|

原住民族的環境權* |

|||||||||||||||

|

施正鋒 淡江大學公共行政學系暨公共政策研究所教授 吳珮瑛 台灣大學農業經濟學系教授 |

|||||||||||||||

|

…

the precise relationship between human rights and environmental protection is

far from clear. Michael

R. Anderson(Acevedo,

2000: 449-50) Successfully

placing personal entitlements within the category of human rights preserves

them from the ordinary political process. Rights may thus significantly

limit the political will of a democratic majority, as well as a dictatorial

minority. Dinah Shelton(2001:

191) 壹、前言 所謂「原住民族的環境權」(indigenous peoples’

environmental rights),顧名思義,是指在「人權[1]」(human rights)的範疇裡頭,究竟「原住民族權[2]」(indigenous rights)包括多少「環境權[3]」(environmental rights)。乍看之下,我們或以為這三種權利似乎有某種相互從屬的關係,也就是說,在人權這個大旗幟之下,可以有各形各色的人權類別;如果以Karel Vasak 人權發展三代論來看[4](Baehr, 1999: 6; Donnelly, 1989:

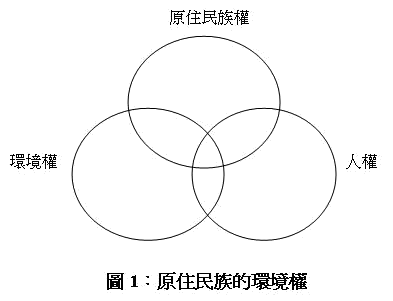

143-45),也就是屬於第一代人權的公民權[5]、以及政治權(civil、political rights)、屬於第二代人權的經濟權、社會權、以及文化權(economic、social、cultural rights)、以及屬於第三代人權的共同權[6](rights of solidarity),那麼,環境權、以及原住民族權利都可以算是三代人權裡頭的兩種共同權[7]。 然而,不論是從概念上、或是國際法的實際運作而言,人權、環境權、以及原住民族權,三者並沒有體系上的上下位關係(hierarchy);也就是說,人權(傳統、狹義、一般性)是比較注重個人的權利,環境權持有者(bearer、holder)是所有的人類,而原住民族權的主體是原住民族。因此,儘管三者有所交集(圖1),然而,並非所有的人權規範,直接與環境權、或是原住民族權的保障有相關;同樣地,並非所有的環境權關懷,可以看出與一般人權、或是原住民族權推動的關聯;當然,也不是所有的原住民族權的追求,與一般人權、或是環境權的實踐有直接關係。

最早正式提出環境保護與人權關係的,是聯合國大會在1968年通過的決議〈人類環境之問題[8]〉,認為人類環境品質的惡化,可能會影響到「基本人權之享受」: Noting, in

particular, the continuing and accelerating impairment of the quality of the

human environment caused by such factors as air and water pollution, erosion

and other forms of soil deterioration, waste, noise and the secondary effects

of biocides, which are accentuated by rapidly increasing population and

accelerating urbanization, Concerned about

the consequent effects on the condition of man, his physical, mental and

social well-being, his dignity and his enjoyment of basic human rights, in

developing as well as developed countries, 接下來,聯合國在1972年於斯德哥摩舉行的「人類環境會議[9]」,提出『斯德哥摩宣言[10]』,開宗明義揭示環境與人權的關係(第1原則),也就是說,除了間接點到環境品質與生命權不可分開,而且也強調人類保護環境的責任: Man

has the fundamental right to freedom, equality and adequate conditions of

life, in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and

well-being, and he bears a solemn responsibility to protect and improve the

environment for present and future generations. 不過,真正提及環境權概念的,是非洲團結組織[11]在1981年通過的『非洲人權憲章[12]』(第24條): All peoples shall have the right to a

general satisfactory environment favorable to their development. 另外,美洲國家組織[13]在1988年通過『美洲社會、經濟、暨文化權規約附加議定書[14]』,也有類似環境權的規定(第11條、健康環境權): 1. Everyone shall

have the right to live in a healthy environment and to have access to basic

public services. 2. The States Parties shall promote

the protection, preservation, and improvement of the environment. 國際勞工組織[15]在1989年通過『原住暨部落民族公約[16]』,雖然有專章提到原住民族的土地,不過,重點是原住民族隊於傳統所佔有土地的所有權(第14.1條): The rights of ownership and possession

of the peoples concerned over the lands which they traditionally occupy shall

be recognised. In addition, measures shall be taken in appropriate

cases to safeguard the right of the peoples concerned to use lands not

exclusively occupied by them, but to which they have traditionally had access

for their subsistence and traditional activities. Particular attention

shall be paid to the situation of nomadic peoples and shifting cultivators in

this respect. 首先提及原住民族與環境關聯的,是聯合國在1992年於里約熱內盧舉行的「環境暨發展會議[17]」所提出的『里約熱內盧環境暨發展宣言[18]』(第22項原則),主要是在陳述原住民族對於環境管理與發展的重要角色: Indigenous people and their communities,

and other local communities, have a vital role in environmental management

and development because of their knowledge and traditional practices.

States should recognize and duly support their identity, culture and

interests and enable their effective participation in the achievement of

sustainable development. 在這樣的脈絡下,在同時間通過的行動綱領『二十一世紀議程[19]』,雖然強調原住民族與土地的歷史關係,不過,其實還是在說明原住民族如何參與自然環境與永續發展之間的關係(第26.1條): Indigenous people and their

communities have an historical relationship with their lands and are

generally descendants of the original inhabitants of such lands. In the

context of this chapter the term "lands" is understood to include

the environment of the areas which the people concerned traditionally

occupy...They have developed over many generations a holistic traditional

scientific knowledge of their lands, natural resources and environment.

Their ability to participate fully in sustainable development practices

on their lands has tended to be limited as a result of factors of an

economic, social and historical nature. In view of the

interrelationship between the natural environment and its sustainable

development and the cultural, social, economic and physical well-being of

indigenous people, national and international efforts to implement

environmentally sound and sustainable development should recognize,

accommodate, promote and strengthen the role of indigenous people and their

communities. 在下面,我們先將先後分別探討環境權與人權之間的關聯、以及環境權與原住民族權之間的關係;接著,我們要考察究竟環境的內在價值有何意義;然後,我們在提出結語之前,要看現有的國際規約、或是宣言,對於原住民族的環境權有何種規範。 貳、環境保護與人權保障的關係 以人權保障的角度來看環境保護,儘管學者同意兩者有所關連[20],不過,正如Michael R. Anderson所言,「人權與環境保護的關係並不是那麼清楚」(Acevedo, 2000:

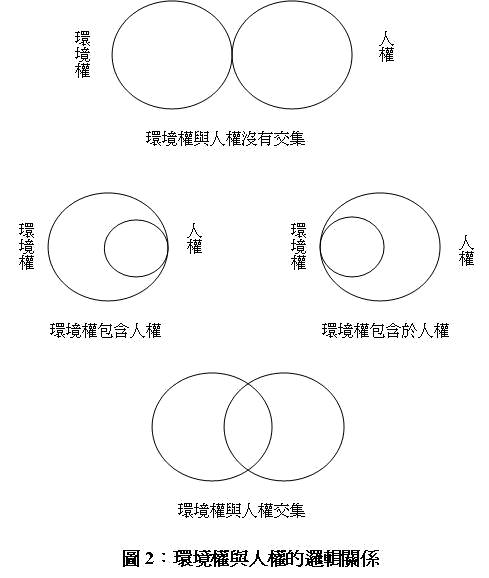

449-50)。就邏輯上而言,人權與環境權可以有四種可能的關係[21],包括兩者沒有交集、環境權包含人權、環境權包含於人權、以及環境權與人權有某些交集(圖2)。 我們根據Acevedo(2000)、Anderson(1996)、Dias(2000)、Fabra(2002)、Purdon(2006)、以及Shelton(2001; 1991-1992),可以歸納四種觀點,來觀察環境保護與人權保障之間的關係。第一種看法是「環境權工具論」,也就是說,環境保護本身不是目標,而是為實踐基本人權這個終極目標的工具[22]、或是「應該享有的環境權利[23]」;具體而言,環境品質下降之際(譬如污染、農藥、油輪漏油),人們的生命、健康、以及生活等權利會直接受到影響,因此,只要有任何行為破壞環境,就會立即侵犯到國際上公認的基本人權(Acevedo, 2000: 452;

Shelton, 2001: 187-89)。這個途徑的最大優點,是可以運用現有的人權機制來要求環境品質低落的國家改善;不過,如果面對的是對於生態、或是物種的傷害,由於當前人權保障的對象是人,也就無法直接保護環境(Shelton, 2001: 188)。 第二種看法是「環境權目標論」,將環境保護、或是永續發展當作是最終的目標,然後,再由現有的人權機制當中,看何者有利於環境權的保障,因此,人權保障反而變成是工具,特別是資訊權、政治參與權、以及補償權,不用擔心環境保護是否有助於一般人權的保障;譬如說,環保運動成員成立非政府組織的自由、或是有權利取得對於環境有潛在傷害的資訊(Shelton, 2001: 187、190)。不過,儘管人權監督機制相當完備,相較之下,現有的國際環境保護協定對於各國的約束力較低,可能無法達到立竿見影的效果(同上)。

第三種看法是第二種看法(環境權目標論)的修正,或是第一種看法與第二種看法的合成(環境權既是工具、也是目標)(Acevedo, 2000:

453-54; Kastrup, 1997; Shelton, 2001: 188),嘗試著以第一代人權為基礎(basis)、或發射點(launching

point),來衍生(derive)、或是延伸(extend)出屬於第三代人權的環境權;換句話說,這裡的做法是想辦法將人權的範疇作擴大解釋,希望能將以人權的途徑來看環境保護。具體而言,就是開始嘗試著去把生態平衡、以及永續發展等目標,整合在環境權的範疇裡(Acevedo, 2000: 452;

