|

American Military Posture in East

Asia: With a Special Focus on Taiwan* |

||

Cheng-Feng Shih, Associate Professor

Department of Public Administration, Tamkang

University, Tamsui, TAIWAN We will build our defenses

beyond challenge, lest weakness invite challenge. We will meet aggression and bad

faith with resolve and strength. George W. Bush (2001/1/20) Introduction

In this study, we attempt to understand American military posture in East

Asia within the context of a US-Japan-China-South Korea-Taiwan pyramid, where

the US plays the role of benign leader at the apex. With the demise of the Soviet Union,

China has become the only power to challenge not only regionally bust also

globally. Equipped with a realist

predisposition, the Bush administration appears apt to keep a watchful eye on

the emerging competitor China, who has alarmed both the US and her allay

Japan during the 1995-96 missile crises against Taiwan. With this strategic understanding in

mind, we will seek to allure to some military arrangements contemplated by

the US. Efforts will be made to

examine five official documents already made to the public since President

George W. Bush’s inauguration, including his own the National Security

Strategy of the United States of America, and the Department of Defense’s

Quadrennial Defense Review Report, Nuclear Posture Review, Annual

Report to the President and the Congress, and Annual Report on the

Military Power of the Peoples’ Republic of China. Before our conclusions, we

recapitulate the US policy toward Taiwan within our broad framework. Strategic

Predispositions

In the traditional literature of International Relations, two

epistemologically rationalistic paradigms have been competing with one

another for domination: while Realism/Neo-Realism would emphasize the

rationale of national interests, security, and power, and thus stress

balance-of-power in international anarchy, Idealism/ Liberalism would focus

on the importance of international norms, institutions, and cooperation. It is therefore tempting to grossly

interpret American foreign policy behavior under Republican and Democrat

presidents into realist and liberal ones respectively. However, in their policy application,

these two ideal types are practically inadequate in the sense that there is

no straightforward isomorphic division between Republican and Democrat

administrations along the spectrum of strategic predisposition. Particularly, the analytic distinction

between containment and engagement may fade into vagueness as the presidents

may find themselves inescapably entrapped to adopt a nonpartisan posture

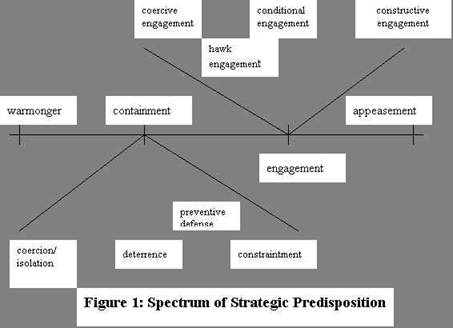

(Figure 1). For

instance, while the Democrat Clinton would feel more attuned to all sorts of

strategies under the umbrella of engagement, from constructive engagement to

coercive engagement, the Republic Bush may entertain a continuum of

containment in all clothes, from coercion/isolation to constraintment,

to borrow the term from Segal (2000).

It is therefore not surprising to discover that general external

orientations of both Democrat and Republic would at times converge when the

sets of engagement and containment intersect with each other, culminating

into the seemingly oxymoron of hawk engagement/preventive defense identified

by Cha (2002). In

practice, it was the Democrat Clinton who had sent two carriers to the Taiwan

Straits during the 1995-96 missile crises, which would be considered

disharmonious, if not antithetical, to his own operational code or belief

system. Similarly, we would not

be surprised if the Republican Bush should venture out of the deterrence/defense

baseline and thus choose to adopt a constraintment

gesture, let us say, in order to fortify homeland security, especially in the

aftermath of the September 11 at home. Facing

this analytic flux and related theoretic/paradigmatic deficiency that favors

parsimonious explanations, Katzenstein and Okawara (2001) recommend an “eclectic” Realist-Liberal

perspective that would explain seemingly disparate, if not contradictory, US

strategies on different issues toward Japan, that is

military alliance and economic competition.[1][1]

