|

State Power and Globalization: Adjustments of Taiwan’s Agricultural

Policy under the WTO* |

||

|

Cheng-Feng Shih and Pei-Ing Wu** |

||

|

Introduction Under the dominant explanatory epistemology, two rationalistic approaches have dominated the field: while Liberalism/ Neo-Liberal Institutionalism would empathize how a state may seek to strategize its policy in an institutional setting, Realism/Neo-Realism would posit that a state’s policy is decided by its position in the international system. In this study, we would adopt a constructive approach by examining how Taiwan, as an agent, may have pondered over interacting with the structure, defined here as the systemic social norm of free trade under the World Trade Organization (WTO). As Taiwan has long been isolated in the international stage, it has to construct its national identity and understand its national interests within the emerging social context in the age of globalization, when the state has to adjust its functions. With this understanding, the new global norms are no longer perceived as merely constraints or accelerators of Taiwan’s foreign policy behavior. Rather, Taiwan is endeavoring to challenge the international political structure of no-recognizing Taiwan by being actively engaged in the WTO, alternatively perceived as the Economic United Nations. Hence, Taiwan is adjusting its agricultural policy from protective input subsidies and price supports to direct payments to the farmers. Conceptual

Framework/Theoretical Considerations

In the field

of International Relations, foreign policy determinants are usually found in

three levels of analysis (or images): individuals, states, and the system (Waltz,

1959). While this way of

classifying explanatory variables is heuristically convenient, it is

inescapably state-centered, in the sense that these variables are enlisted to

account for a state’s

inside-out foreign policy behavior and thus fail to take into account those

approaches that would emphasize system-centered phenomena (Caporaso, 1997: 565). A more serious

detrimental deficiency is that the arbitrary divide[1][1] has led to two camps of ontologically

partial theories: while structuralism/determinism would give emphasis to

systemic factors and thus neglect other factors, reductionism/voluntarism

would underscore the importance of individuals’ rational choice (Caporaso, 1997: 565-66; Clark, 1999: 41). One may continue to pretend that there

are two separate arenas where the state may successfully play two roles at

the same time as possessing split personality. However, it is doubtful whether any

political actor can afford to such market segmentation, for instance, foreign

policy rhetoric for domestic consumption. Alternatively, we may take an

additive approach by reducing all social properties to individuals and their

interactions and then combining these parts and processes. Caporaso

(1997: 566) is keen to disapprove of this individualism as it has merely

substituted “social accounting” for theoretical explanations. A more fruitful

strategy would hinge on how we may successfully design a research agenda that

may integrate, or combine both international and domestic politics

simultaneously. We may classify

various attempts at synthesis across International Relations and Comparative

Politics into two broad approaches: decision-making, international

society/world system, and structuration/constructivist theories.[2][2]

Within the decision-making framework, two models have been empirically

productive: Second Image Reversed and Two-level Game. As vividly distinguished by Caporaso (1997), while Second Image suggests domestic

causes of international effects, Second Image Reversed advances international

causes of domestic effects. For

proponents of Second Image Reversed, such external/international factors as

globalization and internationalization are perceived as opportunity,

incentive, or barrier, and thus employed to shed light on domestic policy adjustments

and political collations (Milner and Keohane,

1996). Accordingly, the causal

link identified here is only non-recursive outside-in one. Another popular

decision-making approach is Two-level Game, where a Chief of Government

(COG), equipped with his own utility function, has to play two games at two

different levels, treating both the international system and domestic

constituencies as resources and constraints (Putnam, 1988; Moravcsik, 1993).

Even though Caporaso (1997: 567)

dissatisfiedly comments that it is more a metaphor rather than any

explanatory approach, it nonetheless points to the intersection of

international and domestic influences at the Janus-faced state, the roles of

which deserve our further exploration in a later section. A second approach

takes the international society or the world system as a holistic

configuration, where the state has to find out its own comfortable

place. Seemingly

structuralism in form, models of this sort are inclined to take a domestic

analogy and thus espouse “domestification of international

politics,” to borrow the term

coined by Caporaso (1997). While underlining the overarching

maneuvering at the systemic level and thus somewhat rendering the state as a

residual category, it has intrinsically provided another non-recursive

causal, if any, outside-in link.