Anderson, 1996; Eckstein與Gitlin, 1995;

Shelton, 2001: 188)。 第四種看法則由責任的角度來看環境保護,也就是說,根本反對以人權的觀點來看環境保護,當然,不會關心到底環境保護與人權有何關聯(Shelton, 2001:

188-89)。 我們如果不去討論第四種觀點(也就是人權與環境權沒有任何關聯),可以將人權保障與環境保護之間的關係,歸納成兩大類。第一大類是認為彼此有工具、或是目標之間的從屬關係:就第一種觀點而言,人權是目標、環境保護是手段,也就是說,環境保護是保障人權的必要條件,隱含著人權包含著環境權;相對地,第二種觀點是將環境保護列為目標、人權保障是手段,也就是說,人權保障是環境保護的手段,實際上是意味著環境權包含著人權。第二大類則不去計較兩者究竟何者為目標、何者為工具,這也就是第三種觀點所關心的,也就是說,如何由人權保障推演出環境保護的權利。 然而,誠如Shelton(2001: 190)所言,並非所有一般人權保障的措施與環境保護有所關聯,因此,如果要根據人權推動者的看法,要人權保障能完全吸納環境保護(環境權工具論),也是過於牽強;相對地,如果要根據環境保護者的看法,要環境保護完全吸納人權的範疇(環境目標論),勢必要調整(縮減)人權這個概念的內涵,甚至於只剩下程序權,影響所及,很可能會讓人權的面目不可辨識。 事實上,環境保護與人權保障不僅是無法相互從屬(也就是一個被另一個全部吸納),甚至於,有可能彼此在目標上是相互競爭的。以Shelton(2001: 190-91)所提到的「環境正義」(environmental justice)概念來看[24],追求的目標包括「同一世代的公平」(intragenerational

equity)、「世代之間的公平」(intergenerational

equity)、以及「物種之間的公平」(interspecies equity);人權保障主要是關心同一世代的公平,相對地,環境保護關懷的是世代之間、甚至於物種之間的公平,因此,彼此所追求的目標未必都是相輔相成。我們可以這樣說,環境權與人權是彼此有交集,各自「代表著不同、但是重疊的社會價值,卻又有共同的目標作核心」(Watters, 2001-2002);只不過,前者是「以環境保護的途徑來看人權保障」,後者則是「以人權保障的途徑來看環境保護」。 如果根據傳統三代人權的分類方式,也就是第一代人權(公民權、以及政治權)、第二代人權(經濟權、社會權、以及文化權)、以及第三代人權(環境權、和平權、以及發展權),那麼,環境權似乎與第一代人權、或是第二代人權沒有相關;其實不然,我們如果由從實質面、以及程序面來看環境權,也就是以環境權的工具論觀點,把實質權(substantive rights)當作追求的標準,同時,以環境權的目標論觀點,把程序權(procedural rights)當作實踐的工具(Acevedo, 2000: 454-58; Kolari,

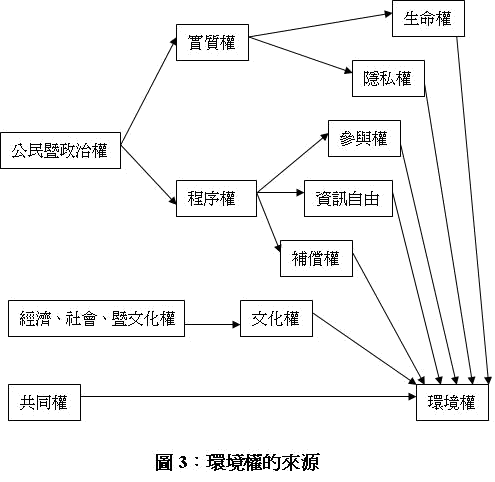

2004: 5),那麼,我們其實可以看出環境權的來源,還是有相當大的一部分是第一代人權、或是第二代人權推演出來[25](圖3)。 就第一代人權而言,本質上是負面的權利,也就是說,如何保障個人的權利(包括公民權、以及政治權)不被政府侵犯。首先,就實質權而言,生命權、以及隱私權可以視為推演環境權的出發點;如果由國家的「正面義務」來看,國家必須採取合乎國際標準的環境保護措施,以便保障人民的生命權;另外,包括污染在內的各種環境品質破壞,也被視為侵犯到個人的隱私權(Acevedo, 2000:

455-56)。 就程序權而言,公共參與權、資訊自由、以及補償權與環境權的關聯比較直接。公共參與權是指可能受到環境政策影響的人,有權利參與環境未來的決策[26],特別是被傾聽的權利(right to be heard)、以及影響決策的權利(right to affect decision)(Shelton, 2001: 203-4)。接著,資訊自由/資訊接近權(access to

information)是指人們為了維持生活品質,有權獲得有關環境風險、或是降低風險的資訊,特別是在因為政府的作為造成環境壞之際,人們更是有取得相關資訊的自由(Acevedo, 2000: 457:

Shelton, 2001: 199-203)。再來,補償權/司法接近權(access to justice),是指人們在遭受環境破壞之際,有權透過司法、或是行政的程序,取得有效的彌補、或是賠償(Shelton, 2001:

209-10)。

就第二代人權而言,本質上是比較正面的權利,要求政府積極介入經濟、社會、以及文化價值的生產、或分配;如果從環境權工具論的觀點來看,這些算是實質的權利,本身就是目標,因此,當前的一些相關規約的監督機制比較具體,也可以用來作為要求環境品質的依據(Acevedo, 2000:

458-59)。不過,這些權利的保障與環境保護之間的關係,到目前為止,並不是那麼明顯(dubious),一直要到原住民族的文化權被帶入以後,人權保障與環境保護的關係就會豁然開朗。 就第三代人權而言,環境權本身就是一種「明確的權利」(express right),未必要間接從第一代人權、或是第二代人權衍生而來(Acevedo, 2000:

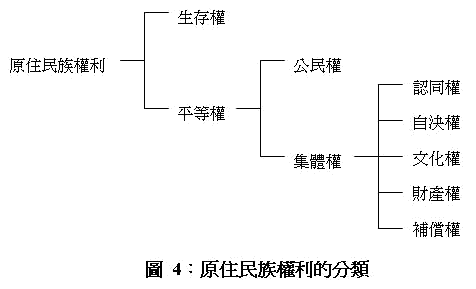

462-63)。不過,到目前為止,只有年通過的『非洲人權憲章』(1981)、以及『美洲社會、經濟、暨文化權規約附加議定書』(1988),明白地提到人們享有健康環境的權利。 參、環境權與原住民族權利的關係 在國際法的領域,對於環境的保保護、以及原住民族權利的保障,幾乎是同步在發展的(Kastrup, 1997)。我們先前(施正鋒,2005:33-38),曾經根據聯合國『原住民權利宣言草案[27]』(1993),把原住民的權利概分為生存權(第6條)、以及平等權兩大類:生存權/生命權關切的是如何保障原住民的起碼生存,而平等權則要積極地推動原住民的基本權利。我們又可以將平等權區分為公民權(第2、5條)、以及集體權:前者關心的是如何確保原住民個人不被歧視;後者則以原住民集體為關照的單位,包括認同權(第8條)、自決權(第3條、第7部分)、文化權(第7條、第3、4部分)、財產權(第6部分)、以及補償權(第27條)。我們將這些權利整理如下(圖4):

我們根據S. James Anaya(1999-2000: 6-9)的分類方式,可以使用生命權/生存權、文化權、財產權、以及自決權等四種規範,分別來說明原住民族應該享有環境權。首先,就生命權的角度來看,健康的環境決定了原住民族是否可以享有生命權所必須的物質福祉;在這裡,環境權的主體是原住民族、而非自然環境。 再來,就文化權而言,由於原住民族有權保有其文化特色,而自然環境、以及土地資源又是維繫其獨特的文化所必須,因此,在保障原住民族文化權的脈絡下,自然環境的保護是必要的條件,特別是土地(Cohan, 2001-2002:

155);不過,Anaya(1999-2000: 7)提醒我們,在這裡,環境權是透過文化權間接導引出來的,兩者並不等同,也因此,原住民族的文化習俗,未必與環境保護的目標完全契合。 接下來,是原住民族的財產權,也就是原住民族對於其傳統土地/領域(traditional lands、或是territory)合理取得(possession)、以及使用(use)而擁有所有權(ownership)、或是財產權(property)。另外,值得一提的是,即使國家同意原住民族擁有其傳統領域,卻往往認為地表下的資源仍然屬於國家,尤其是拉丁美洲國家;在這樣的情況下,即使原住民族只擁有地表,國家在開採地下資源之際,仍然要取得原住民族的同意(Anaya, 1999-2000:

8-9)。 最後,與原住民族環境權有關的是自決權,也就是原住民族有權決定自己的命運,具體而言,政府進行有關於自然資源的開採、或是開發之際,必須事先徵詢原住民族的意見,同時,必須讓原住民族自主參與決策(Anaya, 1999-2000: 9)。 我們以光譜的方式,來整理上述賦予原住民族環境權的四種規範(圖5)。就生存權的層面來看,原住民族權利運動與環境保護運動所關懷的大致上是一致的,也就是在對於環境污染所造成的生存危機上面,彼此的目標是相同的。然而,就文化權的觀點來看,兩者所追求的利益未必就一定會相容,特別是生態保育的要求如果被視為是無限上綱之際,很有可能會危及原住民族的生活方式、或是傳統文化。同樣地,就財產權而言,墾殖國家往往不顧歷史上的掠奪,將原住民族的傳統土地收為國有,只留下非原住民政府認為原住民族個人所需的土地。最後,就自決權而言,國家往往會站在所謂「國家利益」的角度,罔顧原住民族的意願,逕自進行原住民族土地的護育、開發、或是利用。由此看來,原住民族權利與環境權只有交集的關係,而非兩者作某種的相互包含,也就是說,在生命權方面,彼此可能比較會互補,至於文化權、財產權、或是自決權的實踐,也就是源自集體權的部分,比較可能會出現互斥的情形。

