|

Pursuing Indigenous Self-Government in Taiwan* |

||

|

Cheng-Feng Shih, Professor** Department of Public Administration

and Institute of Public Policy Tamkang

University, Tamsui, Taiwan |

||

|

Introductions The

12 Indigenous Peoples constitute roughly 2% of the 23,000,000 population of

Taiwan. Before the 2000 presidential election, Chen Sui-bien, candidate of the then opposition party, Democratic

Progressive Party (DPP), signed a “partnership” agreement with leaders of the

Indigenous movement in Taiwan in 1999. The next year, President Chen

signed another agreement with these leaders and reconfirmed his determination

to honor those pledged in the earlier agreement, including promoting

indigenous self-governments. After his reelection in 2004, President

Chen, to the surprise of the Indigenous Peoples, announce that he would put

up an exclusive chapter for the Indigenous Peoples in the much discussed new

constitution in 2006. While Indigenous leaders are endeavoring to draft

such a constitutional bill for themselves, there are concerns that President

Chen is only paying lip service to them. This article will examine what

efforts have been made to arrive at the goal of self-government within the

administration since the DPP came to power in 2000. The focus will be

on comparing the two versions of Indigenous Self-Government Bill,

especially how the notion of “nation-to-nation” is embodied. And then,

we will examine how indigenous intellectuals have reacted to them.

Finally, we will look into what barriers may have arisen on the road to

indigenous self-government.

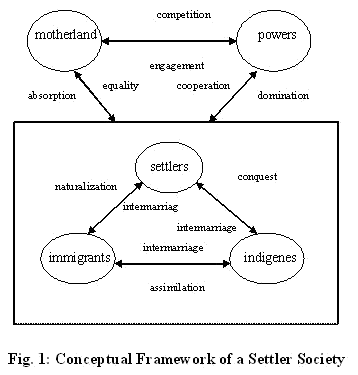

Taiwan

is a settler society like Canada, United States, Australia, and New

Zealand. Before settlers began arriving at the island four centuries

ago, the Indigenous Peoples had resided here since time immemorial. From

discovery, conquest, to settlement by the “others,” they still had gradually

retreated to remote areas or to accept cultural assimilation. The

state, seeking to become a modern nation-state, is playing a two-level game

(Fig. 1): one the one hand, it has to resist forceful absorption by the

motherland, China, and domination by neighboring power; on the other hand, it

has to strike a balance among settlers, indigenes, and later-coming

immigrants. Basically, it is a three-pronged task: state-making in the

sense of securing sovereignty, nation-building in terms of forging common

national identity, and state-building in the process of institutional

engineering.

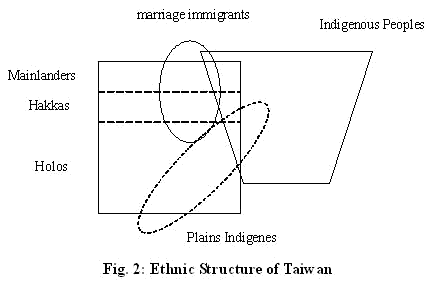

Nowadays,

it is generally agreed that there are four major ethnic groups in Taiwan

(Fig. 2): Indigenous Peoples, Mainlanders, Hakkas,

and Holos. While the former are of

Austronesian stock, the latter three are descendants of those Han

refugees-migrants-settlers of Mongolian race who sailed from China as early

as 400 years ago. Ethnic competitions would be found mainly along three

configurations: Indigenous Peoples vs. Hans (Mainlanders+Hakkas+Holos), Hakkas vs. Holos, and