Nonetheless, their perspective fails to specify the conditions when a

state actor like the US would take a unified or eclectic approach. Instead, we would argue that a more

fruitful complement to the Realist/Liberal dichotomy is to go beyond the

positivist epistemology and embrace an emerging reflective Constructive lens

underscoring that ideas and values decide national

identities and interest, which in turn determine state behavior (Copeland,

2000). Taiwan Japan China Korea alliance  Figure2:

Pyramid Relationships in East Asia

In this study, we perceive the US as a lone superpower resolute to uphold a

capitalistic and democratic world order in the Post-Cold War era. Facing potential challenge from China

both globally and regionally, the US seems steadfastly determined to retain

its hegemonic status, especially in East Asia, rather than to share the

condominium with China and Japan, or to retreat from the Asian-Pacific region

and become merely a balancer.[2][2]

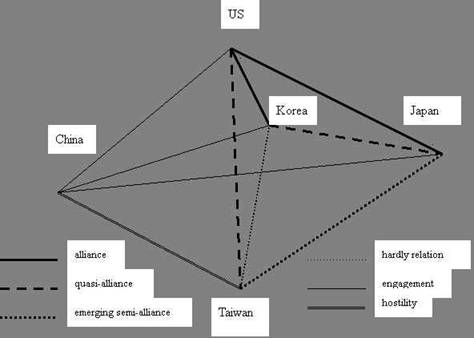

With this self-identity in mind, US foreign policy and strategic considerations

would be juxtaposed against a pyramid (Figure 2) in East Asia, where Japan,

Korea, and Taiwan are enlisted to form, in a minimum, a defense shield,

or/and, to the maximum, an offensive bow against China although both

engagement and containment disguises may be alternatively employed.

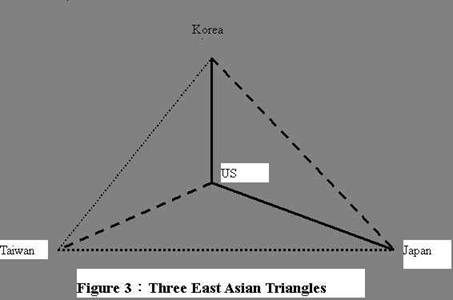

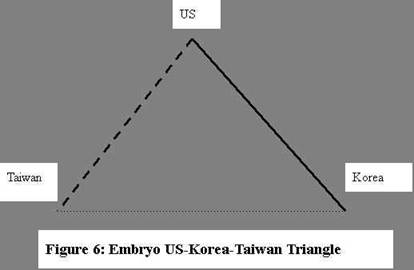

Embedded in this US-Japan-Korea-Taiwan strategic landscape are three

interlocked triangular relationships composed of bilateral alliances,

quasi-alliances, and some emerging semi-alliance,[3][3] which mount to

a US-centered quasi-multilateral security community is East Asia (Figure

3). So far, the US, Japan, Korea,

and even Taiwan[4][4] have disseminated symbolical and

substantive elements of engagement to placate China. Nonetheless, if China is

determined to transform itself from a land power to a maritime power,[5][5] efforts will be made to penetrate these

strategic protective arrangements.

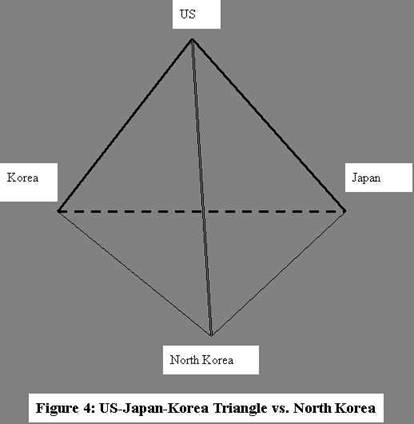

Among the three triangles, the US-Japan-Korea one is most robust (Figure

4). While the US has forge

military alliance with Japan and South Korea (Korea, or Republic of Korea) in

1951 and 1953 respectively, the relationship between Japan and Korea have

been reinforced not only by their common threats from North Korea, but also

from their dependence on US military commitment. In what Cha’s

(2000) characterization as a “quasi-alliance,” Japan and Korea would eschew

their historical animosity and thus to enhance their relationship if their

mutual perception of US determination is declining. This triangle would not be so solid in

case when the two Koreas are unified and decide to collaborate with China to

deter Japan’s ascendance.