就台灣原住民族的環境權來看,最起碼的要求是生存權,特別是廢棄物的堆集,譬如說蘭嶼的核廢料,已經危及達悟民族的生存。再來是文化權,尤其是傳統的生活方式被剝奪,譬如說『野生動物保育法[28]』(第21.1條)對於原住民族狩獵的限制。接下來是財產權,特別是傳統領域的土地被剝奪,譬如說把原住民族的土地被限定在保留地的範圍。最後是自決權,尤其是原住民族的土地被恣意劃為水資源用地(集水區、水源水質水量保護區)、森林用地(國有林班地之中的保安林)、或是自然生態保護區裡頭的國家公園[29],譬如石門水庫、以及規畫中的馬告國家公園、或是瑪家水庫[30]。 我們從上述這四個層面來看,台灣原住民族在嘗試實踐環境權之際,事實上是面對多重的挑戰,也就是說,由環境權來作切入點,台灣原住民族人權保障與環境保護雖然有可能是相輔相成,然而,也有可能是相互排斥、甚至於衝突[31]。在過去,台灣的環境保護運動與原住民族權利運動相互提攜,然而,在民進黨於2000年執政以來,兩者的矛盾開始浮現,也就讓我們覺得有必要重新思考環境權與原住民族權之間的關係為何。 事實上,就人類的歷史發展來看,大多數原住民族是在接觸過「白人文化」以後,學習將自然資源的開採作為商業消費、或是視為族人發展的最重要依據,才逐漸發展出破壞環境的行為(Kastrup, 1997)。同樣地,一些環保人士將台灣原住民族視為破壞生態的罪人,也是無視在資本主義支配的經濟結構中,原住民族頂多只是白浪/漢人/非原住民資本家的幫兇而已。 一般而言,最基本的假設是原住民族在追求經濟發展目標之際,有可能會與環境保護的價值產生衝突,就牽涉到在原住民族環境權的脈絡下,如果將重點放在光譜的右方(圖4),也就是強調環境權的財產權、以及自決權的面向,那麼,就會出現原住民族的環境權/發展權[32]與非原住民的環境權孰重的議題。然而,當國家在進行環境價值評估之際,往往忽略到原住民族的環境權保障,也就是說,除了要考量環境資源好壞多寡以外,還必須顧及原住民族對於環境價值的認定[33]。 從程序權的角度來看,在資訊自由、以及充分參與的決策下,在國家整體利益的考量下[34],就必須補償原住民族抑制經濟發展所做的犧牲,不能讓社會上最弱勢的族群,來承擔國家提供全體國人公共财的機會成本。 問題是,如果生態學家在追求保護生物多樣性的情況下,相信這些物種本身就存有「內在價值」(intrinsic value),因此,很可能希望保護一些對人類沒有益處、甚至於有害處的物種。此時,就牽涉到底這是人的「環境權」(right to environment)、或者是「環境的權利」(rights of the environment)的問題(Dias, 2000),也就是說,究竟環境權的主體已經超越族群之間競爭的層次,而是人與物種孰重的抉擇[35]。 針對物種滅絕與其他環境問題日趨嚴重,環境倫理學者認為有必要重新檢視人類與自然間的倫理關係。西方環境倫理觀所持的是「人類中心主義」(anthropocentrism),認為物種只有「工具價值」(instrumental value),而沒有「內在價值」(intrinsic value),也就是說,物種是因能提供給人類各式各樣的實質利用,而被認定有其存在的價值。在此種環境倫理觀之下,人類並未意識到如何與物種定位,以便能持續享有物種所提供的工具性價值,也因此,物種滅絕、以及環境破壞的危機,並未有減緩、或是解除之跡象。 從1960年代開始,環境倫理學興起「非人類中心主義」(non-anthropocentrism)的看法[36],認為人類中心主義認定人類優於萬物之觀點,其實是一種狹隘的物種主義,而且是造成今日環境危機的主要原因。這些學者因此主張,物種、或生態系統本身就具有所謂的內在價值,而不是只有依附在人類的工具價值。也就是說,物種、或生態系統本身應該成為道德關懷的對象,如此才可能化解環境危機。 總之,對於人權推動者來說,如果不以人為中心,人權的標準就無法確立,一些環境倫理學者採取修正式的人類中心觀點[37],也就是嘗試著要整合兩派的看法,一方面堅持人類為資源權的主體,另一方面,也願意去承認資源的內在價值[38];同樣地,環境資源經濟學者認為,人類是在利己動機的驅動下,希望求得社會整體的最大效益的產生,包括對於生物多樣性資源總價值得認定,可以歸屬於「效用主義」(utilitarianism),也因此算是歸屬於人類中心主義的範疇(吳珮瑛、蘇明達,2003)。儘管如此,在自然資源有限的情況下,如何決定對物種維護、以及利用上的優先順序,仍然要面對原住民族作為環境權所有者的課題。 肆、國際規約、以及宣言

在這裡,我們要根據時序,說明與原住民族環境權比較有關聯的國際規約、以及宣言。戰後,對於人權保障的基礎,很明確地是建立在『聯合國憲章[39]』(1945)、以及『世界人權宣言[40]』(1948);不過,真正提到原住民族的是國際勞工組織在1957年通過『原住暨部落人口公約[41]』,特別是對於原住民土地的關心。 聯合國在1966年先後通過『國際公民暨政治權公約[42]』、以及『國際經濟、社會、暨文化權公約[43]』,除了分別規範第一代、以及第二代人權,更同時在第一條規定「所有的民族 [peoples] 享有自決權」;此外,前者也明言「所有民族可以自由處理其天然財富及資源」(第1.2條): All peoples may, for their own ends,

freely dispose of their natural wealth and resources without prejudice to any

obligations arising out of international economic co-operation, based upon

the principle of mutual benefit, and international law. In no case may a

people be deprived of its own means of subsistence. 不過,最重要的是強調少數族群的文化權不可被剝奪(第27條),而文化權與原住民族的資源權又是分不開來的: In

those States in which ethnic, religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons

belonging to such minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with

the other members of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and

practice their own religion, or to use their own language. 根據聯合國人權委員會的解釋,「文化的表現有多種形式,包括與土地資源使用相關的特別生活方式,尤其是對於原住民族而言」(Shelton, 2001: 238),因此,這可以說是由文化權衍生環境權的最明確佐證。 當然,如前所述,最先提到環境保護與人權保障的,是聯合國大會在1968年通過的〈人類環境之問題〉決議,揭示環境品質會影響到人權的看法。四年後,「聯合國人類環境會議」提出『斯德哥摩宣言』(1972),揭櫫「生命權決定於環境品質」,也就是由生命權衍生出(derivative、inferred)環境權的概念;不過,該宣言並未真正使用「環境權」的字眼,只是認為環境保護是人權保障的工具。有人批判該宣言對於責任著墨的比較多,對於環境權談得比較少(Kolari,

2004: 34)。也有人認為如果依照嚴格的解讀,應該只包括威脅到生命危險的環境破壞,因此,環境權的內涵似乎是過於狹隘(Hill,

2004)。當然,在本質上,這只是一個沒有強制約束力的文件(Kiss,

1992)。 在將近十年之後,才看到『非洲人權憲章』(1981)名正言順納入環境權的保障(第24條),而且,環境權的所有者是「peoples」,帶有集體權的意味(Hill, 2004)。 聯合國大會在1982年通過『世界自然憲章[44]』,除了在前言說到「人類是自然的一部分」、以及「所有的生命性是都是獨一無二的」以外,重點是在如何保護大自然,因此,可以說是帶入自然的「內在價值」,頂多是強調在程序上參與環境保護決策的「機會」,也是淡化了先前『斯德哥摩宣言』對於環境權的重視(Shelton, 2001: 195、198),套一句Hill(2004)的說法,其約束力更為軟性[45]。 比較特別的是「聯合國世界環境暨發展委員會[46]」,在1987年公佈的一份報告『我們的共同未來[47]』,除了有程序權的影子(頁322),還特別提到原住民族的傳統生活被經濟發展破壞、以及原住民族的傳統知識如何幫助資源的管理,並建議各國政府承認原住民族的傳統權利、以及參與資源政策的制定(Watters, 2001-2002:

268)。 回到一般性的環境權推動,美洲國家組織再次年通過『美洲社會、經濟、暨文化權規約附加議定書』(1988),用字遣詞比『非洲人權憲章』更加明確,除了確認「每個人」有環境權以外,還要求簽署國有保護、保存、以及改善環境的義務(第11條)。不過,Alston(2001b: 282)提醒我們,這裡的條文並非以共同權/集體權的方式來陳述環境權,而是指國家對於公共服務的提供,因此,還要看究竟要被作廣義、還是狹義的詮釋。 最為突出的是國際勞工組織提出修正過的『原住暨部落民族公約』(1989)(見附錄1),要求簽署國必須保護原住民族的個人、制度、財產、文化、以及環境(第4.1條): Special

measures shall be adopted as appropriate for safeguarding the persons,

institutions, property, labour, cultures and environment of the peoples

concerned.