Mainlanders vs. Natives (Indigenous Peoples+Hakkas+Holos). For the

past two decades, the number of marriage immigrants from Southeast Asian

countries and China has surpassed that of the Indigenous Peoples: yet, it is

not clear whether they would constitute a new ethnic groups

against the natives. Finally, there is a reclaiming collective identity

of Plaines Indigenes, who had almost lost their indigenous characteristics

until the 1930s. In the old days, they had chosen to Sincized themselves and become “human beings” in order to

avoid systemic discrimination. In essence, these are actually Mestizos

who have so far considered themselves Creoles. However, most of

them are not officially recognized as indigenes by the government. Efforts In

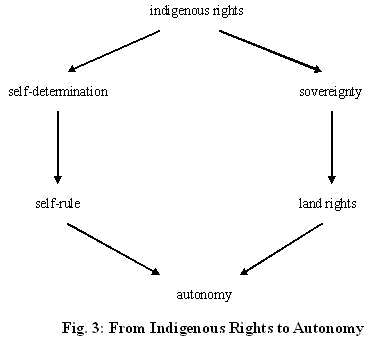

the past two decades, the Indigenous Movement in Taiwan, based on the idea of

inherent indigenous rights, has focused on three interlocked goals: the right

to be indigenes, self-rule, and land rights. Being the Indigenous

Peoples of Taiwan, they claim that they are not merely ethnic minorities but

indigenes that deserve their rights enshrined in international laws. It

is argued that Indigenous Peoples have never renounced their sovereignty

seized by the aliens. Indigenous elites insist that indigenous lands

dispossessed a century ago be returned to the Indigenous Peoples.

Buttressed by the idea of self-determination, they demand the establishment

of self-governments in place of present-day local administrative units.

It is believed that only self-rule without being patronized can lead to true

autonomy where the Indigenous Peoples can decide what is

the best for themselves. To certain degree, the government seems

to realize that protecting indigenous rights is a gesture of reconciliation.

So

far, two versions of the Indigenous Self-Government Bill have been

prepared. Bill A, while excessively detailed in light of Continental

Laws, was drafted by experts on local government and fashioned after the Local

Government Law in the spirit that the authority of the indigenous

government is delegated by the central government. It was then replaced

by Bill B after been stalled during the process of cross-ministry reviews, in

the hope that this simplified version would be a model of procedural law

rather than substantial one for future drafting of separate autonomous

statute, read “treaty,” between each indigenous people and the central

government. Tactically speaking, it was purposefully calculated that

this reduced bill would ease the painstaking process of lawmaking.

However, after some heated deliberations in the Legislature, the government

was forced to withdraw the bill as indigenous legislators complained that no

adequate indigenous rights had been guaranteed in the bill. It was

forcefully insisted that some itemized list of indigenous rights, especially

financial support in certain proportions to the annual national budget, be

specifically recognized in the bill. Otherwise, it was contested that

the bill-in-principle was nothing but an undisguised hoax to deprive the

Indigenous Peoples of what they deserve. The

most fundamental issue raised is whether the idea of indigenous sovereignty

is compatible with the existing state’s indivisible sovereignty. In

other words, it is suspected that how sovereignty is to be shared by the

Indigenous Peoples and the state. It is also doubted whether it would

challenge the territorial integrity of the state if the Indigenous Peoples choose

to exercise their right to self-determination and declare outright

independence. Some even argue that the Indigenous Peoples have never

possessed any right to the lands except the right to exploitation.

Others have gone so far so to dismiss the whole notion of indigenous

rights. Strongest resistances come from the Bureau of Forest Services

and from the Bureau of Water Resources, whose jurisdictions largely overlap

with the designated areas for indigenous self-governments, particularly the

former. While daring not to speak out openly, some DPP elements have suggested that the emperor’s new clothes be thrown

into closet as a responsible ruling party, implying that those promises to

wood the Indigenous Peoples are nothing but empty electoral rhetoric during

presidential campaigns. Engulfed

in the disillusioned clouds, an Indigenous Fundamental Law was

unexpectedly passed by the outgoing legislators in 2005. Praised as the

Indigenous Constitution, the law may be considered as a de facto

treaty between the Indigenous People and the state. Essentially a

synthesis of abstract principles and concrete protections of indigenous

rights, the law designates the formation of an Enacting Committee under the

Executive for its enforcement, where two-thirds of its members be reserved

for the Indigenous Peoples. It also requires

concerned ministries and agencies to revise relevant laws and statutes in its

conformity in three years. Last but not least, it attaches a sting that

there shall be a separate chapter for the Indigenous Peoples in the intended Bill

of Rights. Within

the Council of Indigenous Peoples, a working group made up of ministerial

delegates, indigenous representatives, and scholars, was established in early

2006 to assist further considerations of the abovementioned enacting

committee. Since its inception, its members have been working under

four substantive groups: administration, education-culture,

economics-development, and indigenous lands. While ministerial

delegates are ready to protect their constituencies, indigenous

representatives are similarly eager to defend their inherent rights.