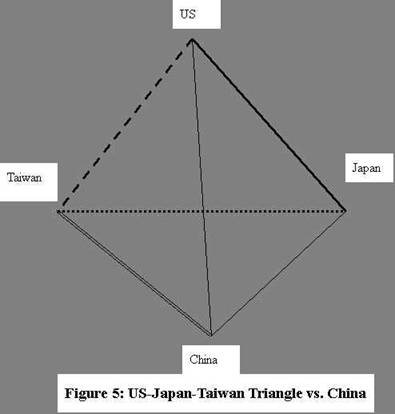

On

the other hand, Japan has consistently stood aloof to Taiwan even though they

shared colonial relations, though asymmetric, for half a century before the

end of the war. The Native

Taiwanese, some of whom still wholeheartedly harbor their romantic

reminiscence of the good old days before the war,[6][6] must have been distressed, if not

humiliated, by Japanese selective amnesia and blindness. Moreover, some Mainlander Taiwanese,

who themselves or whose immediate forebears were forced to take refugee in Taiwan after the Chinese Nationalists

(Kuomintang, KMT) were defeated by the Communist Chinese (CCP) in 1949, would

not shy away from their anti-Japanese sentiments lingering from the war

memory.[7][7]

Any substantive improvement between Japan and Taiwan must rest on how

they would reconcile their past.

On the part of Taiwan, particularly, domestic politics in the form of

ethnic competition needs to be de-linked with foreign policy making. Nonetheless,

after the 1995-96 missile crises in Taiwan Straits, both the US and Japan

seemed to have finally realized that they no longer could afford tolerating a

loophole in their defensive network against Chinese expansion eastwards. The revised Guidelines for Japan-US

Defense Cooperation[8][8] promulgated in 1997 was

perceived for military consolidation in order to maintain acceptable

balance-of-power in East Asia, if no to contain China. Within this new configuration, Taiwan

may probe the possibility to make great strides in forging some linkage with

Japan in the form of quasi-alliance based on hitherto solid military alliance

between the US and Japan. Of

course, an emerging Japan-Taiwan collective defense bund, thus, may also help

to upgrade current U.S. security commitment to Taiwan. However, affirmative US warrant is

predicated on the condition that Taiwan is averse to political integration

with China in any format, which has been jeopardized by Taiwan’s recent

single-minded overtures to court, if not to hedge, China.

The weakest component in the US strategic contemplation in led East Asia is

the missing US-Korea-Taiwan triangle (Figure 6). So far, there is hardly any diplomatic

relation between South Korea and Taiwan, not to mention military one.[9][9]

Animosity between them is evidenced in lack of flag-carrying airlines

between the two capitals since they broke off their formal relations in

1992. Sporadic competitions even

between their own civilians would cause displeasure, at least on the

Taiwanese part. Historical

memory, if not racist chauvinism, must have played a crucial role in this

thorny relation.[10][10]

Still, if Taiwan is ready to stage rapprochement with China, it

would be absurd to reject Korea.

After all, Korea was one of the last “powers” that yielded to China’s Hallstein Doctrine, persistent

demands for Korea’s apology would render Taiwan’s security and national

interests secondary to other considerations. New American

Military Posture

Hierarchically, military strategy is based on the guideline laid down in

defense strategy, which in turn are derived from national security

strategy. Although it is perhaps

premature to generalize how personal idiosyncratic characteristics have

determine President Bush’s foreign policy orientations,[11][11] he did reveal some Realist propensity

by declaring that the US “will meet aggression and bad faith with resolve and

strength” in his inaugural address (Bush, 2001). He also exhibits similar Realist

mind-set in his National Security Strategy of the United States of America

by calling attention to “unparalleled” US military strength and economic

influence, and reiterating US intention to create a “balance of power” that

favors human freedom (Bush, 2002; 2001).

While directing three grandiose goals of freedom, peace, and human

dignity, he unfolds eight international strategies: to champing aspirations

for human dignity, strengthen alliances to defeat global terrorism, defuse

regional conflicts, prevent enemies with weapons of mass destruction (WMD) to

threaten the US, ignite global economic growth, expand development, develop

cooperation, and transform US national security institutions. It appears that he does not disguise

his intention to defeat enemies (p. 30) while judging deterrence ineffective

against enemies (p. 15).