Nevertheless, if comprehended differently but not diametrically, it

may enlighten us how profound changes at the systemic level, whether globally

or regionally, may have challenged the states’ capabilities. One last approach on

the list takes an ontologically structuration perspective toward the

agent-structure dialects, that is, they both are parts of the

their relations and thus are mutually constituted (Wendt, 1987; Checkel, 1998; Hopf, 1998;

Barnett, 1999). Analytically, the

state is conceived as a broker between society and the international system,

thus integrating domestic politics and international politics;

methodologically, the state, by becoming the common ground, or “frontier” suggested by Rosenau (1996), for national politics and foreign policy,

serves as a convergence of Comparative Politics and International Relations.

(Clark, 1999: 2, 17). More specifically, both internal

democratization and external globalization would determine a state’s interests and

capabilities; and by interacting with both society

and the international system, the state is bound to construct its identity

(Clark, 1999: 57-58). The

approach is accordingly considered epistemologically[3][3] constructivist. In a nutshell, we

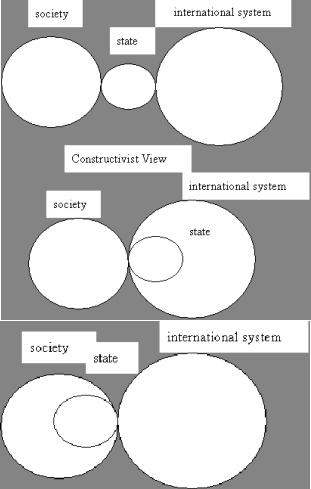

have come with three views of the state (see Figure 1): while structuralists would deem the state as subsumed by the

international system, and reductionists tend to perceive the state more

attuned with its domestic constituencies, constructivists would allow for the

state’s two-front

maneuvering, depending on how much power it possesses.

Figure 1: Three Views of the State Policy

Predispositions for Taiwan In terms of policy predispositions, while Neo-Realism would predict that a state’s foreign behavior is compelled externally by the overriding force of the international system, and Liberal-Institutionalism would allow for far more policy leverages to be exercised by the state. On the other hand, constructivism would predict that the state enjoys the liberty to engage with both domestic constituencies and external/international powers. In the following, we will illustrate how these three perspectives would direct different policy predispositions for Taiwan in calculating its national interests. Since the end of World War II, the national

interests of Taiwan have been largely defined by how it has successfully

guarantee its national security as Communist China has never ceased coveting

over Taiwan’s territory in military terms. At different stages, various national

security strategies have been suggested or implemented in Taiwan, which may

be understood from either Realist or Idealist perspective in International

Relations theories.[4][4] From the vintage point of Idealism, especially its Neo-liberal Institutional vein, collective security mechanism, global or regional, may be warranted to deter the expansionism of potential aggressors with military pacification. However, because of the obstruction from Russia and China, who possess the veto power within the Security Council of the United Nations, the universal application of the collective security instrument has unfortunately so far been circumscribed. For the past decade, Taiwan has persistently sought to reenter/join the UN, ostensibly in the hope to walk out of international isolation imposed by China. In fact, one of the most important considerations is to internationalize the peace and security of the Taiwan Straits by actively taking part in the happenings in the international society. Again, because of the uncompromising boycott by China, Taiwan has so far failed to make its telling presence in the UN arena, not to mention the application of UN collective security measure just in case China should wage a war against Taiwan. On the extreme of the ideological spectrum is

Realism in various shades, that is, how to obtain self-help through

balance-of-power in the anarchic international system (Waltz, 1979), and to

safeguard national security, conceived as military power, through forming

defensive alliance. During the

Cold War era, the US managed to forge bilateral and multilateral military

alliances with its allies all over the world to contain the Communist

bloc. Within that bipolar

competition buttressed by nuclear capabilities, Taiwan’s security was

essentially guaranteed through its Mutual Defense Treaty with the US.[5][5]

Although the US was forced to terminate its formal military and then

diplomatic relations with Taiwan in the 1970s, a Taiwan Relations Act[6][6] was passed by was US Congress to

maintain continuous relationship with Taiwan in 1979. Even though the US has deliberately

avoided any explicit military commitment to defend Taiwan, the peace-enforcement

stipulations implied within the TRA framework have rendered the US-Taiwan

relations into some quasi-military alliance as testified in the 1995-1996

missile crises across the Taiwan Straits. And, the Guidelines for Japan-US

Defense Cooperation[7][7] promulgated in 1997 was

perceived for military consolidation in order to maintain acceptable

balance-of-power in East Asia, if no to contain China. On the

economic front, Idealism/Neo-Liberalism has its say on policy

recommendations. A related preference

is “Westward Policy” in the spirit of functionalism, understood as a

ramification of the Idealism/Liberalism camp. Inspired by the development of

integration in West Europe, its proponents have preached that trade and

economic cooperation with China may eventually be conducive to the ease of

political rivalry and military conflict between Taiwan and its Chinese

adversary. Nonetheless, the

cleavages between the two are not confined to territorial disputes only. Underneath Chinese hostility toward Taiwan

