|

原住民族的選舉制度──少數族群的代表性的國際觀點* |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

施正鋒 淡江大學公共行政學系暨公共政策研究所教授 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contrary

to those who find that group-differentiated politics only create division and

conflict, I argue that group differentiation offers resources to a communicative

democratic public that aims to do justice because differently positioned

people have different experience, history, and social knowledge derived from

that positioning. Iris Marion Young(2000:

136) ;…our

ability to put ourselves in other people’s shoes is

limited, however sincerely we try—and most of us are

not willing to try terribly hard. Will Kymlicka(1998:

111) 壹、前言 所謂選舉制度(electoral system),大體是指如何將選票換算成國會席次的方式;在不同的選舉制度之下,同一個政黨很可能會獲得不同的國會席次分配。就政治學上的意義來看,選舉制度左右著少數族群的代表性(minority

representation),也就是少數族群究竟在國會能獲得多少席次。對於少數族群來說,在國會是否能取得公平、或是充分的(fair, adequate)政治代表(political representation),意味著是否能夠實踐有效的(effective)政治參與(minority participation)(Phillips, 1995: 1)。 有效的少數族群政治參與至少有兩層重大的意義,一方面,起碼的描述性代表(descriptive、mirror、microcosmic representation)具有溝通上的功能,也就是讓少數族群的成員可以聽到自己人在國會發聲,進而在象徵上可以提高國家體制的正當性;另一方面,描述性代表如果能帶來實質的代表(substantive

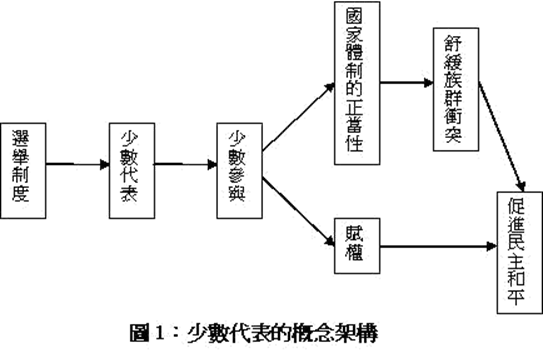

representation),也就是讓少數族群覺得自己的政治參與真的是有用的(efficacy),如此一來,投票選舉就具有賦權(empowerment)的作用(Banducci, 2004: Mansbridge, 2000)。在這樣的政治脈絡之下,如何設計出一套能讓少數族群在國會呈現(presence)的選舉制度,就消極面而言,至少可以舒緩內部原本的族群齟齬,特別是在多數族群願意分享權力(power-sharing)的情況下,就積極面而言,可以促進國家的民主、社會的和平(圖1)。

在威權統治時期,由於中國國民黨政府不允許國會改選,台灣的老百姓只能透過所謂增額補選方式來做有限的政治參與。在1973-93年之間,原住民族所分配到的的「第一屆立委」席次,逐漸由一名(1973-81)、二名(1981-90)、增加到四名(1990-93)。一直要到1991年第一次修憲的增修條文,原住民族在立法院的席次才正式訂為六名(1993-99,第二、三屆);在1997年的第四次修憲的增修條文,為了配合凍省/廢省,立法院的席次由164席增為225席,原住民族的席次跟著調整為八名(1999-2007,第四、五、六屆);在2005年的第七次修憲的增修條文,又因為國會減半為113席,未來原住民族立委的席次將只剩六名(2007-,第七屆起)。 在這裡,我們將由政治哲學對於少數族群代表、以及國際法對於少數族群的參與權著手,思考在設計國會議員的選舉制度之際,為何要設置原住民族的特別選區。我們在介紹了選舉制度、以及少數族群的代表如何呈現以後,會把考察的重點放在紐西蘭的毛利人國會議員選舉制度的發展。 貳、政治則學上的少數族群代表、以及國際法上的少數族群參與權 雖然公平的政治代表不能保證公平的政治參與、或是政治上的平等(political equality),不過,對於少數族群來說,如果能正式取得特別代表(special

representation)的保障,卻是獲得政治平等的必要條件(Williams, 1998: 6)。根據政治哲學家Iris Marion Young(2000)的看法,相對於直接民主(direct democracy),代議式民主(representative democracy)在本質上必須透過選民所產生的代表來中介民主政治的運作,也就是在政策的討論、制定、以及檢討的過程中,其利益、意見/理念、以及觀點/經驗能獲得能充分反映(頁124-25、133-41)。Young(2000: 18-21)以為,傳統的民主政治往往只重視機械性的選民偏好加總(aggregating

preferences),政黨及候選人因而只求汲汲於政治市場的激烈選票競爭,而那些在社會、經濟、或是文化上長期被排除在決策之外的社會團體(包括少數族群、或是原住民族),頂多只被允許有發言的機會,聊被一格,卻終究還是不得不屈從於多數選民的選擇;相對地,她認為在溝通式/審議式民主(communicative,

deliberative democracy)之下,所有的人都能獲得尊重而參與決策的討論、大家都能有公平的機會來有效表達自己的看法、彼此願意嘗試著以開放的態度來傾聽對方、眾人在相互負責中開創一個有意義的公共領域,如此一來,形式上的政治民主(political democracy)過程才能帶來實質上的社會公義(social justice),而少數族群才有可能擺脫結構性不平等與政治不平等相互強化的惡性循環(頁21-31)。 其實,除了促成民主、以及公義等終極的真正、內在(intrinsic)目標以外,充分的少數族群代表還有工具性的(instrumental)目的,也就是透過象徵性的權力分享,除了可以用來管理/化解族群之間的分歧,也可以提高國家體制的正當性。譬如Young(2000: 144-45)便列舉兩項支持少數族群特別代表的理由,也就是鼓勵族群間的互動交往、以及促進彼此之間的相互了解;而Will Kymlicka(1995:第七章)也認為,提供少數族群特別代表的理由,除了說是要參與相關政策的制定、以遏止政治體系的制度性歧視以外,另一方面是擔心少數族群在實踐自治權以後,恐怕會出現遺世獨立的情況,因此,如果能在國會提供保障名額,至少可以維持起碼的聯繫。 Kymlicka(1995: 26-33)將少數族群的權利(minority right)分為文化權、自治權、以及參與權/特別代表權。所謂的政治參與,就狹義來看,是指實質的權力分享、或是在國會的代表、甚至於選舉的參與;然而,就廣義而言,政治參與其實是包括諮商、決策、執行、監督、以及評估(Ghai, 2003: 12),因此,應該完整地涵蓋立法、行政、司法、以及體制外的諮詢制。在下面,我們將考察國際規約對於少數族群政治參與的規範,將可以看出國際社會對於國家的期許,絕對是超越消極的不作為、或是起碼的反歧視。 在聯合國的架構之下,『世界人權宣言』(1948)雖然沒有提及對於少數族群權利的保障,不過,卻特別提到「每個人擁有自由參與社群文化生活的權利」(27條1款): Everyone has

the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to

enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advancement and its benefits. 『國際公民暨政治權規約』(1966)、明文規定國家不可剝奪少數族群成員的文化權、宗教權、或是語言權,是少數族群權利在國際法上的最大突破(27條): In those States in which ethnic,

religious or linguistic minorities exist, persons belonging to such

minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members

of their group, to enjoy their own culture, to profess and practice their own

religion, or to use their own language. 聯合國大會在1992年通過『個人隸屬國籍、族群、宗教、或語言性少數族群權利宣言』,才真正全盤性試圖規範少數族群的權利。宣言除了要求國家必須保護其境內少數族群的國籍、族群、文化、宗教、以及文化認同(1條),並列舉少數族群成員有效參與文化、宗教、社會、經濟、以及公共生活(2條2款)、有效參與相關決策(2條3款)、以及保有自己的社團的權利(2條4款): 2. Persons belonging

to minorities have the right to participate effectively in cultural,

religious, social, economic and public life. 3. Persons belonging

to minorities have the right to participate effectively in decisions on the

national and, where appropriate, regional level concerning the minority to

which they belong or the regions in which they live, in a manner not

incompatible with national legislation. 4. Persons belonging to minorities

have the right to establish and maintain their own associations. 不過,有關於少數族群政治代表權的規範,還是可以在『國際公民暨政治權規約』(1966)找到,也就是每一個公民都有權利直接、或是透過自由選出的代表,來參與公共事務的進行,不應該因為族群差異而受到無理的限制(25條1款): Every citizen shall

have the right and the opportunity, without any of the distinctions mentioned

in article 2 and without unreasonable restrictions: 1. To take part in the conduct of

public affairs, directly or through freely chosen representatives;… 「歐洲安全暨合作會議」在1990年通過『哥本哈根宣言』,在其第四部份(30~40條),對於少數族群的權利作了詳細的規範。該宣言指出,少數族群的問題只能在民主的政治架構下獲得解決,此外,對於少數族群權利的尊重,是和平、公益、穩定、以及民主的必要條件(30條)。更重要的是,宣言規定要求會員國尊重少數族群有效參與公共事務的權利(35條): The participating