This sometimes leaves scholars as crucial arbitrators when disputes

arise. When those civil servants throw doubts upon, if not ridicule,

the whole idea of indigenous rights, non-indigenous participants qua

scholars have to come up with legitimate rationales upon international laws,

political philosophy, and practices from other countries that lie under the Indigenous

Fundamental Law. From time to time, it is argued without valid

proof that indigenous rights may conflict with national interests and that

therefore their fulfillment be suspended. At

this juncture, scholars have to point out that there is no necessary

contradiction between indigenous rights and national interests; even if there

is, some compensatory measures are warranted. At times, in addition to

professional knowledge, scholars have to work on their conscience while

walking on a thin line between the quarreling parties, so that they would not

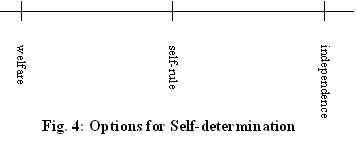

be suspected of being agents of either. IssuesLogically,

there are three plausible options when Indigenous Peoples exercise their

rights to self-determination: to accept assimilation, to maintain

self-government, and to seek independence. A series of alien rulers had

in the past sought at all costs to assimilate Plains Indigenes in western

Taiwan, whose descendants are now almost inextinguishable from

non-indigenes. Only those Indigenous Peoples who have bee geographically segregated in central mountain areas

and eastern Taiwan are lucky enough to retain their cultural

identities. Enlightened by the spirit of multiculturalism, more and

more Indigenous Peoples are proud to express their distinguished

characteristics. Nonetheless, indigenous are still divided over the

rationality of upholding self-governments (Fig. 4).

While

some, for fear of discrimination, suspect the wisdom to resist further

assimilation, some more, judging from the fact that non-indigenous peoples

have only exploitation on their minds, economic development and social

welfare assured by the government are the only guarantee for progress.

In their view, therefore, the abstract principle of self-determination and

the remote goal of self-rule are nothing but futile illusions. On the

extreme of the spectrum, few indigenous elites have claimed that only

political independence can lead to authentic salvation, even though no

serious effort has been made to promote its materialization. As a

result, self-government turns out to be a pragmatic compromise: while

reserving their right for claiming independence, indigenous leaders would see

how the government is willing to prevent indigenous governments from being

empty shells. Meanwhile,

it is believed that guarded by the three-layered protection from the Indigenous

Fundamental Law, the proposed chapter on Indigenous Peoples for the

proposed new Constitution, and a similar one for the Bill of Rights as

pledged by President Chen, indigenous self-rule may enjoy a better

fate. However, since there is no guarantee that the latter two would be

eventually passed by the opposition-dominated Legislature,

they are drafted to include as many indigenous rights as possible stipulated

in the United Nations Draft Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples,

1995. Of course, many doubts and reservations have been raised

within and without the Council of Indigenous Peoples, which is in charge of

the two bills. In

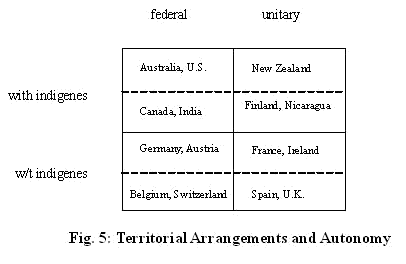

terms of technical feasibility, there is some disagreement over whether a

federal system for central government is the only territorial arrangement

compatible to indigenous self-rule. However, experiments from countries

with and without indigenous peoples have show that

unitary systems may equally serve the purpose of autonomy well (Fig. 5), as

the case of Nicaragua has illustrated.