is its violent opposition toward Taiwan’s legitimate existence in the

international society, which is not going to pass into oblivion because of

economic exchanges. In addition,

as there exist enormous socio-economic disparities

and disproportion in territorial size between Taiwan and China, disparate

from those between France and Germany, any vulgar analogy is bound to shut

one’s eyes to the issue of vulnerability resulting from Taiwan’s economic

dependency on China. Diametrically

different are the prescriptions offered by Realists/Neo-Realists. Wary of economic security on Taiwan’s

part, former President Lee Ten-hui espoused a

Neo-mercantilist economic policy toward China. Given the fact that China the only

country is the world that has openly waged military threat against Taiwan,

Lee’s purposeful selection of trade restraints is understandable. Nevertheless, the current Democratic

Progressive Party (DPP), which came to power in May 2001, has adjusted

Taiwan’s thus far protective economic stance toward China, probably under the

ceaseless pressure from Taiwanese businessmen who expect to gain from direct

links with China.[8][8]

Some, apprehended by the conception of Neo-functionalism, have gone so

far as to aspire the eventual goal of political unification

with China as a result of deepened economic integration. Alternatively,

we argue that accession to such a non-political international organization as

the WTO had long been contemplated one paramount mission in order to break off

the international isolation under the Hallstein

doctrine imposed by Chinese since declining international status would

jeopardize the government’s legitimacy.

Taiwan, as an agent, however, is not at the mercy of the international

structure. On the contrary,

Taiwan is redefining its national interests and reconstituting its national

identity by wholeheartedly embracing any international organizations that do

not require membership in the United Nations. In the case of the WTO, economic

concessions are interpreted as a necessary cost for the de facto

recognition of Taiwan’s existence in the world stage. Accordingly, protective agricultural

policy proscribed by the current norm of free trade under the WTO has to be

phased out at all costs. As a

result, direct payments to the rice farmers are replacing various input

subsidies and price support (LIN and WU, 2000; WU and LIN, 2000).[9][9] The Evolving State Given

the new international order of globalization, while a few have hastily

heralded the end of the state,[10][10] some would admit that many states in

the Third World are at best qualified as quasi-states in the sense that they

are unable to manage, at least, economic affairs in the age of economic

interdependence and internationalization (Jackson and Sørensen,

1999; Jackson, 1990). Still,

there is a growing consensus that it is the declining importance of territorialization rather than the decline of the states

per se. Therefore, the

state has to transform itself for survival (Clark, 1999: 36-37).[11][11]

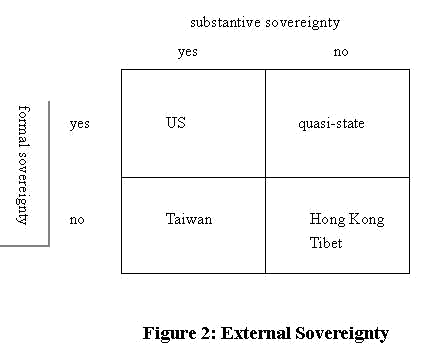

In our constructivist understanding, the pivotal role the state plays

is contingent upon its power.

A state’s power/strength is

defined by both its external sovereignty in the international society, and

its internal autonomy when facing society (Clark, 1999: 57-58). Since the

Republic of China/Taiwan was force to withdraw itself from the UN in 1991, it

has been rendered as a pariah in the world. In fact, after East Timor and

Switzerland are admitted into the UN, Taiwan becomes the only viable state

refused the UN membership. Even

if it may possesses substantive sovereignty in the sense that it has the

capacities to conduct interactions with other states, its formal sovereignty

is in the lacking given the fact that most states refuse to confer

recognition to Taiwan, which in turn deprives Taiwan of those claims to

membership in major international organizations and access to forthcoming

resources (Caporaso, 1997: 581). Meanwhile, although successive

governments of Taiwan have claim that Taiwan/

Republic of China is a sovereign independent state in every sense, its

sovereign rights are precarious.