States will respect the right of persons belonging to national minorities to

effective participation in public affairs, including participation in the

affairs relating to the protection and promotion of the identity of such

minorities. The participating States note the

efforts undertaken to protect and create conditions for the promotion of the

ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious identity of certain national

minorities by establishing, as one of the possible means to achieve these

aims, appropriate local or autonomous administrations corresponding to the

specific historical and territorial circumstances of such minorities and in

accordance with the policies of the State concerned. 另外,OSCE在1999年通過的『蘭德有關少數族群有效參與政治生活建議書暨說明』,詳細規範少數族群的各種政治參與權。建議書首先指出幾項重要原則(第一部份):一個社會要獲致和平及民主,基本的條件是少數族群的有效政治參與(1條)。再來,建議書分別就參與決策(第二部份)、自治權(第三部份)、以及保障的機制(第四部份)作了詳細規範,譬如說:少數族群在國會、內閣、最高法院、及公家機構的保障名額(6條);選舉過程、組黨、選舉制度設計、及選區規劃(7-10條);地方政治參與(11條);設立聯繫少數族群與政府的諮詢機構(12-13條);設置地域式、或非地域式的自治機構(14-22條);以及過渡、及調解衝突機制(23-24條)。 「歐洲理事會」在1995年通過範圍廣泛的的『保障少數族群架構條約』,除了規定會員國必須採取必要措施,以確保少數族群與多數族群在經濟、社會、政治、以及文化生活上的平等(第4條),還特別要求會員國提供少數族群有利的條件,讓其成員能有效地參與文化/社會/經濟生活、以及公共事務,尤其是涉及他們的事務(15條): The Parties shall create the

conditions necessary for the effective participation of persons belonging to

national minorities in cultural, social and economic life and in public

affairs, in particular those affecting them. 雖然「歐洲聯盟」本身並沒有正式的少數族群政策,不過,歐盟在1991年公佈了『承認東歐及蘇聯新國家方針的宣言』,要求申請加入歐盟的國家,必須按照CSCE規定的架構來保障少數族群權利。歐盟的部長理事會 (Council of

Ministers) 進一步在1993年決議的『哥本哈根條款』(Copenhagen Criteria),要求想要加入歐盟的國家,必須尊重、及保護國內的少數族群,而執行委員會必須每年向部長理事會、以及歐洲議會提出各國進展的「定期報告」(regular reports): Membership requires that the candidate

country has achieved stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the

rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities, the

existence of a functioning market economy as well as the capacity to cope

with competitive pressure and market forces within the Union. Membership

presupposes the candidate's ability to take on the obligations of membership

including adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union. 另外,針對原住民族政治參與權利,聯合國「經濟暨社會理事會」所轄的周邊組織「國際勞工組織」,在1989年通過『原住暨部落民族條約』,要求會員國在採取與原住民族相關的立法、或是行政措施之際,必須徵詢其意見,特別是透過其具有代表性的制度(6條1款);此外,原住民族應該有權利決定自己發展的優先順系,並且能參與與其相關的發展計畫之制定、執行、以及評估(7條1款): In applying the provisions of this

Convention, Governments shall: (a) Consult the peoples concerned, through

appropriate procedures and in particular through their representative

institutions, whenever consideration is being given to legislative or

administrative measures which may affect them directly; The peoples concerned shall have the

right to decide their own priorities for the process of development as it

affects their lives, beliefs, institutions and spiritual well-being and the

lands they occupy or otherwise use, and to exercise control, to the extent

possible, over their own economic, social and cultural development. In

addition, they shall participate in the formulation, implementation and

evaluation of plans and programmes for national and

regional development which may affect them directly. 聯合國在1995年通過『原住民權利宣言草案』,主張原住民族有權透過以自己選擇的方式所產生的代表,來參與有關自己的事務的制定(19條);此外,原住民族有權以自己所決定的程序,參與與自己有相關的立法、及行政措施的制定(20條)。 Indigenous peoples have the right to

participate fully, if they so choose, at all levels of decision-making in

matters which may affect their rights, lives and destinies through

representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures

as well as to maintain and develop their own indigenous decision-making

institutions; Indigenous peoples have the right to

participate fully, if they so choose, through procedures determined by them,

in devising legislative or administrative measures that may affect them. 我們可以看到,國際規約裡頭有關於少數族群的政治參與,並不限於在國會的代表性,還包括在行政部門、或是司法部門的參與;甚至於,垂直的自治架構的安排,也可以視為一種參與權的實踐(Ghai, 2003; Frowein & Bank, 2000)。不過,有人或許會以行政效率、或是司法獨立為由,藉口專業能力的色盲而排除少數族群,只願意接受少數族群在國會的樣板式代表,這就是將政治參與作最狹隘的解釋,其實是對於現有政治制度可能鑲嵌、暗藏的(embedded)族群偏見視若無睹。 參、選舉制度與少數族群代表

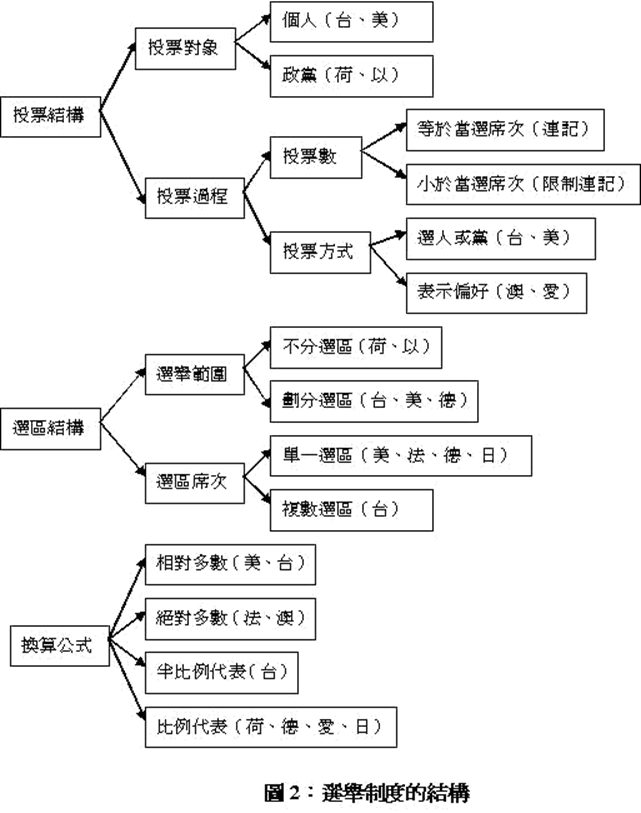

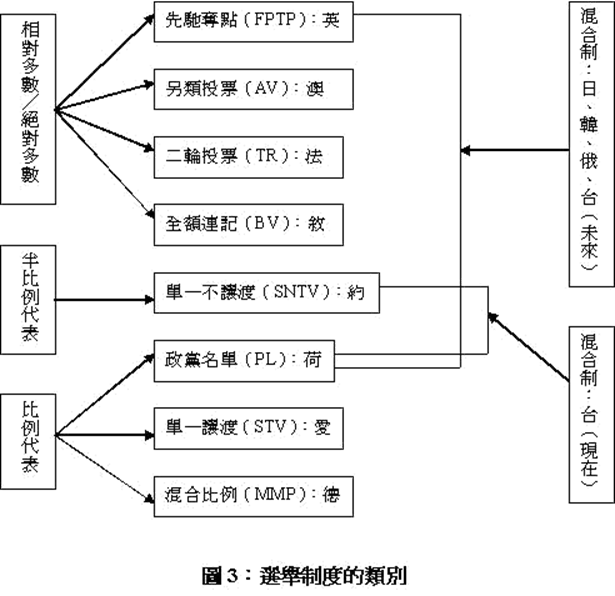

就國會議員選舉制度的結構面來看,我們可以解析為投票結構(包含投票對象、投票過程)、選區結構(包含選區範圍、選區大小)、以及換算公式(包含相對多數、絕對多數、比例代表制、半比例代表制)三個層面(圖2);如果我們根據換算公式來看,大致可以歸納為相對多數/絕對多數、比例地表制、半比例代表制、以及混合制(施正鋒,1999:229-35;Reynolds & Reilly, 1997: 4;