Although Bush refers to terrorism as enemy and rogue states and terrorists as

challenges (2002: 5, 13), China is particularly identified as one that is

threatening its neighbors in the Asia-Pacific region. He accordingly contends to seek a

“constructive relationship” with China (p. 27). He goes on to remind China that the US

is committed to the defense of Taiwan, which he attributes as “friend” (p.

3), under the Taiwan Relations Act.

The Quadrennial Defense Review Report submitted by the Department of

Defense (2001) puts forward four defense policy goals under new security

environment[12][12]: to assure allies and friends,

dissuade adversaries, deter aggression and coercion, and defeat any adversary

if deterrence fails (pp. iii-iv, 11-13).

More concretely, seven strategic tenets are identified: to manage

risks, adopt a “capabilities-based” approach to defense,[13][13] defend the US and project military

power, strengthen alliances and partnerships, maintain favorable regional

balances, develop broad military capabilities, and transform defense (pp.

13-16). Accordingly, force

planning will be drawn to defend the US, deter aggression and coercion,

defeat aggression, and conduct small-scale contingency operations (pp.

17-21).

The QDR further identifies three broad categories of US national

interest: to ensure US security and freedom of action, honor international

commitments, and contribute to economic well-being (p. 2). While Northeast Asia, and East Asian

littoral are identified among other areas as critical one that the US would

preclude “hostile domination” (p. 2), the East Asian littoral is perceived as

a “particularly challenging area” (p. 4). Although not explicitly identified,

Taiwan is unmistakably located in this Asian theater stretching from the Bay

of Bengal to the Sea of Japan.

A more detailed strategic posture designed for the 21ist century is partially

unveiled in excerpts of the heatedly debated Nuclear Posture Review

submitted to the Congress by the Department of Defense (2002a).[14][14]

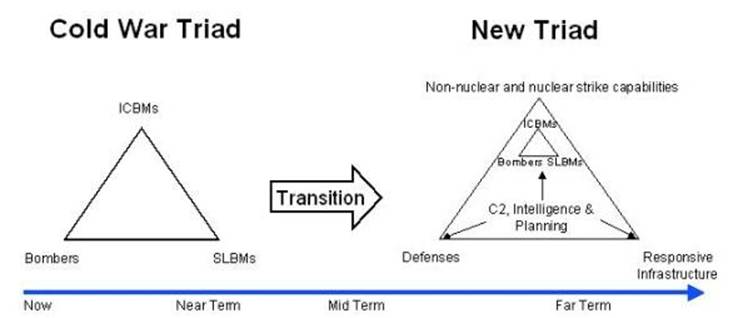

Under the new strategic triad (Figure 7), while traditional ICBMs,

Bombers, and SLBMs are reserved under one pillar, new impetus is given to

active and passive defenses, and revitalized defense infrastructure, with

enhanced command, control, and intelligence biding the three pillars. While non-nuclear offensive forces,

meaning conventional strike and information operation, are enlisted to

complement nuclear ones, missile defense capabilities are formally employed

to assured security partners, dissuade adversaries, deter aggression, and

defeat small-scaled missile attacks as dictated in the QDR.[15][15]

source:

http://www.defenselink.mil/news/Jan2002/g020109-D-6570C.html

Figure7: News Strategic Triad

Interesting enough, the Department of Defense chose not to conceal the part

on China along with six other states to use nuclear weapons[16][16] in the NPR excerpts, including

Russia, Libya, Syria, Iran, Iraq, and North Korea: Due to the combination of

China’s still developing strategic objectives and its ongoing modernization

of its nuclear and non-nuclear forces, China is a country that could be

involved in an immediate or potential contingency.

Indirectly associated is the recognition that Taiwan is on one of the

“immediate contingencies”[17][17] when a military confrontation may take

place over its legal status contested by China, and for which the US pledges

to prepare its nuclear forces for preemptive strikes.[18][18]

Even though the QDR was released after the September 11, the US

security strategy specified largely stayed the old course as the aged-old

“two theaters” of operation remained intact, if not scantly mentioned (p.