此外,該公約除了以專章(第二部分)詳細規範原住民族土地權保障,包括原住民族文化與土地的關係(第13.1條)、傳統領域的所有權(第14.1條)、傳統領域的劃編及保護(第14.2條)、以及建立處理取回土地的司法機制(第14.3條),該條約還強調原住民族有權決定自己的土地與發展的優先順序,參與攸關自己的發展計畫的規劃、執行、以及評估,以及政府應該採取措施保護原住民族領域的環境: The peoples concerned shall have the

right to decide their own priorities for the process of development as it affects

their lives, beliefs, institutions and spiritual well-being and the lands

they occupy or otherwise use, and to exercise control, to the extent

possible, over their own economic, social and cultural development. In

addition, they shall participate in the formulation, implementation and

evaluation of plans and programmes for national and regional development

which may affect them directly. (第7.1條) Governments shall take measures, in

co-operation with the peoples concerned, to protect and preserve the

environment of the territories they inhabit. (第7.4條)

在1992年舉行的「聯合國環境暨發展會議」,雖然重申環境保護的訴求,不過,由於重點是在永續發展,加上與會人員缺乏共識,因而並不太願意使用人權的觀點來看環境保護[48](Acevedo, 2000: 451; Shelton, 2001: 196)。譬如大會所通過的『里約熱內盧環境暨發展宣言』(1992),一開頭就從『斯德哥摩宣言』的基調退卻下來,不用環境權的概念、而是用「有資格」(entitled)(第1項原則): Human beings are at the center

of concerns for sustainable development. They are entitled to a healthy

and productive life in harmony with nature 值得注意的是,該原則強調「人類與自然的和諧關係」,被解釋為是稍微偏離傳統以人為中心的環境權觀點(Kolari,

2004: 43)。整體來看,該宣言頂多是強調參與決策、資訊自由、以及司法補償對於環境保護的好處(第10項原則);同樣地,該宣言雖然承認原住民族對於環境保護的重要角色,重點卻是國家應該鼓勵認原住民族參與永續發展(第22項原則)。 同時通過的行動綱領『二十一世紀議程』(1992)(見附錄2),大體上還是強調大眾參與決策對於環境保護、以及永續發展的必要性(第23.2條),在巨細靡遺的程序權規範中,並沒有/不願意使用到環境權的字眼;這份文件雖然有專章討論原住民族的角色,不過,既然大會的基調是永續發展,即使承認原住民族與自然環境的歷史關係,也提到「夥伴關係」(partnership)、「培力/賦權」(to empower)(第26.3條)、以及「自我管理」(self-management)(第26.4條)等新穎的概念,重點還是在原住民族如何貢獻,使國家的發展能夠合乎環保、以及永續的原則(第26.1條)。 另外,相關的『生物多樣性條約[49]』(1994),也有敦促簽署國尊重原住民族對於保存生物多樣性的傳統做法(第8.j條),強調的是程序上的作為,保護的主體並非原住民族: Subject

to its national legislation, respect, preserve and maintain knowledge,

invocations and practices of indigenous and local communities embodying

traditional lifestyles relevant for the conservation and sustainable use of

biological diversity and promote their wider application with the approval

and involvement of the holders of such knowledge, innovations and practices

and encourage the equitable sharing of the benefits arising from the

utilization of such knowledge, innovations and practices... 聯合國「經濟暨社會理事會[50]」所屬的「人權委員會[51]」,下面設有「防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會[52]」,其任命的人權暨環境特別報告人[53]Fatima Zohra

Ksentini在1994年針對人權與環境提出一份最後報告[54],結論是環境權作為一種人權已被普世承認(Alston, 2001b: 282)。在這份報告的附冊『人權與環境之原則草案[55]』中,明白指出環境權(前言、第2原則),並且詳細列了各種實質權的(第二部分)、以及程序上的環境權(第三部分);比較特別的是,這份草案在實質權部分,也特別討論到原住民族與環境的關係,再度確認原住民族對於土地、領域、以及自然資源的控制權(第14原則): Indigenous peoples

have the right to control their lands, territories and natural resources and

to maintain their traditional way of life. This includes the right to

security in the enjoyment of their means of subsistence. Indigenous peoples have the right to

protection against any action or course of conduct that may result in the

destruction or degradation of their territories, including land, air, water,

sea-ice, wildlife or other resources. 聯合國防止歧視暨保護少數族群小組委員會下轄的「原住人口工作小組[56]」,也差不多在同時通過了『原住民族權利宣言[57]』(1993)(見附錄3),以專章方式宣示原住民族土地、以及資源權(第25-30條),可以說是截自目前為止,對於原住民族的土地資源,作了最為週延的規範,包括:原住民族有權維持與土地、領域、水域、以及沿海的精神、以及物質關係(第25條);原住民族有權擁有、發展、控制使用其土地、以及領域(第26條);原住民族對於傳統領域、以及資源被徵收、佔領、使用、或是污染,有權要求補償(第27條);原住民族對於其環境,有權要求維護、恢復、以及保獲(第28條);原住民族有權決定對於土地、領域、以及資源在發展上的優先順序(第25條)。 同樣地,美洲國家組織的「人權委員會[58]」草擬了一份『美洲原住民族權利宣言草案[59]』(1997)(見附錄4),其中,關於原住民族環境保護權的條款,也算是相當詳盡(第13條)。 最後,聯合國「歐洲經濟委員會[60]」在1998年通過『奧胡斯公約[61]』,針對制定環保政策的過程中,對於大眾取得資訊、參與決策、以及司法途徑的保障,重新回到『斯德哥摩宣言』第1原則所揭示的環境權概念。[62] 伍、結語 儘管Alston(2002b)對於現有國際環境法發展的看法還是有相當的保留,不過,Anaya(2005: 8)認為,原住民族對於土地、以及資源的所有權,不只是表達渴望(aspirational),也已經被國際法視為一部分,譬如在判例上面,我們可以看到不少有利的解釋(Cohan, 2001-2002;

Ercmann, 1999-2000; Manus, 2006; O’Connor, 1994; Shutkin, 1990-1991; Watters,

2001-2002),此外,不少國家的憲法也將環境權的保障列入(Boyle, Alan, and

Michael Anderson, 1996; Hill, 2004; Shelton, 2004; Anaya & Williams, 2001),尤其是拉丁美洲國家的憲法(附錄5),對於原住民族的環境權有特別的保護。 在國內方面,包括台聯政策會(2006)草擬的『台灣憲法草案』、以及21世紀憲改聯盟(2006)所提出的憲改版本,都有提到環境權的保護,不過,都沒有提及原住民族的環境權;民進黨中央黨部政策委員會(2006)所提的『民進黨憲改草案』,約略提及「保障原住民有關傳統領域、水域、礦物及其他自然資源」(第168.4條);至於原民會的『原住民族專章草案』(憲法原住民族政策制憲推動小組,2005),雖然也只有一個條款與原住民族的環境權相關,相對上,比較有明確的規範(見表1)。 表1:國內憲草的環境權條文

資料來源:施正鋒(2005: 163)、21世紀憲改聯盟(2006)、民進黨中央黨部政策委員會(2006)、以及台聯政策會(2006)。 儘管如此,如果我們由目前國內政黨、以及相關團體對於原住民族權利入憲(憲法專章)的態度來看(施正鋒,2006),委實無法樂觀。追根究底,我們還是必須回歸探討最基本的問題,究竟台灣是一個漢人的國家、還是多元族群/民族的國家?原住民族究竟是台灣的主體、還是供人裝飾/欣賞/消費/使用的客體?

附錄1:原住暨部落民族公約(1989)[63] Article 6 1. In applying the provisions

of this Convention, Governments shall: (a) Consult the peoples

concerned, through appropriate procedures and in particular through their

representative institutions, whenever consideration is being given to

legislative or administrative measures which may affect them directly; (b) Establish means by which

these peoples can freely participate, to at least the same extent as other

sectors of the population, at all levels of decision-making in elective

institutions and administrative and other bodies responsible for policies and

programmes which concern them; (c) Establish means for the

full development of these peoples' own institutions and initiatives, and in

appropriate cases provide the resources necessary for this purpose. 2. The consultations carried

out in application of this Convention shall be undertaken, in good faith and

in a form appropriate to the circumstances, with the objective of achieving

agreement or consent to the proposed measures. Article 7 1. The peoples concerned shall

have the right to decide their own priorities for the process of development

as it affects their lives, beliefs, institutions and spiritual well-being and

the lands they occupy or otherwise use, and to exercise control, to the

extent possible, over their own economic, social and cultural development. In

addition, they shall participate in the formulation, implementation and

evaluation of plans and programmes for national and regional development

which may affect them directly. 2. The improvement of the

conditions of life and work and levels of health and education of the peoples

concerned, with their participation and co-operation, shall be a matter of

priority in plans for the overall economic development of areas they inhabit.

Special projects for development of the areas in question shall also be so

designed as to promote such improvement. 3. Governments shall ensure

that, whenever appropriate, studies are carried out, in co-operation with the

peoples concerned, to assess the social, spiritual, cultural and

environmental impact on them of planned development activities. The results

of these studies shall be considered as fundamental criteria for the

implementation of these activities. 4. Governments shall take

measures, in co-operation with the peoples concerned, to protect and preserve

the environment of the territories they inhabit. PART II. LAND Article 13 1. In applying the provisions

of this Part of the Convention governments shall respect the special

importance for the cultures and spiritual values of the peoples concerned of

their relationship with the lands or territories, or both as applicable,

which they occupy or otherwise use, and in particular the collective aspects

of this relationship. 2. The use of the term

"lands" in Articles 15 and 16 shall include the concept of

territories, which covers the total environment of the areas which the

peoples concerned occupy or otherwise use. Article 14 1. The rights of ownership and possession

of the peoples concerned over the lands which they traditionally occupy shall

be recognised. In addition, measures shall be taken in appropriate cases to

safeguard the right of the peoples concerned to use lands not exclusively

occupied by them, but to which they have traditionally had access for their

subsistence and traditional activities. Particular attention shall be paid to

the situation of nomadic peoples and shifting cultivators in this respect. 2. Governments shall take steps

as necessary to identify the lands which the peoples concerned traditionally

occupy, and to guarantee effective protection of their rights of ownership

and possession. 3. Adequate procedures shall be

established within the national legal system to resolve land claims by the

peoples concerned. Article 15 1. The rights of the peoples

concerned to the natural resources pertaining to their lands shall be

specially safeguarded. These rights include the right of these peoples to

participate in the use, management and conservation of these resources. 2. In cases in which the State

