

1966。 [26] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural

Rights, 1966。 [27] Convention on

the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, 1979: States Parties shall take all

appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in other areas

of economic and social life in order to ensure, on a basis of equality of men

and women, the same rights, in particular: (a) The right to family

benefits; (b) The right to bank loans, mortgages

and other forms of financial credit; (c) The right to participate in

recreational activities, sports and all aspects of cultural life. [28] Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989: 1. States Parties recognize the

right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational

activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in

cultural life and the arts. 2. States Parties shall respect

and promote the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and

artistic life and shall encourage the provision of appropriate and equal

opportunities for cultural, artistic, recreational and leisure activity. [29] Declaration on

the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious or

Linguistic Minorities, 1992。 [30] American

Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, 1948。 [31] Additional

Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic,

Social And Cultural Rights, 1988,又稱為『美洲公約之聖薩爾瓦多議定書』(San Salvador Protocol to the

American Convention)。 [32] African Charter

on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1981。 [33] Charter of

Fundamental Rights of European, 2000。 [34] European Charter

for Regional or Minority Language, 1992。 [35] 請參考歐洲理事會在1954年公過的『歐洲文化規約』(European Cultural

Convention, 1954)、以及『文化多樣性宣言』(Declaration of the

Committee of Minister on Cultural Diversity, 2000)。 [36] Framework

Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, 1995。 [37] Hague

Recommendations Regarding the Linguistic Rights of National Minorities, 1996。 [38] Oslo

Recommendations Regarding the Linguistic Rights of National Minorities and

Explanatory Note, 1998。 [39] Convention

against Discrimination in Education, 1960。 [40] Declaration of

the Principles of International Cultural Co-operation, 1966。 [41] Declaration on

Race and Racial Prejudice, 1978。 [42] Universal

Declaration on Cultural Diversity, 2001。 [43] International Labor

Organization,簡稱為ILO。 [44] Convention

Concerning the Protection and Integration of Indigenous and Other Tribal and

Semi-Tribal Populations in Independent Countries, 1957,簡稱ILO Convention 107。 [45] Convention Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in

Independent Countries, 1989,簡稱為ILO Convention 169。 [46] UN Working Group on

Indigenous Populations,簡稱UNWGIP。 [47] United Nations Draft Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples, 1993。 [48] Inter-American

Commission on Human Rights,簡稱IACHR。 [49] Proposed

American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 1997。 [50] United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples, 2007。 [51] 有關這些名詞的釋意,見Daes(1993)。 [52] Convention on

Biological Diversity, 1992。 [53] 值得一提的是,不少現有法律也涉及原住民族的文化權,譬如『公務人員考試法』、『教育基本法』、『國民教育法』、『終身學習法』、『有線廣播電視法』、以及『文化古蹟保存法』。 |