21). Full-fledged development of

a new defense approach did not appear until the Department of Defense (2002b)

submitted its Annual Report to the President and the Congress,

including phasing out two major theater war construct, reorganizing and

revitalizing the missile defense research, reorganizing space capabilities,

enhancing homeland defense and accelerating transformation, adopting a new

approach to strategic deterrence (New Triad), and adopting a new approach to

balancing risks.[19][19] Apparently, this report is more

attuned to the NPR than the QDR.

In this report, the Asian littoral is again listed as one of critical areas

that the US is committed to prevent hostile domination. Although having not picked out China, the

report discerns that some rising and declining regional powers which are

developing or acquiring nuclear, biological, or chemical (NBC) capabilities

to threaten stability in regions critical to US interests. Under the heading of Asia, it

relentlessly states: Maintaining a stable

balance in Asia will be both a critical and formidable task. The possibility exists that a military

competitor with a substantial resource base will emerge in the region. The Asian littoral represents a

particular challenging area for operations. The distances are vast and the density

of U.S. basing and en route infrastructure is lower than other critical

regions. This place a premium on

secure additional access and infrastructure agreements and on developing

systems capable of sustained operations at long distances with minimal

theater-based support.

In summer 2002, the Department of Defense (2002c) submitted its Annual

Report on the Military Power of the Peoples’ Republic of China to the

Congress, alerting China’s ballistic missile modernization, which would

upgrade its nuclear deterrence and operational capabilities for contingencies

in East Asia. The report is

keenly watchful that:[20][20] Preparing for a potential

conflict in the Taiwan Strait is the primary driver for China’s military

modernization. Beijing is

pursuing the ability to force Taiwan to negotiate on Beijing’s terms

regarding unification with the mainland.

It also seeks to deter, deny, or complicate the ability of foreign

forces to intervene on Taiwan’s behalf. (p. 11) In the

section on security situation in the Taiwan Strait, it is observed that: Both Beijing and Taipei have stated that they seek

a peaceful resolution to the unification issue. However, the PRC’s ambitious military

modernization casts a cloud over its declared preference for resolving

differences with Taiwan through peaceful means. Beijing has refused to renounce the

use of force against Taiwan and has listed several circumstances under which

it would take up arms against the island. . . . Beijing’s primary political

objective in any Taiwan-related crisis, however, likely would be to compel

Taiwan authorities to enter into negotiations on Beijing’s terms and to

undertake operations with enough rapidity to precluded third-party

intervention. (p. 46) The DoD also shows its grave concern in the report that

China’s 300 modernized conventional SRBMs would pose as an effective

conventional strike force against Okinawa when forwardly deployed, or against

Taiwan[21][21] when deployed further inland (pp. 2,

25, 50-51), fretting that “Taiwan’s ability to defend against ballistic

missiles is negligible.” (p. 51)[22][22]

Most ominous is the frightful account that: The PLA’s offensive

capabilities improve as each year passes, providing Beijing with an

increasing number of credible options to intimate or actually attack Taiwan.

. . . The PLA also could adopt a decapitation strategy, seeking to neutralize

Taiwan’s political and military leadership on the assumption that their

successors would adopt policies more favorable to Beijing. (p. 47) No

less alarming is the prospect that three scenarios of coercive options have

been contemplated by China: information operations, air and missile

campaigns, and naval blockades.

If coercion fails, outright Chinese invasion is expected to follow (p.

48). The US-China Security Review

Commission (2002) even envisages that once missile attacks are launched,

China would continue the strike until Taiwan surrenders.

The Department of Defense (2002c) appears worrisome that China’s secure

control over Taiwan would eventually “allow the PRC to move its defensive

perimeter further seaward.” (p. 10)

The DoD plainly realizes that China’s

military modernization is not only planned against Taiwan, but also at

incurring the US risks in case of Taiwan contingency in the future (p

50). To be sure, the DoD is adamant that whether China would succeed in its

military campaigns is largely decided by how Taiwan may receive firm support

from the US.

