|

National

Identity and National Security:The Case of Taiwan* |

||

|

Cheng-Fong, SHIH Department

of Public Administration, Tamkang University,

TAIWAN |

||

|

Introduction

For more than half a century, national security policy has been largely

understood as national defense policy, given Chinese irredentist claim over

Taiwan’s sovereignty. In the past

decade, while Taiwan has mainly liberated itself from the party-state rule

under the Kuomintang (literally Chinese Nationalist Party), it has yet to

consolidate its new gained democracy.

Three crucial tasks have to be undertaken: forging national identity,

integrating ethnic cleavages, and reconstructing political institutions. Among the three, dubious national

identity, that is, being Taiwanese or Chinese, would complicate how Taiwan

may perceive its national security and make its security policy.[1][1]

In the past, it had been expected that while political rivalries in

the home front may have made the choice of security strategy intractable,

external threats from China, military and vocal, on the other hand, would

actually compel all political forces in Taiwan to mend their differences and

to converge their national identity. Given the 1995-96 missile crises, this

line of argument seemed to have prevailed. However, latest Chinese economic

maneuvers targeted at Taiwanese businessmen (台商) impel us to consider possible

other sources of threat to security.

In this study, we will start with the development of a conceptual framework

for national security, where national identity will have recursive impacts:

while one’s national identity will decide one’s perception of national

security, one’s comprehension of security and threat would prompt one to

reconcile one’s own national identity.

Secondly, we will endeavor to clarify the unnecessary equivalence of

“national identity” with “state identity,” which in turn has made political

Taiwanese [state] identity unfortunately entangled with cultural Chinese

[national] identity. Thirdly, we

will how the causal link between national identity and to national security

is intermediated by some other factors in the case of Taiwan. Conceptual

Frameworks for National Security

The development of National Security studies has generally followed that of

International Relations theory, that is, the three “great debates”: idealism

vs. realism, realism vs. behaviorism, and positivism vs. post-positivism

(Smith, 1995: 14-15). McSweeny (1999) thus arrive at four phases of Security

Studies: political theory, political science, political economy, and

sociology, with respective focus on common security, strategy,

international/comprehensive security, and human security. The last phase, starting with the

early 1990s, would focus how perception would have impacts on security, and

accordingly emphasize the importance of identity and security construction.

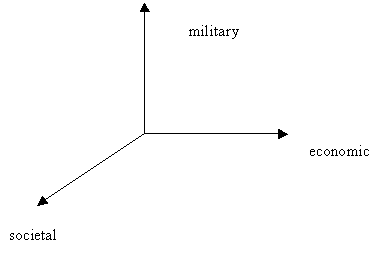

In retrospection, we can generalize that the concept of security has

developed along two dimensions: sources of threat, and subjects of

security/targets of threat. While

the former would enlarge from politics, military, economy, environment, and

to society, the latter would deepen from national, international, and to

human. Alternatively, we may have

a third dimension of security, that is, whether it is characters or

relationships. In this fashion,

security may contain both objective physical configurations and subjective

mental conditions; while the former denotes being free from physical threats,

the latter stands for feeling secure (Snow, 1998).

McSweeney (1999: 14-15) similarly classifies the

concept of security into positive and negative ones. Traditional notions of security tend

to take a negative form, that is, avoiding physical

threats. In this sense, security

is something tangible, observable, and measurable. By so conceptualized, the concern of

security is how to mobilize physical resources in order to counter external

threats, guarantee territorial integrity, and preserve domestic

institutions. In other words,

national security, at least in the short run, is tantamount to military

defense. On the other hand,

positive security is conceived as relationship, which is a human construction

as reflected in stable or changing collective identity. McSweeney

(1999: 17) terms it as “ontological security,” and further breaks it down

into self, social capabilities, and confidence to deal with others. In this broad definition, insecurity

is threat to values or identity (Tickner, 1995:

180). Accordingly, a long-term

contemplation of national security has to take national identity into

account.