retains the ownership of mineral or sub-surface resources or rights to other

resources pertaining to lands, governments shall establish or maintain

procedures through which they shall consult these peoples, with a view to

ascertaining whether and to what degree their interests would be prejudiced,

before undertaking or permitting any programmes for the exploration or

exploitation of such resources pertaining to their lands. The peoples

concerned shall wherever possible participate in the benefits of such

activities, and shall receive fair compensation for any damages which they

may sustain as a result of such activities. Article 16 1. Subject to the following

paragraphs of this Article, the peoples concerned shall not be removed from

the lands which they occupy. 2. Where the relocation of

these peoples is considered necessary as an exceptional measure, such

relocation shall take place only with their free and informed consent. Where

their consent cannot be obtained, such relocation shall take place only

following appropriate procedures established by national laws and

regulations, including public inquiries where appropriate, which provide the

opportunity for effective representation of the peoples concerned. 3. Whenever possible, these

peoples shall have the right to return to their traditional lands, as soon as

the grounds for relocation cease to exist. 4. When such return is not

possible, as determined by agreement or, in the absence of such agreement,

through appropriate procedures, these peoples shall be provided in all

possible cases with lands of quality and legal status at least equal to that

of the lands previously occupied by them, suitable to provide for their

present needs and future development. Where the peoples concerned express a

preference for compensation in money or in kind, they shall be so compensated

under appropriate guarantees. 5. Persons thus relocated shall

be fully compensated for any resulting loss or injury. Article 17 1. Procedures established by

the peoples concerned for the transmission of land rights among members of

these peoples shall be respected. 2. The peoples concerned shall

be consulted whenever consideration is being given to their capacity to

alienate their lands or otherwise transmit their rights outside their own

community. 3. Persons not belonging to

these peoples shall be prevented from taking advantage of their customs or of

lack of understanding of the laws on the part of their members to secure the

ownership, possession or use of land belonging to them. Article 18 Adequate penalties shall be

established by law for unauthorised intrusion upon, or use of, the lands of

the peoples concerned, and governments shall take measures to prevent such

offences. Article 19 National agrarian programmes

shall secure to the peoples concerned treatment equivalent to that accorded

to other sectors of the population with regard to: (a) The provision of more land

for these peoples when they have not the area necessary for providing the

essentials of a normal existence, or for any possible increase in their

numbers; (b) The provision of the means

required to promote the development of the lands which these peoples already

possess. 附錄2:二十一世紀議程[64] 23 (2): ...in the more specific

context of environment and development, the need for new forms of participation

has emerged. This includes the need of individuals, groups and organizations

to participate in environmental impact assessment procedures and to know

about and participate in decisions... [They]... should have access to

information relevant on environment and development held by national

authorities, including information on products and activities that have or

are likely to have a significant impact on the environment, and information

on environmental protection measures. 26.1: "Indigenous people

and their communities have an historical relationship with their lands and

are generally descendants of the original inhabitants of such lands. In

the context of this chapter the term "lands" is understood to

include the environment of the areas which the people concerned traditionally

occupy...They have developed over many generations a holistic traditional

scientific knowledge of their lands, natural resources and environment. Their

ability to participate fully in sustainable development practices on their

lands has tended to be limited as a result of factors of an economic, social

and historical nature. In view of the interrelationship between the

natural environment and its sustainable development and the cultural, social,

economic and physical well-being of indigenous people, national and

international efforts to implement environmentally sound and sustainable

development should recognize, accommodate, promote and strengthen the role of

indigenous people and their communities. 26.2: Some of the goals

inherent in the objectives and activities of this programme area are already

contained in such international legal instruments as the ILO Indigenous and

Tribal Peoples Convention (No. 169) and are being incorporated into the draft

universal declaration on indigenous rights, being prepared by the United

Nations working group on indigenous populations. The International Year for

the World's Indigenous People (1993), proclaimed by the General Assembly in

its resolution 45/164 of 18/December/1990, presents a timely opportunity to

mobilize further international technical and financial cooperation. Objectives 26.3: In full partnership with

indigenous people and their communities, Governments and, where appropriate,

intergovernmental organizations should aim at fulfilling the following

objectives: (a) Establishment of a process

to empower indigenous people and their communities through measures that

include: (i) Adoption or strengthening

of appropriate policies and/or legal instruments at the national level; (ii) Recognition that the lands

of indigenous people and their communities should be protected from

activities that are environmentally unsound or that the indigenous people

concerned consider to be socially and culturally inappropriate; (iii) Recognition of their

values, traditional knowledge and resource management practices with a view

to promoting environmentally sound and sustainable development; (iv) Recognition that

traditional and direct dependence on renewable resources and ecosystems,

including sustainable harvesting, continues to be essential to the cultural,

economic and physical well-being of indigenous people and their communities; (v) Development and

strengthening of national dispute-resolution arrangementsin relation to

settlement of land and resource-management concerns; (vi) Support for alternative

environmentally sound means of production to ensure a range of choices on how

to improve their quality of life so that they effectively participate in

sustainable development; (vii) Enhancement of

capacity-building for indigenous communities, based on the adaptation and

exchange of traditional experience, knowledge and resource-management

practices, to ensure their sustainable development; (b) Establishment, where

appropriate, of arrangements to strengthen the active participation of

indigenous people and their communities in the national formulation of

policies, laws and programmes relating to resource management and other

development processes that may affect them, and their initiation of proposals

for such policies and programmes; (c) Involvement of indigenous

people and their communities at the national and local levels in resource

management and conservation strategies and other relevant programmes

established to support and review sustainable development strategies, such as

those suggested in other programme areas of Agenda 21. Activities 26.4: Some indigenous people

and their communities may require, in accordance with national legislation,

greater control over their lands, self-management of their resources,

participation in development decisions affecting them, including, where

appropriate, participation in the establishment or management of protected

areas. The following are some of the specific measures which

Governments could take: (a) Consider the ratification

and application of existing international conventions relevant to indigenous

people and their communities (where not yet done) and provide support for the

adoption by the General Assembly of a declaration on indigenous rights; (b) Adopt or strengthen

appropriate policies and/or legal instruments that will protect indigenous

intellectual and cultural property and the right to preserve customary and

administrative systems and practices. 26.5: United Nations

organizations and other international development and finance organizations

and Governments should, drawing on the active participation of indigenous

people and their communities, as appropriate, take the following measures,

inter alia, to incorporate their values, views and knowledge, including the

unique contribution of indigenous women, in resource management and other

policies and programmes that may affect them: (a) Appoint a special focal

point within each international organization, and organize annual inter-organizational

coordination meetings in consultation with Governments and indigenous

organizations, as appropriate, and develop a procedure within and between

operational agencies for assisting Governments in ensuring the coherent and

coordinated incorporation of the views of indigenous people in the design and

implementation of policies and programmes. Under this procedure, indigenous

people and their communities should be informed and consulted and allowed to

participate in national decision-making, in particular regarding regional and

international cooperative efforts. In addition, these policies and programmes

should take fully into account strategies based on local indigenous

initiatives; (b) Provide technical and

financial assistance for capacity-building programmes to support the

sustainable self-development of indigenous people and their communities; (c) Strengthen research and

education programmes aimed at: (i) Achieving a better

understanding of indigenous people's knowledge and management experience related

to the environment, and applying this to contemporary development challenges;

(ii) Increasing the efficiency

of indigenous people's resource management systems, for example, by promoting

the adaptation and dissemination of suitable technological innovations; (d) Contribute to the endeavors

of indigenous people and their communities in resource management and

conservation strategies (such as those that may be developed under

appropriate projects funded through the Global Environment Facility and the

Tropical Forestry Action Plan) and other programme areas of Agenda 21,

including programmes to collect, analyze and use data and other information

in support of sustainable development projects. 26.6: Governments, in full partnership

with indigenous people and their communities should, where appropriate: (a) Develop or strengthen

national arrangements to consult with indigenous people and their communities

with a view to reflecting their needs and incorporating their values and

traditional and other knowledge and practices in national policies and

programmes in the field of natural resource management and conservation and

other development programmes affecting them; (b) Cooperate at the regional

level, where appropriate, to address common indigenous issues with a view to

recognizing and strengthening their participation in sustainable

development." 附錄3:原住民族權利宣言[65] Article 25: Indigenous peoples

have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual and

material relationship with the lands, territories, waters and coastal seas

and other resources which they have traditionally owned or otherwise occupied

or used, and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this

regard. States shall take effective

measures to ensure that no storage or disposal of hazardous materials shall

take place in the lands and territories of indigenous peoples. States shall also take

effective measures to ensure, as needed, that programmes for monitoring,

maintaining and restoring the health of indigenous peoples, as developed and

implemented by the peoples affected by such materials, are duly implemented. They have the right to special

measures to control, develop and protect their sciences, technologies and

cultural manifestations, including human and other genetic resources, seeds,

medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions,

literatures, designs and visual and performing arts. 附錄4:美洲原住民族權利宣言草案[66] Article 13: Right to

environmental protection 1. Indigenous peoples have the

right to a safe and healthy environment, which is an essential condition for

the enjoyment of the right to life and collective well-being. 2. Indigenous peoples have the

right to be informed of measures which will affect their environment,

including information that ensures their effective participation in actions

and policies that might affect it. 3. Indigenous peoples shall

have the right to conserve, restore and protect their environment, and the

productive capacity of their lands, territories and resources. 4. Indigenous peoples have the

right to participate fully in formulating, planning, managing and applying

governmental programmes of conservation of their lands, territories and

resources. 5. Indigenous peoples have the

right to assistance from their states for purposes of environmental

protection, and may receive assistance from international organizations. 6. The states shall prohibit