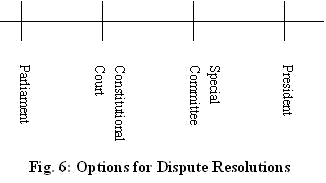

There

are also concerns over which body is going to arbitrate between indigenous

self-governments and central/local governments when disputes arise.

Without any precedent, four options have been suggested: the Parliament, the

Constitutional, a special committee, and the President. Since indigenous

MP’s constitute less than 5% of the Parliament, it is doubtful how this

mechanism, brought into being under the principle of one-man-one-vote, would

be in any position to defend indigenous rights, unless a parliamentary

committee where indigenous MP’s dominate is created. While the

Constitutional Court seems an impartial branch of the central government, it

is still precarious to leave the future of Indigenous Peoples in the hand of

an organ where no indigenous judge would be presiding over the case in the

ten to twenty years. There are suggestions that some kind of special

committee is designed under the President, or the President is responsible to

resolve disputes (Fig. 6). Nonetheless, it is uncertain whether the

President would consider himself/herself as the head of state mandated by the

dominant non-indigenes only, or as a dispassionate arbitrator supported by

the Indigenous Peoples as well. In the end, there is no answer for the

following challenge: “If the relationship between the Indigenous Peoples and

the state is considered as “partnership,” shouldn’t there be an outside third

party to play the role of arbitrator?” This question deserves further

considerations not only among the Indigenous Peoples but also between elites

from indigenous and non-indigenous sectors.

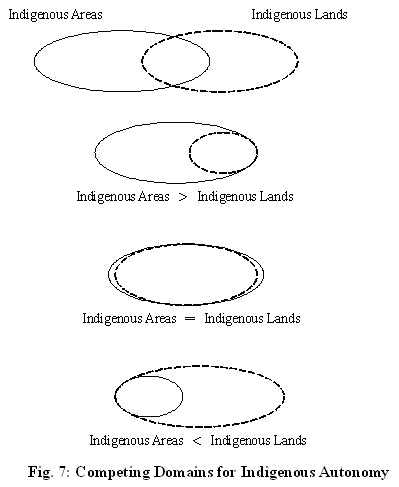

Eventually,

the final battleground is found in the appropriation of lands for indigenous

self-governments. Under Article 2 of the Indigenous Basic Law,

two relevant terms are defined: “Indigenous Areas” means those areas

traditionally occupied by Indigenous Peoples and sanctioned by the Executive,

and “Indigenous Lands” includes traditional lands occupied by the Indigenous

Peoples and current lands nominally reserved for them. Since these two

are conceptually distinct, we may delineate their possible relationships in

terms of Venn Diagrams (Fig. 7). Since

the end of World War II, the government has confined the so-called

“Indigenous Areas” into 55 townships, among which 30 are designated as

“Mountain Indigenous Townships,” and 25 “Plains Indigenous Townships.”

For most ministries and agencies concerned, especially the Bureau of Forest

Services and, to a less degree, the State Park Authorities, this

administrative arrangement is definite without any doubt. In other

words, the “Indigenous Lands” lie within the limits of the “Indigenous

Areas.” This defensive interpretation makes them anxious calculate how

many lands they would be forced to release to Indigenous Peoples in case any

self-governments come into existence. In their contemplation, the best

strategy is to retain the ongoing system of token monetary compensation

without their jurisdictions over indigenous land being taken away. In

the meantime, they also keep close eyes on the proposed mechanisms for

co-management on indigenous lands confiscated for public utilities.

