|

A Brief Introduction to

Electoral Systems* |

||

|

|

||

|

Dr. Cheng-Feng Shih(施正鋒) Professor, Department of Public Administration

and Institute of Public Policy Tamkang University, Tamsui, Taiwan Electoral

systems are not equivalent to electoral laws; rather, they are mechanisms

that translate votes into seats in legislative as well as executive

elections. That electoral systems matter is testifies by the fact that

parties with the same votes may receive disparate percentages of seats under

different electoral systems. In the Third-Wave of democratization,

electoral engineering has been considered crucial for successful political

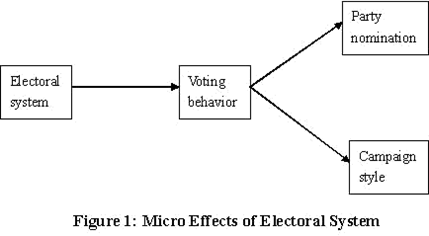

engineering, if not manipulation. Electoral systems have both micro and

macro political consequences. On the one hand, electoral systems, as

political institutions, while directly acting upon voters’ behavior, would

ultimately provide incentives for and barriers to political parties and

candidates in the process of nomination and of campaign (Figure 1). On

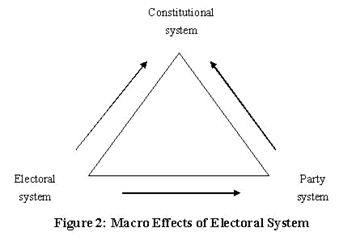

the other hand, electoral systems would produce three systemic effects:

proportionality of the seat in relation to the vote parties receive, the

number of parties, and minority representation. While the former are

termed psychological effects, the later mechanical ones. When electoral

systems and their impacts on the party system are waged against the

constitutional system already adopted, whether they are synchronized will

decide how the political system may operate smoothly (Figure 2).

Political scientists would generally agree that proportional electoral

systems are conducive to multi-party systems, plurality ones to two-party systems,

and majority ones to two-camp systems. As it has been suggested by some

that multi-party systems are incompatible with presidential systems, the

logic goes, either the constitutional system has to shift gear to a

parliamentary one or a non-proportional electoral system has to be devised.

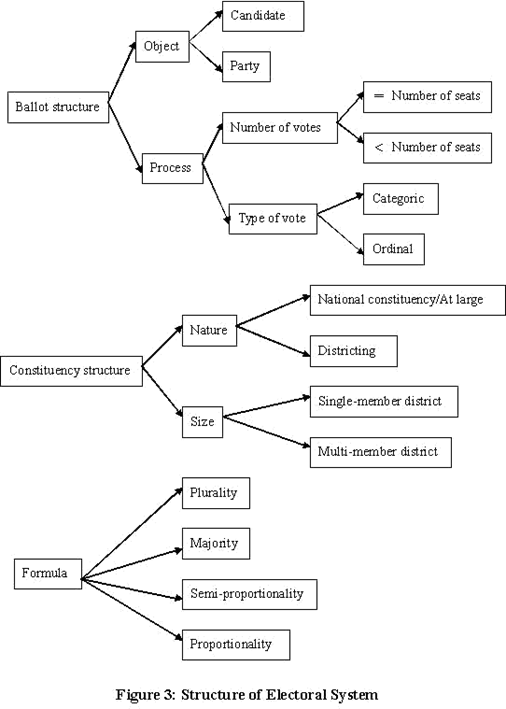

The

structure of electoral systems has three major components: ballot structure,

constituency structure, and translating formula (Figure 3). First of

all, the balloting structure is composed of two dimensions: to whom the vote

goes (candidate or party), and the process of voting, which is in turn

decomposed into the number of votes (equal or smaller than the number of

seats) and the type of vote (categorical or ordinal). Secondly, the

constituency structure has to decide its nature (either at large or

districting), and size (single-member or multi-member district). Last

but not least, we have to choose from among the following translating

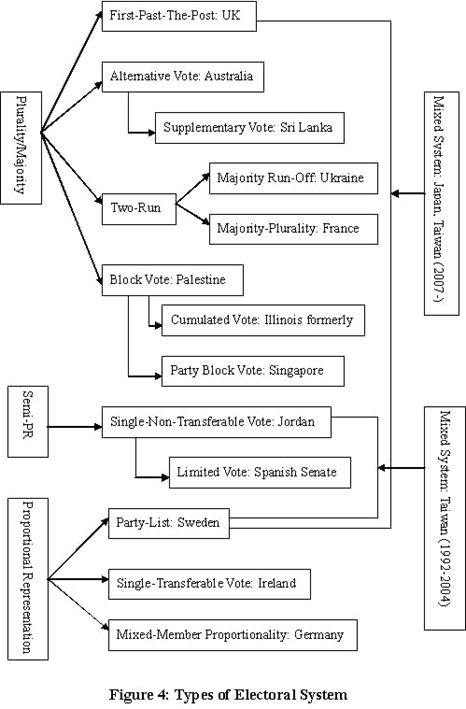

formulae: plurality, majority, semi-proportionality, and proportionality. If

we focus on the translating formula, we can come up with two ideal types of

electoral system, plurality/majority and proportional representation, along

with semi-proportionality and some so-called mixed systems (Figure 4).

Within the plurality camp, first-past-the-post is most popular in countries

under Anglo-Saxon influence while various form of block votes are also

adopted. Under the majority branch, two-run systems are simple but

cumbersome if no candidate receives majority of the votes; alternative votes

appear fairer for voters as they may express their preference for the

candidates while casting their votes. For most of Western and Northern

European countries, they seem satisfied with proportional representation in the

form of party-list even though Ireland enjoys the single-transferable vote

that allows voters to cast ordinal votes. The most amazing proportional

representation system is the mixed-member proportionality system (also termed

additional member system), invented by Germany and imitated by New Zealand,

one that guarantees both representatives’ close contact with their

constituencies and proportionality.

Of

course, we should not leave behind the semi-proportional representation

system that has just been abolished in Taiwan earlier this year but is still

employed by some countries in the Middle East, the single-non-transferable

vote. In the 1990s, we witnessed burgeons of some mixed systems, also

know generically as parallel systems. As the name suggests, they are

designed after assorted combinations of proportional representation and

first-past-the-post constituencies. Compared to the mixed-member

proportionality system mentioned earlier, these mixed systems are only

partially proportional depending on the weight of the proportional

representation. It is noted that the electoral system for legislative

elections since 1992 have be syntheses of single-nontransferable-vote and

proportional representation. Starting from the legislative election in

2007, it will be adjusted to a mixture of first-past-the-post and

proportional representation. If the political science wisdom is

correct, it is expected that the fragmentation and thus the centrifugal

tendency of the party system may be alleviated. As a result, a

popularly elected president can be more accountable to the voters even under

divided government, that is, when the opposition controls the legislative

branch. Finally,

if a country is endowed with ethnic diversity, there are some ingenious

efforts at ensuring effective minority representation, ranging from reserved

seats for the indigenous peoples in Taiwan and New Zealand; guaranteed seats

for national minorities in Croatia, Slovenia, and Romania; affirmative

gerrymandering for the Black and the Latinos in the U.S.; lower thresholds

for ethnic parties in Germany and Poland; nominating minority candidates in

safe constituencies, or ranking minorities higher on the party list; and

utilizing alternative votes to incorporate minorities’ perspectives (Figure

5).

* Presented at the

Conference on Electoral Reforms sponsored by the Democratic Pacific Union,

Foreign Service Institute, Taipei, 2005/12/4. |