and punish, and shall impede jointly with the indigenous peoples, the

introduction, abandonment, or deposit of radioactive materials or residues,

toxic substances and garbage in contravention of legal provisions; as well as

the production, introduction, transportation, possession or use of chemical,

biological and nuclear weapons in indigenous areas. 7. When a State declares an

indigenous territory as protected area, any lands, territories and resources

under potential or actual claim by indigenous peoples, conservation areas

shall not be subject to any natural resource development without the informed

consent and participation of the peoples concerned. 附錄5:拉丁美洲國家憲法中的原住民族資源權條款[67] 阿根廷憲法(Constitución de la Nación Argentina, 1994) Capítulo Cuarto, Atribuciones

del Congreso Art. 41: Todos los habitantes

gozan del derecho a un ambiente sano, equilibrado, apto para el desarrollo humano

y para que las actividades productivas satisfagan las necesidades presentes

sin comprometer las de las generaciones futuras, y tienen el deber de

preservarlo. El daño ambiental generará prioritáriamente la obligación

de recomponer, según lo establezca la ley. Las autoridades proveerán a la

protección de este derecho, a la utilización racional de los recursos

naturales, a la preservación del patrimonio natural y cultural y de la

diversidad biológica, y a la información y educación ambientales. Corresponde

a la Nación dictar las normas que contengan los presupuestos mínimos de

protección, y a las provincias, las necesarias para complementarias, sin que

aquellas alteren las jurisdicciones locales. Se prohibe el ingreso al

territorio nacional de residuos actual o potencialmente peligrosos, y de los

radiactivos. Art. 75 (17): Garantizar el

respeto a su identidad [indígenas argentinos]... Asegurar su participación en

la gestión referida a sus recursos naturales y a los demás intereses que los

afecten. Las provincias pueden ejerecer concurrentemente estas

atribuciones. 玻利維亞憲法(Constitución de Bolivia de 1994) Art. 171 (1): Se reconocen,

respetan y protegen en el marco de la ley, los derechos sociales, económicos

y culturales de los pueblos indígenas que habitan en el Territorio Nacional,

especialmente los relativos a sus tierras comunitarias de origen,

garantizando el uso y aprovechamiento sostenible de los recursos naturales,

su identidad, valores, lenguas, costumbres e instituciones. 巴西憲法(Constitución de la República de Paraguay, 1992) Art. 225: Todos têm direito ao

meio ambiente ecologicamente equilibrado, bem de uso comum do povo e

essencial à sadia qualidade de vida, impondo-se ao poder público e à

coletivadade o dever de defendê-lo e preservá-lo as presentes e futuras

gerações. Art. 231.3 : O aproveitamento

dos recursos hídricos, incluídos os potenciais energéticos, a pesquisa e a

lavra das riquezas minerais em terras indígenas só podem ser efetivados com

autorização do Congresso Nacional, ouvidas as comunidades afetadas,

ficando-lhes assegurada participacao nos resultado de lavra, na forma da lei 哥倫比亞憲法(Constitutión Política de Colombia, 1991 con

reforma de 1997) Art. 63: Los bienes de uso

público, los parques naturales, las tierras comunales de grupos étnicos, las

tierras de resguardo, el patrimonio arqueológico de la Nación y los demás

bienes que determine la ley son inalienables, imprescriptibles e

inembargables. Art. 79: Todas las personas

tienen derecho a gozar de un ambiente sano. La ley garantizará a la

participación de la comunidad en las decisiones que puedan afectarlo. El

deber del Estado proteger la diversidad e integridad del ambiente, conservar

las areas de especial importancia ecológica y fomentar la educación para el

logro de estos fines. Art. 80: El Estado planificará

el manejo y aprovechamiento de los recursos naturales, para garantizar su

desarrollo sostenible, su conservación, restauración o susticución. Además

deberá prevenir y controlar los factores de deterioro ambiental, imponer las

sanciones legales y exigir la reparación de los daños causados. Así mismo,

cooperará con otras naciones en la protección de los exosistemas situados en

las zonas fronterizas. Art. 287: Las entidades

territoriales gozan de autonomía para la gestión de sus intereses y dentro de

los límites de la Constitución y de la ley. En tal virtud tendrán los

siguientes derechos: ... 1. Gobernarse por autoridades

propias. 2. Ejercer las competencias que

les correspondan. 3. Administrar los recursos,

establecer los tributos necesarios para el cumplimiento de sus funciones. Art. 330: De conformidad con la

Constitución y las leyes los territorios indígenas estarán gobernados por

consejos conformados y reglamentados según los usos y costumbres de sus

comunidades y ejercerán las siguientes funciones: 1. Velar por la aplicación de

las normas legales sobre usos del suelo y poblamiento de sus territorios. 2. Diseñar las políticas y los

planes y programas de desarrollo económico y social dentro de su territorio,

en armonía con el Plan Nacional de Desarrollo. 3. Proveer las inversiones

públicas en sus territorios y velar por su debida ejecución. 4. Percibir y distribuir sus

recursos. 5. Velar por la preservación de

los recursos naturales. 9. Las que señale la Constitución

y la Ley. Parágrafo. La explotación de

los recursos naturales en los territorios indígenas se hará sin desmedro de

la integridad cultural, social y económica de las comunidades indígenas.

En las decisiones que se adopten respeto de dicha explotación, el

Gobierno propiciará la participación de los representantes de las respectivas

comunidades." 厄瓜多爾憲法(Constitución Política de la República del Ecuador,

1998) Sección VI Del Medio Ambiente Art. 44. El Estado protege el

derecho de la población a vivir en un medio ambiente sano y ecológicamente

equilibrado, que garantice un desarrollo sostenible. Se declará de interés

público y se regulará conforme a la Ley: a. La preservación del media

ambiente, la conservación de los ecosistemas, la biodiversidad y la

integridad del patrimonio genético del país; b. La prevención de la

contaminación ambiental, la explotación sustentable de los recursos naturales

y los requisitos que deban cumplir las actividades públicas o privadas que

puedan afectar al medio ambiente; y, c. El establecimiento de un

sistema de áreas naturales protegidas y el control del turismo receptivo y

ecológico. Art. 45: Se prohibe la

fabricación, importación, tenencia y uso de armas químicas, biológicas y

nucleares, así como la introducción al territorio nacional de residuos

nucleares y desechos tóxicos. Art. 46: La Ley tipificará las

infracciones y regulará los procedimientos para establecer las

responsabilidades administrativas, civiles y penales, que correspondan a las

personas naturales o jurídicas, nacionales o extranjeras, por las acciones u

omisiones en contra de las normas de protección al medio ambiente. Art. 47: El Estado ecuatoriano

será responsable por los daños ambientales en los términos señalados en el

artículo 23 de la Constitución. Art. 48: Sin Perjuicios de los

derechos de los ofendidos y los perjudicados, cualquier persona natural o

jurídica podrá ejercer las acciones contempladas en la Ley para la protección

del medio ambiente. 墨西哥憲法(Constitutión Política de los Estados Unidos

Mexicanos de 1917 con Reformas de 1998) Art. 4: La ley protegerá y

promoverá el desarrollo de sus... recursos y formas específicas de

organización social... En los juicios y procedimientos agrarios en que

aquellos sean parte, se tomarán en cuenta sus practicas y costumbres

jurídicas en los terminos que establezca la ley. 尼加拉瓜憲法(Constitution of Nicaragua, 1987) Art. 89: El Estado reconoce las

formas comunales de propiedad de las tierras de las Comunidades de la Costa

Atlántica. Igualmente reconoce el goce, uso y disfrute de las aguas y bosques

de sus tierras comunales. 巴拉圭憲法(Constitución de la República de Paraguay, 1992) Art. 7: Del derecho a un

ambiente saludable Toda persona tiene derecho a

habitar en un ambiente saludable y ecológicamente equilibrado. Constituyen

objetivos prioritarios de interés social la preservación, la conservación, la

recomposición y el mejoramiento del ambiente, así como su conciliación con el

desarrollo humano integral. Estos propósitos orientarán la legislación y la

política gubernamental pertinente. Art. 8: De la protección

ambiental Las actividades susceptibles de

producir alteración ambiental serán reguladas por la ley. Asimismo, ésta

podrá restringir o prohibir aquellas que califique peligrosas. Se prohibe la

fabricación, el montaje, la importación, la comercialización, la posesión o

el uso de armas nucleares, químicas y biológicas, así como la introducción al

país de residuos tóxicos. La ley podrá extender ésta prohibición a otros

elementos peligrosos; asimismo, regulará el tráfico de recursos genéticos y

de su tecnología, precautelando los intereses nacionales. El delito

ecológico será definido y sancionado por la ley. Todo daño al ambiente

importará la obligación de recomponer e indemnizar. Art. 65: Del Derecho a la

Participación: Se garantiza a los pueblos indígenas el derecho a participar

en la vida económica, social, política y cultural del país, de acuerdo con

sus uso consuetudinarios, esta Consitución y las leyes nacionales. Art. 66: De la Educación y la

Asistencia: ...Se atenderá, además, a sus defensa contra la regresión

demográfica, la depredución de su habitat, la contaminación ambiental, la

explotación económica y la alienación cultural. 祕魯憲法(Constitución Política del Perú, 1993) Art. 68: El Estado está

obligado a promover la conservación de la diversidad biológica y de las áreas

naturales protegidas. Art. 69: El Estado promueve el

desarrollo sostenible de la Amazonia con una legislación adecuada.