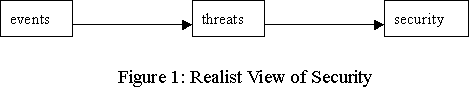

According to the state-centric conception in realism, the subject of security

is the state. Therefore, the

supreme goal of security is to guarantee national security against external

threats. Since the international

system is deemed as a status of anarchy, in order to uphold

self-preservation, the state has to rely on military forces (Waltz, 1979). Under such a framework, a state’s

capacity of security is measured by its military capabilities relative to its

opponents (Figure 1).

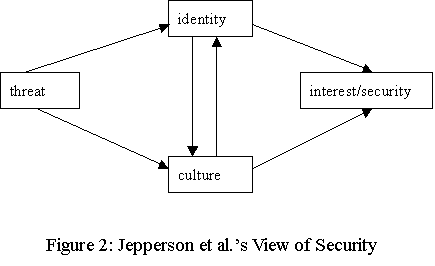

Based on the tenets if neo-liberalism, Jepperson,

Wendt, and Katzenstein (1996) argue that whether an

event is considered as threat is contingent upon the definition of national

interests, which in turn would decide what constitutes proper security policy

is and what adequate actions to take.

Therefore, while the above framework may be succinct, its fails to take

societal factors into account, especially those national identity and

norms/culture[2][1] environments that may influence a

state’s survival, behavior, and characters (Jepperson

et al., 1996: 35-36). Taking a

constructivist approach, they take note not only that national identity would

have impacts on norms/culture, bust also that

culture would determine the formation of national identity (pp. 52-53). We thus have a revised framework of

security (Figure 2).

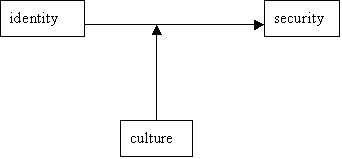

While agree with Jepperson et al. that national

security is decided by collective identity, particularly when members of the

state fail to agree upon the contents of national identity, Wendt (1994) and

Campbell (1998), taking a similar perception approach, would underline the

importance of identity, rather than norms or culture. According to the interpretation of Ktazenstein (1996: 19-22), norms and culture are at best

interpreted as contexts of security policy. Therefore, the independent variable

for security that Jepperson et al. (1996) have

introduced is identity. We thus

have the revised Figure 3.

Figure 3: Revised Perception View of Security

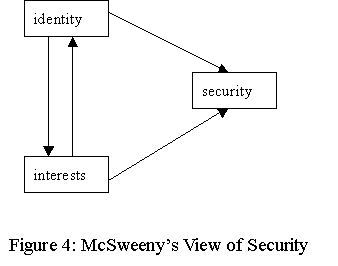

Challenging the conception of security by the once dominant realism, McSweeny (1999: 214) arguer that even though states, as agents,

may be not in a position to change the fundamental structure of the

international system, they at least possess the opportunity to decide whether

to accept or to reject it.

Still, he considers it that both Wendt (1994) and Campell

(1998) overstate the explanatory utility of perception, be it in the form of

identity or cultural factors, and thus proposed that national interests need

to be taken into account (p. 135).

On the other had, while admitting that

neo-functionalism may have recognized how interests would affect how we

choose our identity, he deems interests nothing but opportunity rather than

“seductive enmeshment” (McSwweny, 1999: 167-72,

195). In a nutshell, even though

both perception and neo-functional approaches attempt to surpass realism,

they overstate the explanatory utility of identity and interests

respectively; in other words, identity and interests are mutually

constructing each other, and thus in turn decide how security is perceived

(pp. 123, 214). We hence depict McSweeny’s revised view of security in Figure 4.