Reflecting the basic tenet of the Taiwan Relations Act, the Department

of Defense (2000) has already pledged that: It is the policy of the United States to consider

any effort to determinate the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means,

including boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the

Western pacific area and of great concern to the United States; to provide

Taiwan with arms of a defensive character; and to maintain the capacity of

the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion

that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the

people of Taiwan. The Department of Defense

(2000) has affirmed: The United States takes

its obligation to assist Taiwan in maintaining a self-defense capacity very

seriously. This is not only

because it is mandated by U.S. law in the TRA, but also because it is our own

national interest.

Therefore, the US military commitment to Taiwan is determined by how the

former would conceive of itself in terms of the existence of the latter. Evolving American

Policy toward Taiwan Since the conclusion of World War II in 1945, the

US has witnessed eleven administrations, from Truman to Bush, and its

relationship with Taiwan/Republic of China (ROC) has undergone fluctuating

alternation. The honeymoon

between the two countries from the wartime alliance plumped to the lowest

point in 1949 when the Truman administration adopted its hand-off policy

toward the Chinese civil war and waited to see the annexation of Taiwan by

the Communist Chinese. The US

policy was unexpectedly reversed after the Korean War broke out in 1950, when

the Seventh Fleet was dispatched to protect Taiwan. The US-Taiwan relations turned into a military

alliance and thus reached its peak when a Mutual Defense Treaty was

signed in 1954. By and large, the

Kennedy and Johnson administrations retained closer relations with Taiwan,

especially during the heydays of the Vietnam War. However, once the Nixon and Ford

administrations were resolved to court China in faithful pursuit of

Kissinger’s grand strategy of fighting an

one-and-half war against the Soviet Union, Taiwan was gradually

abandoned. The amiable

relationship came to another slump in 1979 when the Carter administration

decided to derecognize the ROC and established foreign relation with the PRC.

Regardless, a Taiwan Relations Act was

promulgated in the same year, which stands as the watershed of American

policy toward Taiwan. Before the TRA,

Taiwan had long been treated as but one component of the US global strategic

thinking to counter China.

Thereafter, the US has been more inclined to look at its separate

relations with Taiwan detached from China although the US considerations in

these days have to be constrained by Chinese claim of Taiwan’s territory in

their mutual pursuit of accommodation. So far, the most important indicator of the

evolution of the US policy toward Taiwan has been its contemplation of the

legal status of Taiwan. Until

1950 the US had persistently taken the position that Taiwan was part of

China. To justify its protection

of Taiwan after the outbreak of the Korean War, the Truman administration

declared that the legal status of Taiwan was uncertain and should be settled

internationally. The policy

lasted until 1972, when the U.S. formally acknowledged in the Shanghai Communiqué[23][23] that “all Chinese on either side of

the Taiwan Strait maintain that there is only but China and Taiwan is a part

of China.” In the 1979 Joint

Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between the United

States and the People Republic of China,[24][24] the US “acknowledge the Chinese position that there is but one China and

Taiwan is part of China.”

Similarly in the 1982 U.S.-China Joint Communiqué (or 817

Communiqué),[25][25] it is reiterated that the US “acknowledged the Chinese position

that there is but one China and Taiwan is part of China.” (emphases added) While the so-called “One China Policy” has been

embodied in the “Three Communiqués” between the PRC and the US, of which the

contents may have varied and been subject to different interpretations over

the years with changing contexts, it is categorically different from the “One

China Principle” espoused by China.

Rationally speaking, one China carries a host of connotations along

the spectrum from One China=PRC (Taiwan

incorporated), One China=Two Governments (CCP

& KMT/DPP), One China=ROC, One China=Historical, Cultural,

Geographical China, and One China=One

China+One Taiwan. Still, it must be pointed out that the

TRA has nothing like “Taiwan is a part of China.” Since not all interpretations are

contradictory, the US has long chosen to keep all options open to be decided

by Taiwan and China themselves.”

Since “One China Policy” does not necessarily negate the possibility

of recognizing a Republic of Taiwan, this purposeful ambiguity has left an

ample space for proponents of the Taiwan Independence Movement in their

pursuit of establishing an independent Republic of Taiwan. The other manifestation has been American

commitment to Taiwan’s defense as stipulated in the TRA. Although the administrations since

Carter have calculated to be vague over whether the US would send troops to

defend Taiwan in case of war, peaceful resolutions between the Taiwan Strait

have so far been faithful followed.