Reynolds, et al.: 2005: 28; Taagepera & Shugart, 1989: 9-37)(圖3)。

所謂「相對多數」(plurality),是指由選區之中得票最高的候選人當選;如果是在單一選區(single-member

district)的情況下,稱為「先馳奪點制」(first

past the post、簡寫為FPTP),譬如美國、英國、加拿大。如果是要求「絕對多數」(majority),是指當選人必須獲得選區的過半席次,一般而言,可以有兩種方式,第一種是法國、以及其前殖民地所採用的「二輪投票」(two-run、簡寫為TR),是指如果在第一輪沒有人贏得過半選票,必須進行第二輪的投票:二輪投票又分為「過半決賽」(majority run-off TR)、以及「多數決賽」(majority-plurality TR)兩種,前者是指如果必須進行決賽,只留第一輪得票最高的兩個候選人,以確保當選者的得票數一定會過半;後者是只在進行決賽之際,只允許在第一輪得票達到某種百分比的候選人進入決賽,因此,當選人物不一定會得票過半(Reynolds, et al.:

2005: 52-53)。 另一種取得絕對多數方式是澳洲採取所謂的「另類投票」(alternative vote、簡寫為AV),也就是選民投票之際必須根據自己對於候選人的偏好來排序(1、2、3等等),如果沒有人獲得過半的最佳偏好(也就是1)的支持,那麼,選務單位將把得到最低最佳偏好的候選人支持者的票重新檢視,將其次佳偏好的票分配給其候選人,一直到有人獲得過半選票為止。 另外,比較透別的是「全額連記」(block vote、簡寫為BV),是指在複數選區(multiple member district)的情況下,如果選區有多少席次,選民就可以選多少人,譬如巴勒斯坦、黎巴嫩、敘利亞、科威特、寮國、以及東加等國,而約旦、泰國、菲律賓、以及蒙古先前也採用這種選舉制度(Reynolds,

et al.: 2005: 44-47)。 另外,新加坡、查德、喀麥隆、以及吉布地採用「政黨連記」(party block vote、簡寫為PBV),是指在復數選區之下,每個政黨必須提出一個政黨名單,而選民只有一票,由得票最高的政黨贏者全拿(Reynolds, et al.:

2005: 47);其實,由於選民的選票有加乘的效果,我們可以視之為「超級先馳奪點制」。 至於「半比例代表制」(semi-proportionality

representation),是指選舉制度的比例性(proportionality)介於相對多數/絕對多數、以及「比例代表制」(proportionality

representation)之間;台灣目前的區域立委、約旦、以及阿富汗的國會議員選舉屬之,也就是不管是在單一選區、還是複數選區之下,選民只有一張選票,由得票最高的候選人當選,稱為「單一不讓渡制」(single

non-transferable vote、簡寫為SNTV)(Reynolds, et al.:

2005: 113)。 顧名思義,比例代表制是指根據政黨所得票數的比例來分配國會的席次,總共有三種常用的分配方式。最常見的是「政黨名單」(party list、簡寫為PL),也就是在複數選區之下(或是全國部分選區),每個政黨都有一個提名的名單,看選民支持的程度來決定名單上有多少人可以當選,譬如荷蘭、瑞典、以色列、南非、以及台灣的不分區立委(Reynolds,

et al.: 2005: 71-91)。再來是愛爾蘭、以及馬爾他所採取的「單一讓渡制」(single

transferable vote、簡寫為STV),是指在複數選區之下,選民依據對於候選人的偏好來排序,只要有人得票超過某個數額(quota)就可當選,否則,就以淘汰的方式,計算其支持者的次佳偏好來計票(Reynolds,

et al.: 2005: 113-17; Zvulun, 2004)。 最特別的比例代表制是「混合比例制」(mixed member

proportionality、簡寫為MMP),表面上看來是一種由比例代表制與區域選舉(一般是單一選區)混合的選舉制度,事實上,卻是一種實質(effective)的比例代表制。在這樣的選制之下,選民有兩張選票,一張投給選區的候選人(electorate vote)、一票投給政黨(party vote、或是list vote);最重要的是,政黨所獲得的總席次是由政黨票的百分比來計算,因此,在扣掉各黨的選區席次以後(有可能沒有半席),其他的就是可以補足的(added up、compensation for)政黨名單席次,因而又稱為「補足式選制」(additional member

system、簡寫為AMS)。最早採取混合比例制的國家為德國,而紐西蘭在1993年跟進,其他還有玻利維亞、墨西哥、委內瑞拉、以及匈牙利(Reynolds, et al.: 2005: 91-103)。 最後是狹義的「混合制」(mixed

system),也就是選民有兩張票,一張投給人、一張投給黨,兩者加起來就是政黨所獲得的席次總數,因此又稱為「並立制」(parallel system)。在混合制之下,每個國家的區域席次以及政黨比例之間的比例未必相同,譬如俄羅斯是5:5、日本是6:4、台灣與韓國皆約略為8:2(Reynolds, et al.: 2005: 104-12)。目前,台灣與其他採取混合制的國家最大的不同,是區域採大多為複數選區相對多數,也就是半比例代表制,而非單一選區相對多數(先馳奪點)、或是絕對多數;此外,台灣的選民目前只能選區域立委,再透過當選人的政黨屬性來計算政黨的得票率,也就是小雞帶母雞的方式。今年(2005)修憲以後,未來的立委選舉將與大多數採行混合/並立制的國家相仿,也就是說,在區域立委方面,除了原住民的六席立委產生方式未定,非原住民立委73席將以先馳奪點的方式產生。 就政治制度設計的觀點來看,選舉制度的重要性在於它有宏觀(macro)、以及微觀的(macro)政治效應:前者包括政黨席次的比例性、政黨數目/政黨體系、以及少數族群的代表;後者包括選民、候選人、以及政黨的行為。首先,就比例性而言,顧名思義,比例代表制的原意就是要追求政黨所分配的席次儘量與其得票比例相當,而前馳奪點制的出發點除了是強調代議士與選區的密切關係,最大的特色是往往會擴張兩大黨的席次,大體不利於第三黨、或是小黨的發展。此外,由於比例代表制可以確保小黨獲得相當比例的國會席,因此有利於多黨制的發展,相對之下,先馳奪點制有利於兩黨制的發展。再來,就比較政治學上的經驗來看,學者大體同意比例代表制比較有利於少數族群在國會獲得起碼的代表,而前馳奪點制大致是比較不利於少數族群產生國會議員;事實上,歐洲大陸國家的選舉制度採取比例代表制,多少也是考慮到如何確保少數族群的代表。 不過,對於少數族群來說,如果其地域性的分佈如果相當集中,尤其是人口比例實質過半的情況下,不管是比例代表制、還是前馳奪點制,都還可以獲得起碼的國會代表。譬如在西班牙的民主化過程中,巴斯克人並未特別堅持採行比例代表制;相對地,在近年來的立委選制改革呼聲當中,朝野的共識是單一選區兩票制,也就是區域立委採先馳奪點制、又由選民直接投票給政黨來決定政黨比例,然而,小黨就比較偏好混合比例制,也就是德國式的聯立制,主要是擔心其支持者四散全國,恐怕在混合制之下,也就是在大黨喜歡的日本式的並立制之下,先馳奪點制帶來的衝擊較大。 根據「新制度論」(Neo-Institutionalism)的說法,制度可以提供政治人物行動的誘因/機會、也可以構成障礙/限制,如此一來,制度可以塑造行為者的偏好、以及定義其利益(Thelen & Steinmo, 1992; Koelbe, 1995:

239; Goodin, 1996);在這樣的架構下,妥適的選舉制度可以扮演正面(affirmative)需求面的角色,以彌補少數族群因為負面的結構性歧視所造成的候選人供給不足(Bird:

2004)。近年來,研究民主化、或是衝突管理(conflict management)的學者,開始由制度設計著手,思考如何在多元族群的國家裡頭,透過選舉制度的擘畫,促成少數族群在國會有公平的代表,以確保其有效的政治參與、達到彼此的權力分享(Bastian & Luckham, 2003; Bird, 2004; Horowitz, 1991; Htun, 2004; Illinois Assembly on Political Representation

and Alternative Electoral Systems, 2001; Lijphart,

1986; OSCE/ODIHR, 2001; Reilly, 2001; Reilly & Reynolds, 1998, 1999; Schneckener & Wolff, 2004; Sisk, 1996; Sisk &

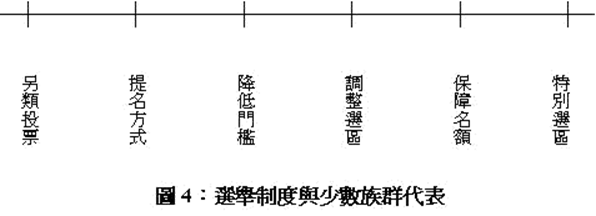

Reynolds, 1998; Venice Commission , 2000)。我們可以將促進少數族群的選舉機制,依光譜歸納為特別選區、保障名額、調整選區、降低門檻、提名方式、以及另類投票六大類(圖4)。

(一)特別選區 特別選區(reserved seat、或是dedicated seat)是指針對少數族群特別劃出的選區,限定具有少數族群身分的人當候選人、並且由少數族群投票選出,譬如約旦、尼日、巴基斯坦、巴勒斯坦、西薩摩亞;在原住民族方面,印度的原住民族(scheduled tribes)、以及特別種姓階級(scheduled castes)、哥倫比亞的原住民族(black communities)、紐西蘭的毛利人、以及台灣的原住民族,在國會議員選舉有自己的特別選區(Reynolds,

2005; Reynolds, et al.: 2005: 122)。 如果將這種屬人式的少數族群選區推到極致,就是根據選民的族群身分有不同的選舉名冊(roll),乾脆由各族群推舉自己的代表(separate

representation、communal

representation),譬如斐濟、黎巴嫩、以及過去的塞浦路斯、巴基斯坦、以及津巴布威(Reynolds,

et al.: 2005: 122-23)。就制度發展的歷史脈絡來看,這是受到奧圖曼土耳其統治的millet制度(族群分治)、或是英國殖民傳統的影響。 (二)保障名額 保障名額(guaranteed seats)與特別選區相仿,因此,學者有時候會將兩個混在一起討論;兩者的差別在於保障名額只規定在當選的名單裡頭,少數族群一定要達到某種百分比、或是額度(quota),而特別選區是讓少數族群直接推選自己的國會議員。保障名額通常用於婦女代表的產生,至於少數族群方面,有克羅埃西亞、斯洛文尼亞、以及羅馬尼亞採取保障名額。 (三)調整選區 調整選區(affirmative

gerrymandering)是指在單一選區之下,在進行選區規劃/重劃(redistricting、或是reapportionment)之際,刻意將少數族群的選民劃在同一個選區(packing),設法讓他們可以選出自己人當議員,以免其選票因為無法集中而浪費掉(wasted),藉以改善少數族群在國會代表不足(under representation)的情況,譬如非洲裔美國人(African American)、以及西班牙裔美國人(Latino)的選區規劃。 (四)降低門檻 雖然在比例代表制之下,少數族群要進入國會的機率比在先馳奪點制之下來得高,卻未必真的能選的上,特別是人口不多的情況下,因此,如果能降低政黨分配國會席次的得票門檻(threshold)、或是取消族群政黨的門檻,以減輕少數族群進入國會的形式障礙,就可能間接達成儘量讓少數族群席次達到最高的目的,譬如德國、以及波蘭。 (五)提名方式 在採取先馳奪點制之下,如果政黨能提名、或是徵召少數族群,尤其是在鐵票區,當然可以保證少數族群的當選。在採取政黨名單的比例代表制之下,如果政黨能將少數族群候選人放在安全名單,更不用擔心少數族群的分佈是否四散、或是人數過少。這兩種不觸及選舉制度變動的做法,往往有示範效果,譬如在台灣的不分區立委選舉,民進黨從第三屆立委開始,開始將原住民族置於不分區立委的定安全名單(巴燕.達魯),親民黨(蔡中涵)與國民黨(陳建年)也在第五屆開始仿效。 (六)另類投票 另類投票的最大特色是透過選票的匯集(vote-pooling)、以及偏好的表達,鼓勵族群之間的合作;具體而言,就是沒有候選人在單一選區有把握獲得過半席次之際,必須想辦法爭取少數族群的次佳偏好,特別是在政策面的讓步。也就是說,即使少數族群本身未必能在國會有席次,卻依然可以透過友好族群的代表來發聲。到目前為止,只有巴布亞新幾內亞在獨立之前所舉辦的三次選舉(1964、1968、1972)、以及斐濟用過另類投票,Horowitz(1991)當年也大力鼓吹民主化的南非採取另類投票(Reynolds, 1999; Reilly &

Reynolds, 1999: 32-36)。 伍、紐西蘭毛利人代表 紐西蘭在1867年通過『毛利代表法』(Maori Representation

Act),保留四個以先馳奪點制選出的國會議員選區給毛利人,稱為「毛利席次」(Maori Seat)。從1996年大選以來,毛利人的國會保障名額席次逐漸由4席增為7席(1996/5、1999/6、2002/7);不過,如果根據人口比例,毛利人的席次應該是不只這些。還好,紐西蘭在該年大選起,開始採取德國式的混合比例代表制,除了保留毛利席次以外,政黨也提名具有毛利血統的人參加非毛利選區的選舉,以拉高政黨的整體得票率,讓毛利國會議員的人數倍增(Barker, et al., 2001: 307-8;

Catt, 1997: 200-201; Sullivan & Vowles, 1998)。 相對之下,台灣的立委選制雖然已經有所調整,也就是將區域立委由單一不讓渡制改為先馳奪點制,至於原住民族的六席立委如何產生,目前懸而未決。雖然台灣的並立式選制與紐西蘭的聯立式混合比例制不盡然相同,不過,兩國都採用特別選區的方式來選舉原住民族,因此,紐西蘭將近十年的實證經驗,對於台灣原住民族的政治代表、以及政治參與,應該可以有他山之石的效果。我們在下面,將先回顧毛利席次的來龍去脈,再來檢視皇家選舉制度委員會的觀點,最後考察實際運作的情形。 跟大部分受到安格魯.薩克森文化影響的國家一樣,紐西蘭的國會議員選舉採取先馳奪點制,也因此,長久以來,政黨政治是由工黨(Labour Party)、以及國家黨(National Party)所支配。在1980年代,由於當政者因為受庇於兩黨制所產生的「選舉獨裁」(elective

dictatorship)而疏於反映民意,選民對於朝野行禮如儀的政黨輪流執政漸感不耐,傳統的政黨認同開始鬆動,因此埋下了選制改革的契機;工黨政府所特別任命的「皇家選舉制度委員會」在1986年提出一份《邁向更好的民主》(Toward a Better