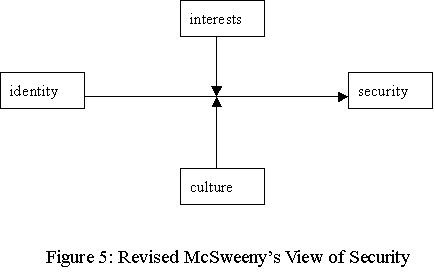

While generally agreeing with McSweeny (1999: 398)

that identity is the base for interests and security, we have reservations

regarding how interests may have recursively affect the choice of identity.[3][1]

After all, the interest mechanism that the European Union has exerted

on Ireland to accept peace agreement in Northern Ireland may not be

universally valid. In our view,

interests are at best an intermediary variable that may exacerbate or

mitigate the causal link between identity and security, rather than an

independent variable (Figure 5).

Culturally

National Identity and Politically State Identity

In English usage, as “national security” is equivalent to “state’s security,”

so is “national identity” to “state’s identity.” Nonetheless, there is no such an

isomorphism in Chinese (中文)/Hanji[4][1] (漢字). As a result, in the context of Taiwan,

“national identity” may be translated into both “nation’s

identity“ (min-chu-zen-ton, 民族認同) and “state’s identity“ (guo-chia-zen-tong,

國家認同), or

“identifying with the nation” and “identifying with the state”

respectively. While nation and

state are highly correlated, the two concepts obviously have different

connotations.

For two reasons,[5][2] substantive and semantic, the concept

of national identity in Taiwan tends to be understood as “state’s identity”

detached from “nation’s identity.”

For one thing, ordinary people are distasteful of the idea of nation

as it is reminiscent of the imposed official Chinese nationalism derived from

Sun Yat-sun’s Three

Principles of People (Sun-min-chu-i, 三民主義) in their days of high school under the KMT authoritarian

rule. Secondly, the elites

tend to interpret nationalism in its illiberal, chauvinistic, and expansionist

formats. As a result, concerned

scholars, contemplating to evade its pejorative denotations, have chose to use state in place of nation; and hence guo-chia-chu-i (國家主義, literally statism), instead of min-chu-chu-i (民族主義,

nationalism). Nevertheless, this

seemingly ingenious evasion becomes redundant when nation-state/nation’s state (民族[的]國家, min-chu-guo-chia)

has to be similarly translated into state-state/state’s

state (國家[的]國家, guo-chia-guo-chia).

At this juncture, national/citizen has to come to the rescue; and

hence guo-min-guo-chia

(國民國家,

nationals’ state)/gon-min-guo-chia (公民國家, citizens’ state). In

order to avoid this conceptual cloud, Ng (1998) transliterates nationalism as

na-hsiong-na-li-si-bun (那想那利斯文). Therefore, a political sense of

national identity would be preferably known as state identity, statist

identity, or identity of state.

Nonetheless, a cultural sense of “nation’s identity“ is

here to stay. People in Taiwan

tend to embrace a primordial conception of nation based on common ascribed

cultural traits,[6][3] which is essential and deterministic

and allows no room for subjective construction in Anderson’s (1991) sense of

collective imagination after common history, experience, or memory. As nation is narrowly understood as

the Han people (Han-min-chu/Han-zen, 漢民族/漢人), national identity would be confined to “naturally”

identifying with the Han people.

Since most people in Taiwan would accept the official doctrine that

they belong to the so-called “Chinese nation” (Chong-hua-min-chu, 中華民族), it is not surprising to discover that they tend to call

themselves中國人 (Chong-guo-zen,

ethnic Chinese), or more recently華人 (Hua-zen,

cultural Chinese). As a result,

while the Han people in China are included as compatriots (tong-bau, 同胞), the Aboriginal Peoples (Yuan-chu-min-chu, 原住民族) in Taiwan, culturally Austronesian and racially

Malayo-Polynesian, are excluded.

By so doing, national identity here is not only culturally determined

but also racially defined.