In other words, Taiwan, as a political entity,[12][12] may have enjoyed de facto

sovereignty, but it still in need of de jure sovereignty to be

validated by the international society. On the other hand, while Taiwan’s formalistic state authority is problematically contested, the state has long substantive autonomy/strength when facing the society.[13][13] In the minimum, the strength of a state is measured by the degree how it may wage political control over domestic affairs. In the broader sense, a state’s strength is decided by how it may successfully have penetrated the society and mobilized internal resources (Clark, 1999: 56-58; Migdal, 1988: 4). Of course, both aspects of state power are reinforced by the legitimacy endowed to the government (Clark, 1999: 59-60). Taiwan, as former colony of Japan, was handed over to the Republic of China after World War II. Having been defeated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the civil war, the KMT Kuomintang (KMT, or Chinese Nationalist Party) under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek took refuge in Taiwan in 1949, and had ever since maintained one of the longest bureaucratic-authoritarian regimes in the world on this island. Having being shored up by military measures, the KMT regime was further reinforced by three pillars: warding off military invasion from the People’s Republic of China, providing material incentives from economic development, and encouraging patriotism to the state as the sole legitimate successor of the millennial lineage of Chinese dynasties.[14][14] Penetrating from the fortified power center in Taipei to the peripheries, the ethnicized KMT state had maintained both horizontal and vertical divisions of labor: while the Mainlander Chinese would occupy the state apparatus, the native Taiwanese would have no choice but to stay in the private sector; while the former would monopolize political power in the central government, the latter would be indirectly controlled through divide-and-rule among combative local factions purposefully patronized by the KMT. The strong state at this party-state era is best understood as “despotic control,” to borrow the term coined by Clark (1999: 58). Migdal (1988: 35) would designate the strong state-week society combination as “pyramidal.” What broke the four-decade of the KMT party-state impasse was the unexpected succession to the presidency by Lee after Chiang Chin-kuo’s sudden demise in 1988. To avoid breakdown in the global third wave of democratization, Lee embarked on political liberalization and democratization in a piecemeal fashion, whence the authoritarian regime began to crumble. While busy consolidating his power by disarming the conservatives within his own party, Lee sought to naturalize the regime incrementally by collaborating with the then opposition DPP (Democratic Progressive Party) in a series of constitutional amendments. Also, by promoting native elites to the ruling echelon, Lee turned the KMT into a lateral seceding party,[15][15] and eventually dismantled the KMT into four political parties. Once the opposition had decided to undertake political reforms from within the system, the main arena for power transition had been national elections. The elections for the National Assembly and the Legislative Yuan were normalized sequentially in 1991 and 1992. It was the native Lee Teng-hui of the KMT who became the first directly elected President in 1996, although the dissent native Chen Shui-bian of the current ruling DPP did win the second presidential election in 2000 largely as a result of the internal feud and split of the KMT. In

recollection, the state remained strong during this period of liberalization

and democratic transition, as corporatist authoritarianism was largely

intact, giving that fact that the state had maintained extensive control over

mobilizing resources. The society

had remained weak after the onslaughts by the alien-regime in the 1950s. What had compensated for declining

state’s authority was

newly gained legitimacy resulting from the process of democratization.[16][16] Tentative

Conclusions

The adjustments of

agricultural policy under the framework are best understood as a

constructivist effort made by the state of Taiwan to engage with the

international society. Here,

globalization is thus perceived as an opportunity to transform the

state. In the past, the state was

strong in terms of its coercive control. Gradually, the state power has

been enhanced in the process of democratization. Consequently, the state has

enjoyed autonomy in facing international challenges. Nevertheless, the strong state has also been conceived under the condition that the society remains weak. As Taiwan is struggling for democratic consolidation, ethnic groups, kinships, regional clans, and local factions are resisting state control and infiltrating the state apparatus. If a weak state is accompanies by an intransigently weak society, we may witness an anarchical configuration as termed by Migdal (1988: 35). It is doubtful whether the Taiwan state may continue enjoying such a liberal agricultural stance. References Barnett,

Michael. 1999. “Culture,

Strategy and Foreign Policy Change: Israel’s

Road to Oslo.” European Journal of International

Relations, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 5-36. Booth,

Ken, and Steve Smith, eds.

1995. International Relations

Theory Today. Oxford: Polity

Press. Breuning, Marijke, and John T. Ishiyama. 1996. “The Dialogue between International Relations and Comparative Politics: A Response to Zahariadis.” International Studies Notes, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 15-23. Caporaso, James A. 1997. “Across the Great Divide: Integrating Comparative and International Politics.” International Studies Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 4, pp. 563-91. Checkel, Jeffrey T. 1998. “The Constructivist Turn in International Relations Theory.” World Politics, Vol. 50, pp. 324-48. Clark, Ian. 1999. Globalization and International Theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Coleman, William D., and Christine Chiasson.