Democracy)的報告書,建議政府改採德國式的混合比例制,並且先後後得1992年的諮詢性公投、以及1993年的正式公投確認,隨即於1996年的大選中開始改弦更張(Boston, et al.,

1996; Denemark, 2001: 88-92; Palmer & Palmer,

1997; Rudd & Taichi, 1994)。 毛利席次是在1867年創設的,當時的背景是因為按照規定,具有投票權的選民(男人)必須符合起碼的私有財產條件,而毛利人自來只有集體擁有財產的傳統,幾乎所有的毛利男人勢必實質失去投票的資格,因此,才特別為他們量身製衣通過『毛利代表法』,給予四席特別的單一選區,讓21歲以上的男性毛利人擁有投票權,開始紐西蘭百年來國會的雙元代表(dual representation)現象。不過,毛利席次的設計並非特例,因為Otago、以及Westland的淘金者也先後(1862、1867)因為沒有恆產而獲得特別代表(RCES, 1986: 83);此外,原本毛利席次的設計是暫時的安排,也就是預期在五年以後,當毛利人所有的集體擁有土地重新分配給個人以後,就可以加以廢除;不過,事與願違,政府只好在1872年再延期五年,仍舊無法達成目標,終於在1876年無限延期;雖然一般選民的財產資格終究在1896年被廢除,不過,毛利人還是依然被要求分開投票(Iorns, 2003)。其實,白人、以及毛利人之所以對於毛利席次的常態化有所共識,其實是有不同的考量:對於白人來說,當時的毛利人口為五萬人,而一般選區的平均選民數為3,500人(25萬人、72席),因此,如果讓毛利人跟墾殖者混在一起投票,很可能會稀釋白人選票的權重;相對地,毛利人也認為特別選區才可以保障自己,因此,只要求依照人口比例,將席次增為14席(Iorns, 2003)。 一開頭,毛利人將自己的國會議員視為派出的大使,而非參與國會運作的代表;事實上,由於毛利人在國會的呈現只有象徵意義,他們的聲音不被重視,連攸關族人實質利益的法案也不能真正有所影響,只能用來救贖白人的良心;不過,隨著諳英語的毛利菁英加入國會議員,他們的影響力日增,特別是從1935年起,工黨開始提名黨員參選毛利席次,毛利人才涉及政黨政治的運作(Iorns, 2003)。 皇家選舉制度委員會(RCES,

1986: 85-87)列舉了毛利席次的象徵意義、以及實質利益,包括自治/自決的實踐、確保『外坦及條約』(Treaty of Waitangi)所承諾的權利、以及保存文化及認同,同時也提出五項評判毛利代表的原則(頁88): 2.

毛利人的選票若要有效,必須由所有的政黨來競爭; 3.

所有的國會議員必須在某種程度上對毛利選民負責; 4.

所有的毛利國會議員必須對毛利選民作民主負責; 5.

政黨的提名過程必須允許毛利人的意見能影響決策。 根據這些原則,皇家選舉制度委員會(RCES, 1986: 89-98)也臚列了正反兩方對於毛利席次所提出的看法。大體而言,他們認為毛利席次滿足上述的基本要求,不過,也同時提出下列的意見: 1.

在民主政治之下,多數決應該是依據議題而有所浮動,不應依族群人數的多寡而凍結,然而,隨著分別代表而來的是政治分隔,因此,不管是毛利、還是非毛利議員,他們終究都只專注對於特定的社區負責;也就是說,如果毛利議員只想對族人負責,佔絕大多數的非毛利人議員也會做如此想,如此一來,毛利議員在相關毛利的政策制定過程中,勢必造成仰人鼻息的情況。 2.

先馳奪點的選舉方式造成兩黨制,進而強化原本毛利代表的倚賴,特別是毛利人一向支持工黨,讓政黨覺得毛利席次無足輕重,無形中削弱毛利議員透過政黨來保障毛利福祉;又因為毛利議員無法獲得政黨的奧援,他們的代表其實是無效的。委員會認為,釜底抽薪之計,是想辦法調整選制,讓毛利人能獲得公平的政治權力,而非賦予他們有少數否決的權力。 3.

雖然毛利席次也是採用單一選區,不過,毛利選區的範圍往往比一般選區還來得大,因此,就選區服務而言,毛利議員的工作比非毛利議員來得沉重,因此,如果能增加毛利席次,雖然未必能提高毛利人在國會的整體力量,不過,至少可以減輕毛利議員服務選民的負擔。另外,選區的範圍過大,多少也造成政黨不願意在毛利社區發展草根組織,如此一來,不僅是地方缺乏催票的機制,黨中央也也缺乏發展毛利政策的聲音,連帶地,毛利議員在國會裡頭也會被認為沒有真正的社會支持。 4.

不管毛利人口的成長,毛利席次自來就被定為四席,相對地,一般席次卻一再增加,顯然不公。雖然工黨政府在1975年透過立法,同意根據多少毛利人選擇將自己放在毛利選舉名冊,來決定毛利席次的多寡,不過,這項規定卻在次年被國家黨政府廢止(Jackson & McRobie, 1998: 213)。 總之,皇家選舉制度委員會的基本立場是反對毛利席次,不過,卻又擔心一旦廢除毛利特別選區,很可能毛利人就選不上國會議員,或是選出來的人沒有代表性、或是只是聽命於政黨的人,因此:(一)建議廢除毛利席次,也就是全盤取消毛利選區、毛利選舉名冊、以及毛利選擇;(二)將先馳奪點制改為混合比例制,並且將政黨比例的得票門檻定為4%,以利毛利政黨進入國會;(三)在規劃單一選區之時,應該考慮毛利部落的範圍(RCES,

1986: 98-101)。委員會認為,在這樣的選制之下,毛利選票比較不被綁死,政黨就會比較會重視毛利選票,因此,除了在有選勝機會的一般選區提名毛利人,也會把毛利人放在政黨比例名單的前面(頁102)。 紐西蘭「國會選舉制度改革特別委員會」在審查皇家選舉制度委員會的報告之後,雖然決定採用混合比例制,不過,卻維持毛利席次的設置,並在1996年的大選開始實施(Iorns, 2003)。根據1993年的『選舉法』(Electoral Law),毛利席次將依據毛利人名冊上的人數來彈性調整;目前,毛利席次已增為7席(表1)。 表1:毛利席次與毛利議員

紐西蘭眾議院的「混合比例制審議委員會」提出一份報告(MMPRC,

2001),綜合各方的意見,毛利人強烈表達毛利席次在文化、以及憲政上的意義,而大多數的政黨也沒有廢除毛利席次的意思;甚至於有人指出,維持原有的毛利選擇(投一般選區、還是毛利選區),其實就是一種毛利人的公投,如果有一天大多數的毛利人選擇一般選區,毛利選區就會自動消失(MMPRC,

2001: 20-21)。整體而言,紐西蘭在採取混合比例制以後,毛利人在國會的席次大增,而且與其人口百分必相當;事實上,若非有政黨名單,國家黨、或是消費者暨納稅人黨恐怕不會有毛利議員當選。 陸、結語 回顧第二次台灣人民制憲會議通過的『台灣共和國憲法草案』(1994)、陳水扁總統大選前與原住民族運動者簽定的『原住民族與台灣政府新的夥伴關係』(1999)、以及選後的『原住民族與台灣政府新的夥伴關係再肯認協定』(2002),都主張「原住民族國會議員回歸民族代表」,也就是原住民族的每個族在國會應至少有一席,因為不管人口多寡,每個族都是獨一無二的,應該在國會有發言權。在這次修憲的過程中,朝野政黨步調一致,順勢將原住民族立委的席次由八名調為六名,對於究竟多少才是合理的數目,並未真正有深入的討論,甚至於有六席仍然稍嫌過多的聲音。 在粥少僧多的情況下,如果我們在未來的台灣新憲中作沒有辦法將國會的席次提高、或是有類似許世楷所主張的國會民族院的安排,那麼,面對原住民族內部多元所帶來的實踐可行性挑戰,我們或許可以重新思考少數族群代表的真諦,也就是說,究竟只要滿足泛原住民族在整體社會的代表就好、還是各原住民族至少要在國家體制裡頭有起碼的某種代表性?如果是後者,目前行政院原住民族委員會所採取的各族委員,是一種妥協式的安排,比較像是澳洲的「原住民暨托雷斯海峽群島人委員會」的做法。 國際規約 Universal