However, not only ethnic Chinese bust also Han people are a cultural

conglomerate constructed out of various racial stocks. By imaging themselves as “authentic”

Chinese, the Taiwanese are pursuing an oxymoron “pure hybridity.”

According to the tenets of realism, national identity is destined and

fixed. Alternatively, proponents

of constructivism would argue that national identity is formed after

interactions, negotiations, learning, definitions, and construction, which is

beyond the elites’ control (Katzenstein, 1996;

Wendt, 1992). Internally,

national identity in Taiwan has been intertwined with ethnic identity and

party identification (Shih, 2002).

As ethnic groups fail to reach consensus over formula for

resource-distribution and political parties quarrel among themselves over

rules of game for power-sharing, national identity (read state identity) is

apt to be mobilized as pawn of political competition. Ambiguous national identity has so far

developed along ethnic/party cleavages.

While the Mainlanders/Pan-blue supporters[7][4]

would consider themselves Chinese and Taiwanese as well (是中國人, 也是台灣人), in

any, the Natives/Pan-green supporter would deem themselves Taiwanese first

and Chinese second (是台灣人, 也是中國人). Of course,

there are also quite a few who consider themselves as Taiwanese only (是台灣人, 不是中國人), and

few who take themselves as Chinese only (是中國人, 不是台灣人).

It is noted that both of the terms “Chinese” and “Taiwanese” are not only

vague but ambiguous also. In

everyday life, Chinese may connote racial Han people, cultural Hua-zen, or political Chong-guo-zen.

Even though it is generally recognized that political Chinese means

nationals/citizens of the People’s Republic of China, the government of

Taiwan, under the official state name of the “Republic of China,” would

indoctrinate the Taiwanese to deem themselves as Chong-guo-zen without offering any confirming definition.[8][5]

It is no wonder that the passport of Taiwan only prints “Republic of

China” on its cover. While the

term Taiwanese has long been intentionally relegated as a regional one, it is

traditionally reserved for the Holos, the largest

ethnic group, or, more inclusively, the Natives (excluding the Mainlanders).[9][6]

Only recently have some Mainlanders begun to call themselves

Taiwanese, especially after they uncomfortably discovered that they had been

treated as “Taiwanese compatriots” (Tai-bau/Tai-wan-tong-bau, 台胞/台灣同胞) by the Chinese.

In ambivalence, they seem determined to retain the identity of

“Chinese from Taiwan” as the government appears satisfied with the

quasi-official state name “Republic of China on Taiwan.”

What has complicated the entanglement is the tendency that one’s ethnic

identity (Natives or Mainlanders) would largely decide one’s national

identity (Taiwanese or Chinese) and hence one’s attitudes toward the issue of

Taiwan’s future (Independence or Unification). Recursively, one’s ethnic identity is

also composed of one’s conception of national identity and/or Taiwan’s relations

with China in the future, especially for the Mainlanders (Shih, 2001). These mutually reinforced cleavages

are also conducive to disparate party identification.

In balance, the Taiwanese, by they

Natives or Mainlanders, have been engulfed in the intersection of a

culturally and racially defined Chinese national identity and a politically

defined Taiwanese state identity.

Externally, these dubiously interwoven national identities have led to

disparate attitudes toward China, the only enemy of Taiwan in the world

nowadays. National

Identity and National Security

Leaving aside external threats from

China, Taiwan has yet to face internal security threats resulting from

uncertain national identity.

Without reaching a certain minimal degree of national integration,

members of the state would ask: Whose security to stand guard over? Whose state to protect? What country to identify with? In other words, before we can decide

what national security is, we need to settle what our national identity is (McSweeny, 1999: 71-72; Tickner,

1991: 179-81). Those who agitate

for Taiwan’s unification with China would not protest China’s incorporation

of Taiwan.