相關國際規約、決議、宣言、以及報告 『聯合國憲章』United Nations

Charter, 1945。 『世界人權宣言』Universal

Declaration of Human Rights, 1948。 『原住暨部落人口公約』Convention

Concerning the Protection and Integration of Indigenous and Other Tribal and

Semi-Tribal Populations in Independent Countries, 1957,簡稱ILO Convention 107。 『國際公民暨政治權公約』International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966。 『國際經濟、社會、暨文化權公約』International Covenant on Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights, 1966。 〈人類環境之問題〉“Problems

of the Human Environment,” UN General Assembly Resolutions

2398 (XXIII), 1968。 『斯德哥摩宣言』Stockholm Declaration, 1972。 『非洲人權憲章』African Charter on

Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1981。 『世界自然憲章』World Charter for

Nature, 1982。 『我們的共同未來』Our Common Future,

1987,又稱為Brundtland

Commission Report、或是Brundtland Report。 『美洲社會、經濟、暨文化權規約附加議定書』Additional Protocol

to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic, Social

And Cultural Rights, 1988,又稱為『美洲公約之聖薩爾瓦多議定書』San Salvador

Protocol to the American Convention。 『原住暨部落民族公約』Convention Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in

Independent Countries, 1989,簡稱為ILO Convention 169。 『里約熱內盧環境暨發展宣言』Rio Declaration on Environment and Development,

1992。 『二十一世紀議程』Agenda 21, 1992。 『原住民族權利宣言』United

Nations Draft Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 1993。 『生物多樣性條約』Convention

Biological Diversity, 1994。 『人權與環境之原則草案』Draft Principles on

Human Rights and the Environment, 1994。 『美洲原住民族權利宣言草案』Proposed American

Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 1997。 『奧胡斯公約』Convention on Access to Information,

Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in

Environmental Matters, 1998,簡稱Aarhus

Convention。

參考文獻 紀駿傑。2006。〈環境正義〉收於生物多樣性人才培育先導型計畫推動辦公室(編)《生物多樣性──社會經濟篇》頁31-48。台北:教育部。 民進黨中央黨部政策委員會。2006。〈民進黨憲改草案〉收於《台灣憲政的困境與重生──總統制與內閣制的抉擇》(研討會論文集)頁72-107。台北:民進黨中央黨部政策委員會。 施正鋒。2006。〈各國憲法中的原住民族條款〉。發表於行政院原住民族委員會主辦、美化環境基金會承辦「國中有國──憲法原住民族專章學術研討會」,台北,11月18日。 施正鋒。2005。《台灣原住民族政治與政策》。台中:新新台灣文化教育基金會/台北:翰蘆圖書出版公司。 台聯政策會。2006。〈台灣憲法草案〉收於台灣團結聯盟(編)《台灣憲法》頁11-36。台北:台灣團結聯盟。 吳珮瑛。2006。〈綜觀台灣自然保育區的經濟效益評估──氣候變遷下潛在損害的可能來源〉《全球變遷通訊》50期,頁31-48。 吳珮瑛、蘇明達。2003。〈生物多樣性資源價值之哲學關係與總價值之內涵──抽象的規範或行動的基石〉《經社法制論叢》31期,頁209-42。 吳珮瑛、蘇明達。2001。《六十億元的由來──墾丁國家公園資源經濟價值評估》。台北:前衛出版社。 21世紀憲改聯盟。2006。《憲法──21世紀憲改聯盟憲改版本》(第二版)。台北:21世紀憲改聯盟。 Acevedo,

Mariana T. 2000. “The Intersection of Human Rights and Environmental

Protection in the European Court of Human Rights.” New York

University Environmental Law Journal, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 437-496. Alston,

Philip. 2001a. “Introduction,” in Philip Alston, ed. Peoples’

Rights, pp. 1-6. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Alston,

Philip. 2001b. “Peoples’ Rights: Their Rise and Fall,” in Philip

Alston, ed. Peoples’ Rights, pp. 259-93. Oxford: Oxford

University Press. Anaya,

S. James. 2005. “Indigenous Peoples’ Participatory Rights in

Relation to Decisions about Natural Resource Extraction: The More Fundamental

Issue of What Rights Indigenous Peoples Have in Land and Resources.” Arizona

Journal of International and Comparative Law, Vol. 22, No. 1, pp. 7-17. Anaya,

S. James. 2004. Indigenous Peoples in International Law, 2nd

ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Anaya,

S. James. 1999-2000. “Environmentalism, Human Rights and

Indigenous Peoples: A Tale of Converging and Diverging Interests.” Buffalo

Environmental Law Journal, Vol. 7, pp. 1-13. Anaya,

S. James, and Robert A. Williams, Jr. 2001. “The Protection of

Indigenous Peoples’ Rights over Lands and Natural Resources under the

Inter-American Human Rights System.” Harvard Human Rights Journal, Vol. 14 (http://www.law.harvard.edu/

students/orgs/hrj/iss14/williams.shtml). Anderson, Michael R. 1996. “Human Rights Approaches

to Environmental Protection: An Overview,” in Alan Boyle, and Michael

Anderson, eds. Human Rights Approaches to Environmental Protection,

pp. 1-23. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Baehr,

Peter R. 1999. Human Rights: Universality in Practice.

Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave. Cohan,

John Alan. 2001-2002. “Environmental Rights of Indigenous Peoples

under the Alien Tort Claims Act, the Public Trust Doctrine and Corporate

Ethics, and Environmental Dispute Resolution.” UCLA Journal of

Environmental Law and Policy, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 133-85. Crawford,

James, ed. 1988. The Rights of Peoples. Oxford:

Clarendon Press. Curry,

Patrick. 2006. Ecological Ethnics: An Introduction.

Cambridge: Polity Press. Dalton,

Jennifer E. 2005. “International Law ad the Right of Indigenous

Self-Determination: Should International Norms Be Replicated in the Canadian

Context?” Queen’s Institute for Intergovernmental Relations Working Paper,

No. 1 (http://papers.ssrn.com/so13/papers.cfm?abstract_id=932467). Dias,

Ayesha. 2000. “Human Rights, Environment and Development: With

Special Emphasis on Corporate Accountability.” Human Development Report

2000 Background Paper (http://www.undp.org/docs/publications/background_papers/Dia2000.

html). Donnelly,

Jack. 1989. Universal of Human Rights in Theory and Practice.

Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Ebbesson,

Jonas. 2002. “Information, Participation and Access to Justice:

The Model of the Aarus Convention.” Paper prepared for the Joint

UNEDP-OHCHR Expert Seminar on Human Rights and the Environment, Geneva,

January 14-16 (http://www.unhchr.ch/

environment/bp5.html). Eckstein,

Gabriel, and Miriam Gitlin. 1995. “Human Rights and

Environmentalism: Forging Common Ground.” Human Rights Brief,

Vol. 2, No. 3 (http://www.wcl.

american.edu/hrbrief/v2i3/enviro23.htm). Ercmann,

Sevine. 1999-2000. “Linking Human Rights, Rights of Indigenous

People and the Environment.” Buffalo Environmental Law Journal, Vol.

15, Nos. 1-2, pp. 15-46. Fabra,

Adriana. 2002. “The Intersection of Human Rights and

Environmental Issues: A Review of Institutional Development at the

International Level.” Paper prepared for the Joint UNEDP-OHCHR Expert

Seminar on Human Rights and the Environment, Geneva, January 14-16 (http://www.unhchr.ch/environment/bp3.html). Gibbs,

Meredith. 2005. “The Right to Development and Indigenous Peoples:

Lessons from New Zealand.” World Development, Vol. 33, No. 8, pp. 1365-78. Hill, Barry E., Steve Wolfson, and Nicholas

Targ. 2004. “Human Rights and the Environment: A Synopsis

and Some Prediction.” Georgetown International Environmental Law Review, Vol.

16, No. 3 (http://findarticles.com/p/articles/

mi_qa3970/is_200404/ai_n9406153) Hiskes,

Richard P. 2005. “The Right to a Green Future: Human Rights,

Environmentalism, and Intergenerational Justice.” Human Rights

Quarterly, Vol. 27, No, 4, pp. 1347-64. Kastrup,

Jose Paulo. 1997. “The Internationalization of Indigenous Rights

from the Environmental and Human Rights Perspective.” Texas International

Law Journal, Vol. 32, No. 1

(http://www.law-lib.utoronto.ca/Diana/fulltext/kast.htm). Kiss,

Alexander. 1992. “An Introductory Note on a Human Right to

Environment,” in Edith Brown Weiss, ed. Environmental Change and

International law: New Challenges and Dimension. Tokyo: United

Nations University Press (http://www.unu.

edu/unupress/unupbooks/uu25ee/uu25ee0k.htm). Kolari, Tuula,

2004. The Right to a Decent Environment with Special Reference to

Indigenous Peoples. Rovaniemi, Finland: Northern Institute for

Environmental and Minority Law, University of Lapland. Manus, Peter.

2006. “Indigenous Peoples’ Environmental Rights: Evolving Common Law

Perspectives in Canada, Australia, and the United States.” British

Columbia Environmental Affairs Law Review, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 1-86. Morales, M. C.

n.d. “The Philosophy of the UNESCO towards’ Intellectual and Moral

Solidarity.” (pdf) O’Connor, Thomas

S. 1994. “’We Are Part of Nature’: Indigenous Peoples’ Rights as

a Basis for Environmental Protection in the Amazon Basin.” Colorado

Journal of International Environmental Law and Policy, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp.

193-211. Pathak,

R. S. 1992. “The Human Rights System as a Conceptual Framework

for Environmental Law,” in Edith Brown Weiss, ed. Environmental

Change and International law: New Challenges and Dimension. Tokyo:

United Nations University Press (http://www.unu.edu/unupress/unupbooks/uu25ee/uu25ee0k.htm). Pevato,

Paula M. 1999. “A Right to International Law: Current Status and

Future Outlook.” Review of European Community and International Law,

Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 309-21. Purdon,

Catherine. 2006. “Human Rights and the Environment: At the

Crossroads.” Jurisprudence (http://international.jurisprudence.cz/clanek.html?id=11&seznamtyp=

&rocnik=&cislo=). Shelton,

Dinah. 2002. “Human Rights and Environment Issues in Multilateral

Treaties Adopted between 1991 and 2001.” Paper prepared for the Joint UNEDP-OHCHR

Expert Seminar on Human Rights and the Environment, Geneva, January 14-16 (http://www.unhchr.ch/

environment/bp1.html). Shelton,

Dinah. 2001. “Environmental Rights,” in Philip Alston, ed. Peoples’

Rights, pp. 185-258. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Shelton,

Dinah. 1991-1992. “Human Rights, Environmental Rights, and the

Right to Environment.” Stanford Journal of International Law, Vol. 28,

No. 1, pp. 103-38. Shutkin, William

Andrew. 1990-1991. “International Human Rights Law and the Earth:

The Protection of Indigenous Peoples and the Environment.” Virginia

Journal of International Law, Vol. 31, No. 3, pp. 479-511. Stavropoulou,

Maria. 1994. “Indigenous Peoples Displaced from Their

Environment: Is There Adequate Protection?” Colorado Journal of

International Environmental Law and Policy, Vol. 5, pp. 105-25. Tamayo, Ann Loreto,

ed. 2003. Indigenous Peoples and the World Summit on

Sustainable Development (WSSD). Baguio City, The Philippines:

Tebtebba Foundation. Tauli-Corpuz,

Victoria, and Joji Carino, eds. 2004. Reclaiming Balance:

Indigenous Peoples, Conflict Resolution and Sustainable Development.