Declaration of Human Rights (1948)『世界人權宣言』(http://www.un.org/

Overview/rights.html) International

Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966)『國際公民暨政治權規約』(http://www.hrweb.org/legal/cpr.html) ILO Convention 169: Convention

Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (1989)『國際勞工組織原住暨部落民族條約』(http://www.unhchr.ch/

html/menu3/b/62.htm) Document of the

Copenhagen Meeting of the Conference of the Human Dimension of the CSCE (1990)『哥本哈根宣言』(http://www.osce.org/docs/english/1990-1999/

hd/cope90e.htm) Declaration on the

Guidelines on the Recognition of New States in East Europe and the Soviet

Union

(1991)『承認東歐及蘇聯新國家方針的宣言』(http://www.univie.ac.at/

intlaw/pdf/D85n.pdf) Declaration on the

Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious or Linguistic

Minorities (1992)『個人隸屬民族、族群、宗教、或語言性少數族群權利宣言』(http://www.anaserve.com/~mambi/Derechos/2Minorit.html) Copenhagen Criteria (1993) 『哥本哈根條件』(http://www.europarl.eu.int/enlargement/ec/

cop_en.htm) Framework

Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (1995)『保障少數族群架構條約』(http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/euro/ets157.html) United

Nations Draft Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (1995)『聯合國原住民族權利宣言草案』(http://www.usask.ca/nativelaw/ddir.htm) Lund Recommendations on the Effective Participation of National

Minorities in Public Life and Explanatory Note (1999) 『蘭德有關少數族群有效參與政治生活建議書暨說明』(http://www.osce.org/hcnm/documents/recommendations/

lund/index.php3) 參考文獻 施正鋒。2005。《台灣原住民族政治與政策》。台中:新新台灣文化教育基金會/台北:翰蘆圖書出版公司。 施正鋒。2004a。《台灣客家族群政治與政策》。台中:新新台灣文化教育基金會/台北:翰蘆圖書出版公司。 施正鋒。2004b。〈總統大選以來的民進黨與泛綠陣營〉《台灣民主季刊》1卷,3期,頁213-30。 施正鋒。1999。《台灣政治建構》。台北:前衛出版社。 施正鋒。1995。《台灣憲政主義》。台北:前衛出版社。 余明德。2005。〈原住民的參政史〉(未發表論文)。 Archer,

Keith. 2003. “Representing Aboriginal Interests: Experiences of

New Zealand and Australia.” Electoral Insights, Vol. 5, No. 3,

pp. 39-45. Banducci, Susan A., Todd Donovan, and

Jeffrey A. Karp. 2004. “Minority Representation, Empowerment, and

Participation.” Journal of Politics, Vol. 66, No. 2, pp. 534-56. Barker,

Fiona, Jonathan Boston, Stephen Levine, Elizabeth McLeay, and Nigel S.

Roberts. 2001. “An Initial Assessment of the Consequences of MMP

in New Zealand,” in Mathew Sobert Shugart, and Martin P. Wattnberg,

eds. Mixed-Member Electoral Systems: The Best of Both World?

pp. 297-322. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bastian,

Sunil, and Robin Luckham, eds. 2003. Can

Democracy Be Designed? The Politics of Institutional Choice in Conflict-torn

Societies. London: Zed Books. Bird,

Karen. 2004. “The Political Representation of Women and Ethnic

Minorities in Established democracies: A Framework for Comparative

Research.” AMID Working Paper Series

(http://ipsa-rc19.anu.au/papers/bird.htm). Blair, George S.

1960. Cumulative Voting: An Effective Electoral Device in Illinois

Politics. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. Blais, Andre, Louis Massicotte, 1996. "Electoral Systems," in

Lawrence LeDuc, Richard G. Niemi,

and Pippa Norris, eds. Comparing Democracies:

Elections and in Voting in Global Perspective, pp. 49-81. Thousand

Oaks, Calif.: Sage. Bogdanor, Vernon. 1984. What

Is Proportional Representation? A Guide to the Issues. Oxford:

Martin Robertson. Boston,

Jonathan, Stephen Levine, Elizabeth McLeay, and Nigel S. Roberts.

1996. New Zealand Under MMP: A New Politics? Auckland:

Auckland University Press. Bowler,

Shaun, Todd Donovan, and David Brockington.

2003. Electoral Reform and Minority Representation: Local

Experiments with Alternative Elections. Columbus: Ohio State

University Press. Catt,

Helena. 1997. “Woman, Maori and Minorities: Microrepresentation

and MMP,” in Jonathan Boston, Stephen Levine,

Elizabeth McLeavy, and Nigel S. Roberts, eds. From

Campaign to Coalition: New Zealand’s First General

Election Under Proportional Representation, pp. 199-205. Palmerston North, New

Zealand: Dunmore Press. Chapman,

Robert. 1986. “Voting in the Maori Political Sub-System,

1935-1984,” Printed as Annex to K. Sorrenson’s “A History of Maori Representation in Parliament,”

Printed as Appendix B to Royal Commission of the Electoral System’s Toward a Better Democracy. Wellington, New

Zealand: Government Printer. CIA.

2005. “New Zealand,” in The World Factbook (http://www.cia.gov/publications/ factbook/print/nz.html). Denemark, David. 2001.

“Choosing MMP in New Zealand: Explaining the 1993 Electoral Reform,” in Mathew Sobert Shugart, and Martin P. Wattnberg,

eds. Mixed-Member Electoral Systems: The Best of Both World?

pp. 70-95. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Dummett, Michael. 1997. Principles

of Electoral Reform. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Farrell,

David M. 1997. Comparing Electoral Systems.

Hertfordshire: Prentice Hall/Harvest Wheatsheaf. Fleras, Augie.

1985. “From Social Control towards Political Self-Determination: Maori

Seats and the Politics of Separate Maori Representation in New

Zealand.” Canadian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 18, No. 3,

pp. 551-76. Fleras, Augie, and Jean Leonard Elliott. 1992. The

Nations within: Aboriginal-State Relations in Canada, the United States, and

New Zealand. Toronto: Oxford University Press. Frowein, J. A., and Ronald Bank.

2000. “The Participation of Minorities in Decision-Making

Processes.” Expert Study Submitted on Request of the DH-MIN of the

Council of Europe (http://www.humanrights.coe.int/Minorities/Eng/Inter

Governmental/Publications/dhmin20001.htm). Gay,

Oonagh. 1998. Voting Systems: The

Jenkins Report. London: House of Commons Library. Ghai, Yash.

2003. Public Participation and Minorities. London:

Minority Rights Group International. Goodin, Robert E. 2003.

“Representing Diversity” (pdf). Goodin, Robert E. 1996.

“Institutions and Their Design,” in Robert E. Goodin,

ed. The Theory of Institutional Design, pp. 1-53.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Grofman, Bernard, ed.

1998. Race and Redistricting in the 1990s. New York: Agathon Press. Grofman, Bernard, ed.

1990. Political Gerrymandering and the Courts. New York: Agathon Press. Grofman, Bernard, and Chandler

Davidson, eds. 1992. Controversies in Minority Voting: The

Voting Rights Act in Perspective. Washington, D.C.: Brookings

Institution. Grofman, Berbnard,

Lisa Handley, and Richard G. Niemi.

1992. Minority Representation and the Quest for Voting Equality.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Grofman, Bernard, and Arend Lijphart, eds.

1986. Electoral Laws and Their Political Consequences. New

York: Agathon Press. Grofman, Bernard, and Arend Lijphart, Robert B.

McKay, and Howard A. Scarrow, eds.

1982. Representation and Redistricting Issues. Lexington,

Mass.: D.C. Heath & Co. Guinier, Lani.