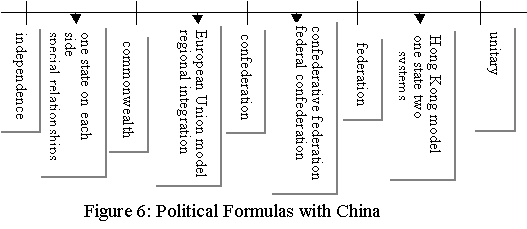

On the spectrum of political arrangements with China, more and more Taiwanese

would welcome a de jure independent Republic of Taiwan free from

China’s labyrinth if China promises to hand off Taiwan. Close to this position is former

President Lee Teng-hui’s (李登輝) “Two

States Discourse” (兩國論) which claims that “cross-strait relations as a

state-to-state relationship or at least a special [sui generis]

state-to-state relationship.” Next to this posture is

President Chen Shui-bian’s (陳水扁)

purposefully vague “New Center Line” (新中間路線). At one occasion when speaking to a

pro-independence audience through satellite transmission, the seemingly

undaunted president proclaimed that there is “One State on Each Side” of the

Strait of Taiwan (一邊一國論), probably to protect the base of his most staunch

supporters. However, at another

point, in order to appease China, he went so far as to pledged to embark on

economic and cultural integrations with China, and to seek for a framework

for perpetual peace and eventual political integration across the Strait of

Taiwan; and hence the so-called “Integration Discourse” (統合論). It would be fair to state that what

Chen has in mind is a kind of Chinese Commonweal made up of two “Two Chinese

States” (兩個華人國家), opting for institutionalized separation.

On the other end of the continuum, only those few true believers of Chinese

irredentism would embrace outright union with China, whether under “One

State-Two System formula (一國兩制, or Hong Kong model) or unitary system. Even though federation (聯邦),

confederative federation (邦聯式聯邦), and federal confederation (聯邦式邦聯) have been

proposed by pro-China politicians and scholars, the nearest stand is “Two

States in One Chinese Nation/Cultural China” (一個民族兩個國家/文化中國, or 一族兩國)

espoused by some Chinese loyalists in the KMT. What they envision is eventual

unification between Taiwan and China, generally known as “Germany Model” (德國模式). However, sensible policy strategists

in the KMT would only venture out the idée of a confederation (邦聯)

composed of the PRC and the ROC.

Finally, James Soong (宋楚瑜) of the PFP, imitating the experience of the European Union,

has so far cautiously proposed a “Roof Discourse” (屋頂論)

. While literally preaching an

image of two families under one roof, it is not clear whether he suggest an

eventual federation, confederation, or simply commonwealth. What they share is a desire to

design certain modus operandi in order to obtain eventual association

of China and Taiwan in whatever formulas.

If military threat is too provocative and national appeal is too latent to

provide Chinese any immediate satisfaction in the direction toward political

association between China and Taiwan, meanwhile, a more discursive and yet

effective approach has been launched lunched on Taiwanese businessmen in

China, that is, “Bullying Officials with Civilians” (以民逼官),

“Pressing Politicians with Businessmen” (以商逼政), and “Promoting

Unification with Three Links[10][1]” (以通促統). On this economic front, Idealism/Neo-Liberalism has its say on

policy recommendations. A related

preference is “Westward Policy [to China]” (大膽西進) in the spirit

of functionalism, understood as a ramification of the Idealism/Liberalism

camp. Inspired by the development

of integration in West Europe, its proponents have preached that trade and

economic cooperation with China may eventually be conducive to the ease of

political rivalry and military conflict between Taiwan and its Chinese

adversary. Nonetheless, the

cleavages between the two are not confined to territorial disputes only. Underneath Chinese hostility toward