Baguio City, The Philippines: Tebtebba Foundation. Watters, Lawrence,

ed. 2004. Indigenous Peoples, the Environment and Law.

Durham, N.C.: Carolina Academic Press. Watters,

Lawrence. 2001-2002. “Indigenous Peoples and the Environment:

Convergence from a Nordic Perspective.” UCLA Journal of Environmental Law

and Policy, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 237-304.

* 發表於台灣原住民文教基金會主辦「生物多樣性與原住民族權益研討會」,台北,2006/11/3。 [1] 有關人權的一般性理論,見Baehr(1999)、以及Donnelly(1989)。 [2] 有關於原住民族權利的介紹,見Anaya(2004)。 [3] 廣義來看,就是要有「過得去」(decent)、「健康的」(healthy)、還是「安全的」環境;狹義來看,就是指乾淨的空氣、水、以及土壤;見Hiskes(2005: 1352)。 [4] Vasak認為這三代人權恰好與法國大革命所揭櫫的自由、平等、博愛相符;見Morales(n.d.)、以及Pathak(1992)的討論。 [5] 公民權又稱為「公民自由」(civil liberties),是指自由、生命、財產、宗教、言論、以及結社的權利。 [6] Alston(2001a: 2)稱之為「peoples’ rights」,Crawford(1988)稱之為「rights of peoples」;一般而言,第三代人權/共同權包括發展權、環境權、以及和平權(Baehr, 1999: 6;

Donnelly, 1989: 143-45; Pathak, 1992)。有關於第三代人權的發展,見Alston(2001b),特別是頁264-68。 [7] 有關於原住民族權是否算是一種三代人權,見Mary Ellen Turpel(Dalton, 2005: 1-2);Alston(2001)認為是理所當然、而未加論述。 [8] “Problems of the

Human Environment,” UN General Assembly Resolutions

2398 (XXIII)。 [9] United Nations Conference on the Human Environment。 [10] Stockholm Declaration。 [11] Organization of

African Unity,簡稱為OAU。 [12] African Charter

on Human and Peoples’ Rights, 1981。 [13] Organization of

American States,簡稱為OAS。 [14] Additional

Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights in the Area of Economic,

Social And Cultural Rights, 1988,又稱為『美洲公約之聖薩爾瓦多議定書』(San Salvador Protocol to the

American Convention)。 [15] International Labor

Organization,簡稱為ILO。 [16] Convention Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in

Independent Countries, 1989,簡稱為ILO Convention 169。 [17] United Nations Conference on Environment and Development,簡稱為UNCED;又稱為「地球高峰會議」(Earth

Summit)。 [18] Rio Declaration

on Environment and Development。 [19] Agenda 21。 [20] 不管稱為interdependence、interrelationship、connection、convergence、intersection、link、linkage、nexus、overlapping、還是relationship。 [21] 當然,還有一種可能,也就是兩者相同(重疊);不過,如果兩者所指涉的內容相同,就沒有必要多此一舉、另外再取一個名字。 [22] Acevedo(2000: 452)的用字是「必要的先決條件」(necessary

prerequisite);Shelton(2001: 231)的用字是「先決條件」(precondition)。 [23] Environmental

entitlements;這是Fabra(2002: 18)的用語。 [24] 有關環境正義的討論,見Curry(2006)、Hiskes(2005)、以及紀駿傑(2006)。 [25] 然而,由於環境權是衍生而來的,也有人認為這是次級的人權,不像生命權那麼不可缺少;見Hiskes(2005: 1348)。 [26] 不過,有些支持實質環境權的人擔心參與權可能的負面影響,也就是人們可能關心短期的富裕、而非長期的環境保護;見Dias(2000: 8)。 [27] United Nations Draft Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples, 1993。 [28] 『野生動物保育法』(http://law.moj.gov.tw/Scripts/Query4B.asp?FullDoc=所有條文&Lcode=M0040009): 台灣原住民族基於其傳統文化、祭儀,而有獵捕、宰殺或利用野生動物之必要者,不受第十七條第一項、第十八條第一項及第十九條第一項各款規定之限制。 前項獵捕、宰殺或利用野生動物之行為應經主管機關核准,其申請程序、獵捕方式、獵捕動物之種類、數量、獵捕期間、區域及其他應遵循事項之辦法,由中央主管機關會同中央原住民族主管機關定之。 [29] 自然生態保護區包括國家公園、自然保留區、野生動物保護區、野生動物重要棲息環境、以及國有林自然保護區;見吳珮瑛(2006)。 [30] 我們可以看到,財產權與自決權有時可能無法區分,譬如強制遷徙原住民族,來進行開採、建設、或是保育工作。有關遷村與原住民族的環境權,見Stavropoulou(1994)。 [31] 有關於原住民族與國家在永續發展上的衝突,見Tauli-Corpuz與Carino(2004)、以及Watters(2004)。 [32] 在這裡,我們是把原住民族的發展權放在環境權的架構下來討論。當然,也可以將原住民族的發展權當作是另一種共同權來思考;譬如,見Gibbs(2005)。 [33] 譬如吳珮瑛、蘇明達(2001)在評估墾丁國家公園資源價值之際,抽樣的對象除了有全國的民眾以外,還特別考量當地居民的意向。 [34] 站在原住民族的角度來看,這是「大家的」國家、還是「他們/你們」非原住民的國家,仍有很大的考論空間。此時,並非原住民族與國家的定位問題而已,其實是牽涉到多數族群如何與少數族群妥協的問題;參見Pathak(1992)。 [35] 譬如說,究竟熊與原住民族的生存空間,何者為重? [36] 包括這「生命中心倫理」(biocentric ethics、或life-centered ethics)、以及「生態中心倫理」(ecocentric ethics)兩種看法。 [37] 包括Norton「弱的人類中心主義」(1984)(weak anthropocentrism)、以及Murdy(1975)的「現代人類中心主義」(modern anthropocentrism)。前者的修正擴展涵蓋了這一世代對未來世代,在物種資源分享上應盡的責任;後者的修正則納入了「非人類中心主義」倫理觀,認為物種具有的內在價值。 [38] 儘管如此,一些生態主義者還是堅決反對以人權的角度來看生態保護(Shelton, 2001: 188)。 [39] United Nations

Charter, 1945。 [40] Universal

Declaration of Human Rights。 [41] Convention

Concerning the Protection and Integration of Indigenous and Other Tribal and

Semi-Tribal Populations in Independent Countries,簡稱ILO Convention 107。 [42] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights,

1966。 [43] International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural

Rights, 1966。 [44] World Charter

for Nature, 1982。 [45] Hill(2002: 1)將國際環境法分為有約束力(enforceable)的「硬法」(hard law)、以及有道理卻沒有約束力的「軟法」(soft law);前者摡指國際規約,而宣言屬於後者。 [46] UN World Commission

on Environment and Development,簡稱WCED,又稱為Brundtland Commission;成立於1983年。 [47] Our Common

Future,又稱為Brundtland

Commission Report、或是Brundtland Report。 [48] 根據Shelton(2001: 197-98)的說法,有可能是與會人士缺乏人權專家,因而比較沒有法學訓練。另外,各國代表也認為,以人權的觀點來看環境保護,看不出對他們自己的國家有甚麼好處。 [49] Convention

Biological Diversity, 1994。 [50] UN Economic and

Social Council,簡稱ECOSOC。 [51] UN Commission on

Human Rights,簡稱UNCHR,於1946年設立。 [52] Sub-committee on

Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities,於1947年設立;1999年起改名為Sub-committee on the Promotion

and Protection of Human Rights。 [53] Special Rapporteuer

on Human Rights and the Environment。 [54] 前三份報告是分別在1991、1992、以及1993年提出;見Dias(2000: 14-15)。 [55] Draft Principles

on Human Rights and the Environment, 1994。 [56] UN Working Group on

Indigenous Populations,簡稱UNWGIP;成立於1982年。 [57] United Nations Draft Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples。 [58] Inter-American Commission

on Human Rights,簡稱IACHR。 [59] Proposed

American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples。 [60] United Nations

Economic Commission for Europe,簡稱UNECE。 [61] Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation

in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters,簡稱Aarhus Convention;見Ebbesson(2002)、Kolari(2004: 69-75)、以及Shelton(2002)。 [62] 有關於原住民族參與2002年在南非舉行的「世界永續發展高峰會議」(World Summit on

Sustainable Development,簡稱WSSD),見Tamayo(2003)。 [63] http://www.unhchr.ch/html/menu3/b/62.htm。 [64]

http://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/documents/agenda21/english/agenda21toc.htm。 [65]

http://www.unhchr.ch/huridocda/huridoca.nsf/(Symbol)/E.CN.4.SUB.2.RES.1994.45.En?OpenDocument。 [66] www.indianlaw.org/OAS_Briefing_Book1999.pdf。 [67] 整理自http://www.cidh.oas.org/indigenas/indigenas.en.01/articleXIII.htm。 |