1994. The Tyranny of the Majority: Fundamental Fairness in

Representative Democracy. New York: Martin Kessler Books. Horowitz,

Donald L. 1991. A Democratic South Africa: Constitutional

Engineering in a Divided Society. Berkeley: University of

California Press. Horowitz,

Donald L. 1985. Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley:

University of California Press. Htun, Mala. 2004. “Is

Gender Like Ethnicity? The Political Representation of Identity

Groups.” Perspectives on Politics, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 439-58. Hunter,

Anna. 2003. “Exploring the Issues of Aboriginal Representation in

Federal Elections.” Electoral Insights, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp.

27-33. Illinois

Assembly on Political Representation and Alternative Electoral Systems.

2001. Final Report and Background Papers. Urbana, Ill.:

Institute of Government and Public Affairs, University of Illinois. Iorns, Catherine. 2003.

“Dedicated Parliamentary Seats for Indigenous Peoples: Political

Representation as an Element of Indigenous Self-Determination.” E

Law, Vol. 10, No. 4 (http://www.murdoch.edu.au/elaw/issues/v10n4/iorns104_text.html). Jackson,

Keith, and Alan McRobie. 1998. New

Zealand Adopts Proportional Representation. Aldershot,

England: Ashgate. Jesse,

Eckard. 1990. Elections: The Federal

Republic of Germany in Comparison. New York: Berg. Knight,

Trevor. 2001. “Electoral Justice for Aboriginal Peoples in

Canada.” McGill Law Journal, Vol. 46, pp. 1063-116. Koelble, Thomas A. 1995.

“The New Institutionalism in Political Science and Sociology,” Comparative

Politics, Vol. 27, No. 2, pp. 231-43. Kymlicka, Will.

1998. Finding Our Way: Rethinking Ethnocultural

Relations in Canada. Don Hills, Ont.: Oxford University Press. Kymlicka, Will. 1995. Multicultural

Citizenship: A Liberal Theory of Minority Rights. Oxford: Clarendon

Press. Lakeman, Enid. 1982. Power

to Elect: The Case for Proportional Representation. London: William

Heinemann. Lijphart, Arend.

1994. Electoral Systems and Party Systems: A Study of Twenty-Seven

Democracies 1945-1990. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lijphart, Arend.

1986. “Proportionality by Non-PR Methods: Ethnic Representation in

Belgium, Cyprus, Lebanon, New Zealand, West Germany, and Zimbabwe,” in Bernard Grofman, and Arend Lijphart, eds. Electoral

Laws and Their Political Consequences, pp. 113-23. New York: Agathon Press. Lijphart, Arend,

and Bernard Grofman, eds. 1984. Choosing

an Electoral System: Issues and Alternatives. New York: Praeger. McKay,

Robert B. 1970 (1965). Reapportionment: The Law and Politics

of Equal Representation. New York: Clarion Book. Mansbridge, Jane. 2000. “What

Does a Representative Do? Descriptive Representation in Comparative Setting

of Distrust, Uncrystallized Interests, and

Historically Denigrated Status,” in Will Kymlicka, and Wayne Norman, eds. Citizenship in

Diverse Societies, pp. 99-123. Oxford: Oxford University Press. MMP

Review Committee. 2001. Inquiry into the Review of MMP.

Wellington, New Zealand: House of Representatives. Návrat,

Petr. 2003. Comparative Study of Electoral Systems and Their

Features. Hyderabad, India: Foundation for Democratic Reforms. Nurmi, Hannu.

1987. Comparing Voting Systems. Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Co. OSCE,

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights. 2001. Guidelines

to Assist National Minority Participation in the Electoral Process.

Warsaw: Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, OSCE (pdf). Palmer,

Geoffrey, and Matthew Lamer. 1997. Bridled Power: New Zealand

Government under MMP. Auckland: Oxford University Press. Phillips,

Anne. 1995. The Politics of Presence: The Political

Representation of Gender, Ethnicity, and Race. Oxford: Clarendon

Press. Pitkin,

Hanna Fenichel. 1967. The Concept of

Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press. Rae,

Douglas W. 1967. The Political Consequences of Electoral Laws.

New Have, Conn.: Yale University Press. Reeve,

Andrew, and Alan Ware. 1992. Electoral Systems: A Comparative

and Theoretical Introduction. London: Routledge. Reeves,

Simon. 1996. To Honor the Treaty: The Argument for Equal Seats.

Auckland: Earth Restoration. Reilly,

Ben, and Andrew Reynolds. 1999. Electoral Systems and Conflict

in Divided Societies. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. Reilly,

Ben, and Andrew Reynolds. 1998. “Electoral Systems for Divided

Societies,” in Peter Harris, and Ben Reilly, eds. Democracy and

Deep-Rooted Conflict: Options for Negotiators, pp. 191-204.

Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Reilly,

Benjamin. 2001. Democracy in Divided Societies: Electoral

Engineering for Conflict Management. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press. Reynolds,

Andrew. 12005. “Reserved Seats in National Legislatures: A

Research Note.” Legislative Studies Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 2,

pp. 301-10.. Reynolds,

Andrew. 1999. Electoral Systems and Democratization in South

Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Reynolds,

Andrew, Ben Reilly, and Andrew Ellis. 2005. Electoral System

Design: The New International IDEA Handbook. Stockholm:

International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Reynolds,

Andrew, and Ben Reilly. 1997. The New International IDEA

Handbook of Electoral System Design. Stockholm: International

Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. Royal

Commission of the Electoral System. 1986. Toward a Better

Democracy. Wellington, New Zealand: Government Printer. Rudd,

Chris, and Ichikawa Taichi. 1994.

“Electoral Reform in New Zealand and Japan: A Shared Experience?”

Working Paper No. 8, New Zealand Centre for Japanese Studies, Massaey, University. Rush,

Mark E., and Richard L. Engstrom. 2001.

Fair and Effective Representation: Debating Electoral Reform and

Minority Rights. Lanham, Md.: Rowman

& Littlefield. Safi, Louay. 1991.

“Nationalism and the Multinational State.” American Journal of Islamic

Social Sciences, Vol. 8, No. 2 (http://lsinsight.org/articles/1998-Before/

Nationalism.htm). Schneckener, Ulrich, and Stefan Wolff, eds.

2004. Managing and Settling Ethnic Conflicts: Perspectives on

Successes and Failures in Europe, Africa and Asia. New York:

Palgrave Macmillan. Schouls, Tim. 1996.

“Aboriginal Peoples and Electoral Reform in Canada: Differentiated

Representation versus Voter Equality.” Canadian Journal of Political

Science, Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 729-49. Seitz,

Brian. 1995. The Trace of Political Representation.

Albany: State University of New York Press. Shugart, Mathew Sobert,

and Martin P. Wattnberg, eds. 2001. Mixed-Member

Electoral Systems: The Best of Both Worlds? Oxford: Oxford

University Press. Sibbeston, Nick G. n.d. “Guaranteed Parliamentary Representation for

Aboriginal Peoples” (http://sen.parl.gc.ca/nsibbeston/new_page_1.htm). Sisk,

Timothy D. 1996. Power Sharing and International Mediation in

Ethnic Conflicts. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of

Peace Press. Sisk, Timothy D.,

and Andrew Reynolds, eds. 1998. Elections and Conflict

Management in Africa. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of

Peace Press. Sorrenson, K.

1986. “A History of Maori Representation in Parliament,” Printed as

Appendix B to Royal Commission of the Electoral System’s

Toward a Better Democracy. Wellington, New Zealand: Government

Printer. Sullivan, Ann, and Dimitri Margaritis.

2002. “Coming Home? Maori Voting in 1999,” in

Jack Vowles, Peter Aimer, Jeffrey Karp, Susan Banducci, Raymond Miller, and Ann Sullivan, eds. Proportional

Representation on Trial: The 1999 New Zealand General Election and the Fate of

MMP, pp. 66-82. Auckland: Auckland University Press. Sullivan, Ann, and

Jack Vowles. 1998. “Realignment? Maori

and the 1996 Election,” in Jack Vowles,

Peter Aimer, Susan Banducci, and Jeffrey Karp, eds.