As the US has designated in the TRA that the security issue of

Taiwan is beyond any challenge, it has been unconditionally invoked to

demonstrate the US commitment to defend Taiwan, suggesting its primacy over

the 817 Communiqué, which was vividly demonstrated in the 1995-96

Missile Crises, when Clinton sent USS Nimitz and USS Independence to deter

China, testifying again that the security of Taiwan as guaranteed in the TRA

outweighs other policy considerations. In the main, the Clinton administration adopted a

strategy of “Comprehensive Engagement” with China in the post-Cold War

era. A

devastating punch come from the “Three No’s” during Clinton’s visit in

China in 1998.[26][26] On the other hand, President George W.

Bush no longer considers China as a “constructive strategic partner,”[27][27] but rather a competitor in a global

strategic design focused on the Asian-Pacific region. So far, while President Bush has shown

his reluctance to mention the three, now out of date, Communiqués, he has

also recurrently demonstrated his goodwill toward Taiwan. For instance, he openly pledged

to do “whatever it took to help Taiwan defend herself” in case China attack

Taiwan,[28][28] promised to help Taiwan joining the

World Health Organization (WHO), and even referred to Taiwan as “Republic of

Taiwan.”[29][29] Before he embarked on his trip to East

Asia in April 2002, he called attention to Taiwan as “good friend” along with

Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, and the Philippines.[30][30]

While speaking to the Japanese Diet, he reiterated American

“commitments to the people on Taiwan.”[31][31]

At a press conference in Beijing, he brought up the Taiwan

Relations Act in front of Chinese President Jiang Zemin[32][32]; again, he wasted no time reminding

the Chinese audience of the US “commitment to Taiwan” and avouching American

determination to “help Taiwan defend herself if provoked” by invoking the Taiwan

Relations Act while delivering a speech in Tsinghua University, Beijing.[33][33]

In return for Chinese clamor for “peaceful unification,” he retorted

with such expressions as “peaceful settlement” and “peaceful settlement.” Although Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz

was recently forced to answer that the US does “not support independence for

Taiwan” while challenged by a compound question uttered by a journalist from

Taiwan,[34][34] he was said to have expressed his

regret for any inconvenience incurred to the Taiwanese. Regarding the standard responses in

the form of “being opposed to” or “not to support” Taiwan independence, we

may come with two rational interpretations. For one thing, while the US would not

allow China to swallow Taiwan because of American interest, it leaves up to

the Taiwanese to decide whether they would get rid of the iron cage under the

Republic of China. Furthermore,

it is beneficial to the Taiwanese if the US openly unveil her intention not

to involve herself on the issue of Taiwan independence as the Chinese would

not have any opportunity to accuse the US meddle in Taiwanese exercising

their right to self-determination. Conclusions In retrospection, the relationships between the US

and Taiwan in the past two decades had been amount to a quasi-alliance in

short of the status of free association.

What has been left out is the determination of the Taiwanese to seek

an independent Republic of Taiwan.

As a setter’s state, the US share with Taiwan’s passion to breakaway from the chains imposed it by the former land

of origin since the norm of self-determination is the highest form of human

rights. The Taiwanese have the

same right to decide their destiny as the Americans did according to the

principle of people’s sovereignty.

As the nation-state is still the standard bearer of people even in the

post-Cold War ear, Taiwan, in its legitimate quest

for a de jure independent

statehood, deserve its fair share in the international arena and ought not to

be deemed as a reckless troublemaker. Nevertheless, the people of Taiwan need to reach a

consensus on Taiwan’s future even though they may retain dissimilar, but not

necessarily contradictory, outlook of national identity. The ruling elite, not the US, is to be

blamed for Taiwan’s isolation because of their partisan manipulations of this

issue. Eventually, the bottom

line is whether the Taiwanese do request a nation-state of their own choice,

not any state imposed. The real

issue we are facing is Chinese irredentism to incorporate Taiwan, not

Taiwanese secession from China.