2000. “State

Power, Transformative Capacity and Resisting Globalization: A Analysis of

French Agircultural Policy, 1960-2000.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting

of the Council for European Studies, Chicago, March. Copeland, Dale C. 2000. “The Constructivist Challenge to Structural Realism: A Review Essay.” International Security, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 187-212. Di Palma, Giuseppe. 1990. To Craft Democracy: An Essay on Democratic Transitions. Berkeley: University of California Press. Diamond, Larry. 1994. “Toward Democratic Consolidation.” Journal of Democracy, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 4-17. Hopf, Ted. 1998. “The Promise of Constructivism in International Relations Theory.” International Security, Vol. 23, No. 1 (EBSCOhost Full Display). Huang, Xiaoming. 1999. “Contested State and Competitive State: Managing the Economy in a Democratic Taiwan.” Paper presented at the 40th Annual Convention of the International Studies Association, Washington, D.C., February, 10-20. Jackson, Robert, and Georg Sørensen. 1999. Introduction to International Relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Jackson, Robert H. 1990. Quasi-states: Sovereignty,

International Relations and the Third World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Katzenstein,

Peter J., and Nobuo Okawara. 2002/02. “Japan, Asian-pacific

Security, and the Case for Analytic Eclecticism.” International Security, Vol.

26, No. 3, pp. 153-85. Lin,

Chien-pin.

1998. “Domestic

Bargaining in Taiwan’s International Agricultural

Negotiations.” Asian Survey, Vol. 38, No. 6

(Expanded Academic ASAP). LIN,

Kuo-Ching(林國慶), and WU, Peing-Ing(吳珮瑛).

2000. 台灣加入WTO農業補貼制度調整之分析

(Analysis of the Adjustment of Agricultural Subsidy Policy in Taiwan for

Entering the WTO). 台灣土地金融季刊,

Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 1-26 Mayer,

Frederick W. n.d. Interpreting NAFTA: The Science and

Art of Political Analysis.

http://www.ciaonet.org/book/mayer/mayer02.html. Migdal,

Joel S. 2001. State in Society: Studying How

States and Societies Transform and Constitute One Another. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Migdal,

Joel S. 1988. Strong Societies and Weak State:

State-Society Relations and State Capabilities in the Third World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University

Press. Milner,

Helen V., and Robert O. Keohane. 1996. “Internationalization

and Domestic Politics: An Introduction,” in

Robert O. Keohane, and Helen V. Milner, eds. Internationalization

and Domestic Politics, pp. 3-24.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Moravcsik,

Andrew. 1993. “Introduction:

Integrating International and Domestic Theories of International Bargaining,” in

Peter B. Evans, Harold K. Jacobson, and Robert D. Putnam, eds. Double-Edged

Diplomacy: International Bargaining and Domestic Politics, pp. 1-42. Berkeley: University of California

Press. Nordlinger,

Eric A. 1981. On the Autonomy of the Democratic

State. Cambridge, Mass.:

Harvard University Press. Putnam,

Robert D. 1988. “Diplomacy and

Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games.” International Organization,

Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 427-60. Rosecrance, Richard. 1996. “The Rise of

Virtual State.”

Foreign Affairs, Vol. 75, No. 4, pp. 45-61. Rosenau,

James N. 1997. Along the Domestic-Foreign

Frontier: Exploring Governance in a Turbulent World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Shih,

Cheng-Feng.

1994. “An

Attempt at Understanding Taiwan’s Economic

Development.” Journal of Law and Political

Science, No. 2, pp. 59-82. Shih,

Cheng-Feng.

1993. “Strong

State as an Explanatory Variable of Economic Development: With a Focus on the

Case of Taiwan.”

Journal of Law and Political Science, No. 1, pp. 133-47. Strange,

Susan. 1996. The Retreat of the State: The

Diffusion of Power in the World Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Waltz,

Kenneth N. 1979. Theory of International Politics. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. Waltz,

Kenneth N. 1959. Man, the State, and War. New York: Columbia University Press. Wendt,

Alexander E. 1987. “The

Agent-Structure Problems in International Relations Theory.” International Organization,

Vol. 41, No. 3, pp. 335-70. WU,

Peing-Ing(吳珮瑛), and LIN, kuo-Ching(林國慶).

2000. 農業補貼制度之調整與穩定農家所得之研究

(Agricultural Subsidies and Farmers’

Income). Department of

Agricultural Economics, National Taiwan University. Zahariadis, Nikolaos. 1995. “Toward a More Meaningful Dialogue between International Relations and Comparative Politics.” International Studies Notes, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 23-28. |