Taiwan is its violent opposition toward Taiwan’s legitimate existence in the

international society, which is not going to pass into oblivion because of

economic exchanges. In addition,

as there exist enormous socio-economic disparities

and disproportion in territorial size between Taiwan and China, disparate

from those between France and Germany, any vulgar analogy is bound to shut

one’s eyes to the issue of vulnerability resulting from Taiwan’s economic

dependency on China. Diametrically different are the prescriptions offered by

Realists/Neo-Realists. Wary of

economic security on Taiwan’s part, former President

Lee Ten-hui (李登輝) espouses a Neo-mercantilist

economic policy toward China, “Restraining Hasty Investment [in China]” (戒急用忍). Given the fact that China the only

country is the world that has openly waged military threat against Taiwan,

Lee’s purposeful selection of trade restraints is understandable. Nevertheless, the current ruling

Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which came to power in May 2001, has

adjusted Taiwan’s thus far protective economic

stance toward China from “Moving Westwards [to China] While Strengthening the

[economic] Base [in Taiwan]” (強本西進) to “Actively Liberalizing [economic interactions with China]”

(積極開放) in

the name of adjustments to globalization, probably under the ceaseless

pressure from Taiwanese businessmen who expect to gain from direct links with

China.[11][2]

Some, apprehended by the conception of Neo-functionalism, have gone so

far as to aspire the eventual goal of political

unification with China as a result of deepened economic integration. Conclusions

So far, China has waged threats to Taiwan’s national

security in three dimensions: while deploying offensive missiles across the

strait of Taiwan at an alarming rate to coerce Taiwan into accepting its “One

China Precondition” (一個中國原則) after the Hong Kong Model, it has painstakingly enlisted

national sentiments to court those Taiwanese who share some racial-cultural

ethnic Chinese identity, and, at the same time, untiringly attracted

Taiwanese businessmen to move their plants to China with cheaper labor and

land.

Anxious to enter into a peace with China, President Chen appears confident to

deepen Taiwan’s economic interdependence, if not dependence, with China. In his optimistic calculation,

economic integration seems to promise pacifism as the case of European Union

has testified to the amicable relations between Germany and France. Self-styled as “Taiwan’s Nixon,” he

anticipates that his native-son identity would make his immune from the

accusation of Taiwanese traitor (台奸, Dai-gan). Having this essential conception of

national identity in mind, it is not surprised that he should ridicule the

KMT candidate of Taipei mayoral election Ma Ying-jeou

(馬英九)

contaminated with “Honk Kong Feet” (香港腳, athletic feet), implying this Hong

Kong born Mainlander is expecting to become governor of Taiwan under China’s rule (特首). By capitalizing

the coterminous relationship between ethnic identity and national identity,

he was unmistakably playing ethnic mobilization clothed in rhetoric of

national identity. By alienating

the Mainlanders, international or not, the DPP government is jeopardizing Taiwan’s

societal security.

Recalling that how a I-lan (宜蘭) born

military defector Lin Yi-fu (林義夫), who

had received a Ph.D. from University of Chicago and is now teaching at

Beijing University, had almost been acclaimed as a successful native

Taiwanese residing China before the Ministry of National Defense pledged to

charge him with high treason, we have witnessed how regional attachment is

still playing a major part in identity-formation among the Taiwanese. As the armed forces are

grumbling over for whom to fight, Taiwan cannot secure its military security

without reconciling its national identity.

Last year, the DPP government finally lifted its ban on investment in China’s

semiconductor industry by Taiwanese companies. While it is true that two of the

largest semiconductor companied which have energetically lobbied for

legalizing the already-made investment are run by Mainlanders, we must not

neglect the fact that two of the most enthusiastic promoters of direct links

with China are owned by native Taiwanese, who, somewhat naively, believe that

economy can be separated from politics and that security is the

responsibility of the government.

It may be exaggeration to state that these businessmen have not

motherland. In the age of

globalization, the phenomenon of diaspora has unleashed unlimited imagination

of national identity.

Nonetheless, it would be unfair to charge the former as traitors while

forgiving the latter’s banal ignorance.

In time, economic interests have to be attuned with national security

as defined by national identity.