However,

for the Council of Indigenous Peoples, which is currently undertaking surveys

of traditional lands that had once been utilized by the Indigenous Peoples in

the past, there is no reason why the boundaries of these old administrative

units cannot be subject to any adjustments. According to the maps of

traditional territories drawn according to oral narratives so far, some

Indigenous Peoples have claimed that their tribal lands extend beyond the

highly restricted “Indigenous Areas.” Therefore, even though the

so-called “Indigenous Lands” stipulated in the Indigenous Basic Law

have not been designated, they are expected to cover the whole “Indigenous

Areas.” Theoretically

speaking, the whole island used to belong the

Indigenous Peoples. Nonetheless, it is not clear whether they are

descendants of those assimilated Plaines Indigenes. Unless the 12

Indigenous Peoples forge formal alliance with Plaines Indigenes, claims over

the land beyond the “Indigenous Areas” will be strongly resisted. In the

short time, one feasible compromise is to limit land claims to the

“Indigenous Areas,” in the hope that the whole officially designated

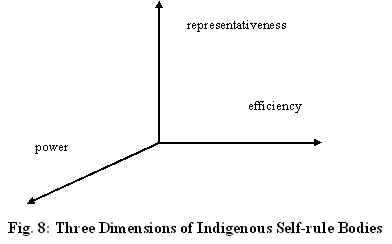

indigenous reserved lands be handed over to indigenous self-governments. Visions For

an indigenous self-government to work effectively with an eye to protect

indigenous rights, three aspects are crucial for meaningful institutional

designs: authority, efficiency, and representativeness (Fig. 8). First

of all, to be truly autonomous, political authority of the indigenous

government must find its place in the Constitution. Otherwise, its

uniqueness as a manifestation of inherent indigenous rights would run the

risk of being compromised, if not nullified, by a legislature dominated by

non-indigenes. Secondly, there are also debates over whether there

shall be one indigenous government only, one self-government for each

Indigenous People, or as many tribal governments as possible. Since not

all Indigenous Peoples are opt for self-rule, at least in the short run, a pan-indigenous

self-government, even a confederation in the loosest sense, seems

impractical. On the other hand, tribal governments appear to be

the best model to express grassroots participation for direct democracy,

caution should be made against low economy of scale.

Finally,

there have be conflicting views over what

institutional arrangements to represent the Indigenous Peoples (Fig.

9). It appears that the goal of sufficient representation may at times

contradict that of efficiency. Ideally, there would be one tribal

council for each tribe with and without self-government. As a result,

depending on the definition of tribe, it is estimated that there would be

roughly 250 tribal councils. While retaining their autonomy, these

tribal councils are expected to forge some forms of coalition along cultural

lines in order to bargain with the government. Depending on different

patterns of tribal organizations, whether scattered or concentrated, these

processes of internal integration warrant some cautious procedures.

Thirdly, there have some suggestions that a second chamber be established in

the national legislative body. This amounts to bestow a right of

minority veto to the Indigenous Peoples. It is not clear if the

‘mainstream” of society is ready to embrace this Lijphartian

consociational mechanism. Finally, indigenous

leaders have persistently put forward to the formation of a pan-indigenous

assembly fashioned after the Assembly of First Nations in Canada. It is

hoped that this representative body may select a grand chief who is co-equal

with the President so that the idea of “nation to nation” relation may be

formally embodied.

ConclusionsThe

author was fortune enough to deliver a speech on indigenes’ constitutional

rights at the first assembly of indigenous leaders in history at Taichung,

Taiwan, on June 28, 2006. At this historical occasion, these tribal

leaders expressed their endorsement for the draft indigenous chapter of the

new constitution. They also declared their determination to take back

their traditional lands. So far, at least one Indigenous Assembly,

formed by the Thao People, a people with a

population less than 1,000, has been recognized by the government, which has

agreed to return a 150-acreage land to this smallest people. Still,

there are not without any setbacks. For instance, in the

aftermath of the downsize of the Parliament after

constitutional amendments in 2005, guaranteed indigenous seats will be

reduced from 8 to 6 in the future. Also, there have been subtle

restrictions on indigenous affirmative actions. They are still strangers on

their own lands. * Prepared for the

International Peace Research Association Biannual Conference “Patters of

Conflict Paths to Peace,” University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada,

June 29-July 3, 2006. ** The author is co-convenor of the Indigenous Working Group for Promoting New

Constitution, Council for Indigenous Peoples. He also serves as

chairman of the Administrative Sub-committee of the Working Group for

Enacting the Indigenous Basic Law, Council for Indigenous Peoples. His

articles in English may be found at http://mail.tku.edu.tw/cfshih/default2.htm.

For correspondence: cfshih@mail.tku.edu.tw. |