Voters’ Victory? New Zealand’s

First Election Under Proportional Representation, pp. 171-91. Auckland: Auckland University Press. Taagepera, Rein, and Matthew Soberg Shugart.

1989. Seats and Votes: The Effects and Determinants of Electoral

Systems. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. Thelen, Kathleen, and Sven Steinmo. 1992. “Historical Institutionalism

in Comparative Politics,” in Sven Steinmo, Kathleen

Thelen, and Frank Longstreth,

eds. Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in

Comparative Analysis, pp. 1-32. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. Varma, Deepa.

2003. Good Governance through Diversity: Mixed Member Representation

in India. Hyderabad, India: Foundation for Democratic Reforms. Venice

Commission (European Commission for Democracy Through law). 2000.

“Electoral Law and National Minorities” (http://www.venice.coe.int/docs/2000/CDL-

INF(2000)004-e.html). Waitangi

Tribunal. 1994. Maori Electoral Option Report. Wellington:

Department of Justice (http://www.knowledge-basket.co.nz/oldwaitangi/text/wai413/toc.html). Ward, Alan. 1999. An

Unsettled History: Treaty Claims in New Zealand Today. Wellington:

Bridge Williams Books. Williams,

Melissa S. 1998. Voice, Trust, and Memory: Marginalized Groups

and the Failing of Liberal Representation. Princeton: Princeton

University Press. Young,

Iris Marion. 2000. Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford:

Oxford University Press. Zvulun, Jackey.

2004. “Implementation of STV in 2004 New Zealand Elections.” Paper

presented at the Australian Political Studies Association Conference,

University of Adelaide, September 29-October 1. * 發表於原住民同舟協會主辦「原住民族立委選制的展望研討會」,台北,台灣大學校友會館,2005/11/26。 對於原住民族代表性的綜合討論,見Archer(2003)、Iorns(2003)、以及Sibbeston(n.d.);有關加拿大,見Fleras與Elliott(1992: 90)、Hunter(2003)、Kinght(2001)、以及Schouls(1996)。 所謂的排除,Young(2000: 52-57)分為外部排除(external exclusion)、以及內部排除(internal exclusion),前者是指赤裸裸地排除在決策的過程,後者是指雖然允許進入體制,卻發現自己的看法不是被忽視、就是被嗤之以鼻,因此,仍然是一種支配的關係。 根據Williams(1998: 19),公義是實質的目標,而公平(fairness)是程序上的手段。至於所謂的公義,是指沒有支配(domination)、沒有壓迫(oppression),正面來看,也就是自決(self-determination)、以及自我發展(self-development)的境界(Young: 2000: 31-33)。 前身為在1973年於赫爾辛基開議的「歐洲安全暨合作會議」(Conference on

Security and Cooperation in Europe,簡寫為CSCE),在1995年才改為「歐洲安全暨合作組織」(Organization for

Security and Cooperation in Europe,簡寫為OSCE);OSCE下轄的「少數族群高級公署」(High Commission on National

Minorities,簡寫為HCNM) 成立於1993年,主要的功能在針對族群衝突作預警式的監控、並尋求可能的化解之道。 自治的英文用字包括self-rule、self-government、以及autonomy。自治的方式包括地域式的(territorial)、以及非地域式(non-territorial)兩種;後者可以說是一種屬人的自治(personal autonomy)、或是文化性的自治(cultural autonomy)。Frowein與Bank(2000)另外區隔出功能性自治(functional autonomy),強調的是自願結社:參見施正鋒(2005: 243-48)。 有關於選舉制度的文獻很多,見Dummett(1997)、Farrell(1997)、Gay(1998)、Lijphart與Grofman(1984)、Návrat(2003)、Nurmi(1987)、以及Reeve(1992)。 另外,「彌補性投票」(supplementary vote、簡寫為BV)用於斯里蘭卡的總統選舉,是限定只寫1、2的偏好,如果沒有人獲得過半的最佳偏好(也就是1),那麼,只保留得票最高的二個候選人,然後,將投給其他候選人的票的第二偏好分給二人(Gay,

1998: 67)。此制適用簡單的偏好投票來取代二輪桃票。 介於兩者之間的是「累積投票」(cumulative vote),過去用於美國伊利諾州的眾議員選舉,最大的特徵是在復數選區之下,選民可以重複投給同一個候選人,因此,是用連記的方式連達偏好;見Blair(1960)。 另外,「限制連記」(limited vote、簡寫為LV)也可以算是一種半比例代表制,也就是在複數選區之下的多數、或是過半數決,選民必須同時分別投多個候選人,卻不像全額連記一般可以投等額的票數,多用於地方選舉、或是西班牙的參議原選舉(Reynolds,

et al.: 2005: 117)。 廣義的混合制是指外形、或是選舉過程看起來像是由兩部分加起來的選制,也就是所謂的兩票制(two-vote system),因此,把混合比例制都算是混合制,通稱為MMP;見Farrell(1997)、Shugart與Wattenberg(2001)、以及Reynolds等人(2005: 28)。 Blais與Massicotte(1996: 68-72)分別稱之為機械效應、以及心理效應。有關於選舉制度的政治效應,見Grofman與Lijphart(1986)、Lijphart(1994)、Rae(1967)、以及Taagepera與Shugart(1989)。 這一部分的文獻較多,譬如Grofman(1998、1990)、Grofman與Davidson(1992)、Grofman等人(1992、1982)、Guinier(1994)、McKay(1970)、以及Ruch與Engstrom(2001)。 有關於毛利選民的政黨認同變動,尤其是在1980年代於工黨政府的不滿,見Sullivan與Margaritis(2002)、以及Sullivan與Vowles(1998)。有關1868年以來的毛利國會議員的名單,見http://www.ps.

parliament.govt.nz/schools/texts/maorimp.shtml。 這一部分,我們主要根據Iorns(2003)、MMP Review Committee(2001)、Jackson與McRobie(1998)、Waitangi Tribunal(1994)、Royal Commission on the

Electoral System(1986)、Sorrenson(1986)、Chapman(1986)、以及Fleras(1985)。 此時,如果屆齡的毛利男人符合財產條件,同時也可以參與一般選區的投票,一直到1893年才廢止;從1896年起,具有50%血緣的毛利人可以在毛利選區、以及一般選區擇一投票(RCES, 1986: 83)。 由五百多名毛利人酋長與英王在1840年所簽定,確立了毛利人權利的基礎;不過,往往被白人墾殖者片面解釋為毛利人從此接受英國殖民統治,也就是同意以主權的讓渡來交換英國的保護、土地、森林、漁獲、以及其他財產的所有權(Ward, 1999)。 皇家選舉制度委員會(RCES,

1986: 88-89)特別指出,毛利國會議員必須有下列特徵,包括會說流利的毛利語、服務毛利社區的紀錄(譬如致力於保存毛利文化認同)、以及在部落有起碼的地位或評價(也就是處理毛利事務的經驗)。 根據1975年的『選舉修正法』,毛利選民在每回人口普查之後,可以自願選擇在毛利人名冊(Maori Roll)、還是一般人的選舉名冊(General Roll,原稱為歐洲人的選舉名冊European Roll)上來登記,稱為「毛利選擇」(Maori Option)(RCES, 1986: 83)。 另外,一直要到1967年,毛利人才可以到一般選區當候選人;見http://www.ps.parliament.govt.nz/schools/

texts/maorimp.shtml。 有關毛利選區劃分的原則如下:原有選區、毛利部落所構成的共同體、交通設施、地理特徵、以及毛利選民的推測;見http://www.aceproject.org/main/english/1f/1fy_nz.jtm。 唯有「消費者暨納稅人黨」(ACT、簡稱Association of Consumers and

Taxpayers)主張廢除毛利席次,除了說行政上的不便、以及亂劃選區的誘惑以外,特別選區的做法意味著毛利人需要人家保護的恩賜態度(patronage);見(MMPRC, 2001: 21)。 |