In the end, a quick test of Taiwanese identity is whether how the Taiwanese

deem China, to borrow the words of Vice President Annette Lu (呂秀蓮),

enemy, fried, or motherland, which in turn will determine how national

security is contemplated in opposition to China. 《References》 Anderson, Benedict. 1991. Imagined

Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Rev.

ed. London: Verso. Campbell, David. 1998. Writing Security: United States

Foreign Policy and the Politics of Identity. Rev. ed. Manchester: Manchester University

Press. Chong, Chiu-hui (鍾秋慧), 2001。Cultural Dimension of National Security (國家安全的文化面),

master thesis, Taipei: Department of Political Science, National Taiwan

University. Jepperson, Ronald L., Alexander Wendt, and Peter J. Katzenstein. 1996. “Norms, Identity, and Culture in

National Security,” in Peter J. Katzenstein, ed. The

Culture of National Security: Norms and Identity in World Politics, pp.

33-75. New York: Columbia

University Press. Katzenstein, Peter J.

1996. “Introduction:

Alternative Perspectives on national Security,” in Peter J. Katzenstein, ed. The Culture of National Security:

Norms and Identity in World Politics, pp. 1-32. New York: Columbia University Press. McSweeny, Bill. 1999. Security, Identity and Interests: A Sociology of International Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Mattli, Walter.

2000. "Sovereign

Bargains in Regional Integration."

International Studies Review, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 149-80. Mattli, Walter.

1999. The Logic of

Regional Integration: Europe and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Moravcsik, Andrew.

1993. "Preference and

Power in the European Community: A Liberal Intergovernmentalist

Approach." Journal of

Common Market Studies, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 473-524. Ng, Chiau-tong

(黃昭堂), 1998. Taiwan Nationalism (台灣那想那利斯文). Taipei:

Vanguard (前衛出版社). Rosamond, Ben. 2000. Theories of European Integration. New York: St. Martin's Press. Shih,

Cheng-Feng (施正鋒), 2003. Taiwanese

Nationalism (台灣民族主義). Taipei: Vanguard (前衛出版社). Shih,

Cheng-Feng, 2002. “Ethnic Identity and National

Identity: Mainlanders and Taiwan-China Relations.” Paper presented at the International

Studies Association 43rd Annual Convention. New Orleans, March 24-27. Shih,

Cheng-Feng, 2001. “National Identity and Foreign Policy:

Taiwan’s Attitudes toward China.”

Paper presented at the International Studies Association 42nd

Annual Convention. Chicago, February

20-24. Shih,

Cheng-Feng (施正鋒), 2000. Taiwanese

National Identity (台灣人的民族認同). Taipei: Vanguard. Shih, Cheng-Feng (施正鋒), 1998. Ethnicity and Nationalism: Political

Analysis of Collective Identity (族群與民族主義:集體認同的政治分析). Taipei:

Vanguard (前衛出版社). Smith, Anthony D. 1986. The

Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Smith, Steven. 1995. “The Self-Images of a Discipline: A

Genealogy of International Relations Theory,” in Ken Booth, and Steven Smith,

eds. International Relations

Theory Today, pp. 1-37.

Cambridge: Polity Press. Snow, Donald M. 1998. National Security: Defense Policy

in a Changed International Order. 4th ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Tickner, J. Ann.

1995. “Re-visiting

Security,” in Ken Booth, and Steven Smith, eds. International Relations Theory

Today, pp. 175-97. Cambridge:

Polity Press. Waltz, 1979. Wendt, Alexander. 1994. “Collective Identity Formation and the

International State.” American

Political Science Review, Vol. 88, No. 2, pp. 384-96. Wendt, Alexander. 1992. “Anarchy Is What States Make of It:

The Social Construction of Power Politics.” International Organization,

Vol. 46, No. 2, pp. 391-4225. Weston, Burns H.,

ed. 1990. Alternative Security: Living

Without Nuclear Deterrence.

Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. |