After all, the current Chinese government has never reigned on

Taiwan. Nonetheless, as along as

the Taiwanese consider themselves as ethnic Chinese in primordial

conceptions, racially or/and culturally, they are mentally destined to

imprison themselves in Chinese political penitentiary and economic

abyss. The ultimate trial for the

Taiwanese would be the following: if China becomes politically democratic and

economically developed, how many Taiwanese would choose to get unified with

China? How many people would

reply definitively negative? Bush, George W. 2002. The National Security Strategy of

the United States of America.

http://www.comw.org/qdr/offdocs.html. Bush, George W. 2001. “Bush Inaugural Address.” http://www.cnn.com/ ALLPOLITCS/inauguration/2001/transcripts/template.html. Cha, Victor D. 2002. “Hawk Engagement and Preventive

Defense on the Korean Peninsula.”

International Security, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 40-78. Cha, Victor D. 2000. “Abandonment, Entrapment, and

Neoclassical Realism in Asia: The United States, Japan, and Korea.” International Studies Quarterly,

Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 261-91. Christensen, Thomas J. 2001. “Posing Problems without Catching Up:

China’s Rise and Challenges for U.S. Security Policy.” International Security, Vol.

25, No. 4, pp. 5-40. Christensen, Thomas J. 1999. “China, the U.S.-Japan Alliance, and

the Security Dilemma in East Asia.”

International Security, Vol. 23, No. 4 (EBSCOhost). Copeland, Dale C. 2000. “The Constructivist Challenge to

Structural Realism: A Review Essay.”

International Security, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 187-212. Crouch, J. D. 2002. “Special Briefing on the Nuclear

Posture Review.” http:// defenselink.mil.news/Jan2002/t01092002_t0109npr.html. Department of Defense. 2002a. Nuclear Posture

Review [Excerpts]. http://www. globalsecurity.or/wmd/library/policy/dod/npr.htm. Department of Defense. 2002b. Annual Report to the

President and the Congress. http://www.defenselink.mil/execsec/adr2002/toc2002.htm. Department of Defense. 2002c. Annual Report on the

Military Power of the People’s Republic of China. http://www.defenselink.mil/news/Jul2002/

d20020712china.pdf. Department of Defense. 2001. Quadrennial Defense Review Report. http://www. comw.org/qdr/offdocs.html. Department of Defense. 2000. December 2000 Pentagon Report on

Implementation of Taiwan Relations Act. http://usinfo.gov/regional/ea/taiwan.

htm. Katzenstein, Peter J., and

Nobuo Okawara.

2002/02. “Japan,

Asian-pacific Security, and the Case for Analytic Eclecticism.” International Security, Vol.

26, No. 3, pp. 153-85. Khalizad, Zalmay, David Orletsky,

Jonathan Pollack, Kevin Pollpeter, Angel Rabasa, David Shlapak, Abram Shulsky, and Ashley Tellis. 2001. The United States and Asia: Toward

a New U.S. Strategy and Force Posture. Rand. http://www.rand.org/publications/MR/MR1315/. Landy, Marc K. 2002. “The Bush Presidency after 9/11:

Shifting the Kaleidoscope.” The

Forum, Vol. 1, No. 1. http://www.bepress.com/forum/

vol1/iss1/art4. O’Hanlon, Michael. 2000. “Why China Cannot Conquer

Taiwan.” International

Security, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 51-86. Ross, Robert S. 2000. “The Geography of Peace: East Asia in

the Twenty-first Century,” in Michael E. Brown, et al., eds. The Rise of China, pp.

167-204. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Press. Segal, Gerald. 2000. “East Asia and the ‘Constraintment’ of China,” in Michael E. Brown, et al.,

eds. The Rise of China,

pp. 237-65. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Press. Tucker, Nancy Bernkopf.

2002. “If Taiwan Chooses

Unification, Should the United States Care?” Washington Quarterly, Vol. 25,

No. 3, pp. 15-28. http://www.twq.com/02summer/tucker.htm. U.S.-China Security Review

Commission. 2002. The National Security Implications

of the Economic Relationship between the United States and China. http://www.uscc.gov/anrp02.htm. |