|

The utilitarian view

that languages are merely instruments of communication. But any given language is not only symbolic

of a given language bust also part and parcel of that culture and its

accompanying ethno-cultural identity.

Joshua Fishman[1] (Ó Murchú,

2000: 85-86)

Language is the

nature of human species, and it is not only an important instrument for communication

but also the carrier of identity, both of the individual and of group. Indeed, it is an instrument for

cultural and spiritual development and expression. To constrain language is to constrain

human nature. This means to

diminish humanity, instead of to elevate and celebrate it.

John Packer[2] (2002)

壹、前言

在過去,一般人被灌輸的看法是「語言只不過是一種溝通的工具」,言下之意,沒有必要去計較語言的使用。事實不然,語言能力左右著接近教育、媒體、以及政府資源等公共財的管道,也就是物質取得的保障;此外,語言往往是一個族群負載文化、表達認同的基礎,因此,語言的選擇更是一種基本的權利[3]。問題是,不管是從資源分配、還是認同確認來看,語言的使用不僅取決於政治權力的多寡,還會回過頭來鞏固支配性語言使用者的權力,因此,族群間的競爭往往是為了語言的選擇。

愛爾蘭籍/裔的「歐洲鮮用語言協會」(European Less Used

Languages Bureau) 前會長Helen Ó Murchú (2000: 82) 便直言不諱:「或明或暗,語言一直是政治議題,因為語言明顯地牽涉到權力差別的問題」。當語言被用來區隔為「自己人」 (insider)、以及「旁人」(outsider) 之際,只要有人佔有優勢,就會有人居於相對劣勢,衝突自是難免 (Packer, 2002),也因此,語言的多元不免被視為社會衝突的根源,或者至少是政治鬥爭的工具。

儘管如此,前北愛爾蘭官方「族群關係理事會」(Community Relations

Council, CRC) 的理事長 Mari FitzDuff (2000) 注意到當前國際潮流對於多元語言的看法有重大變動,也就是在超越宿命式的衝突觀、發展到對於差異的起碼接受,進而企盼進行正面的合作。北愛爾蘭在1970、1990年代分別進行和解,最大的差別在於前者著重權力的分配,後者則兼顧語言的公平性、以及對於族群認同的尊重。自從北愛爾蘭、英國、以及愛爾蘭三方在1998年簽署『北愛爾蘭和平協定』(Northern

Ireland Peace Agreement 1998) 以來,除了設立相關的語言振復機構外,「北愛爾蘭人權委員會」更是積極地在草擬中的『人權法案』(Bill

of Rights) 裡頭規劃「語言權條款」[4]。

貳、語言與族群結構

當前北愛爾蘭的人口約一百六十九萬人[5]。最近一次的人口普查在2001年完成,不過資料尚未對外公佈;根據上一次的人口普查(1991年),人口約一百五十八萬人[6]。根據北愛爾蘭人自己的認知,他們的族群結構大致是以天主教徒、以及新教徒[7]作為分歧的界線;因此,即使是無神論者也要區分到底是屬於天主教徒、還是新教徒,可見宗教標籤代表的是族群認同 (Rose, 1976: 13)。目前兩個族群的人口比率分別是45%:51%[8](見表一、二)。

表一:北愛爾蘭歷年的人口

|

年份

|

1951

|

1961

|

1971

|

1981

|

1991

|

|

|

天主教徒

|

471,460

34.4%

|

497,547

34.9%

|

477,919

31.4%

|

414,532

30.0%

|

605,639

38.4%

|

|

|

|

長老教會

|

410,215

|

413,113

|

405,719

|

339,818

|

336,891

|

|

|

愛爾蘭教會

|

353,245

|

344,800

|

334,318

|

281,472

|

279,280

|

|

|

美以美教會

|

66,639

|

71,865

|

71,235

|

58,731

|

59,517

|

|

|

其他新教徒

|

45,334

|

69,299

|

87,938

|

112,822

|

122,448

|

|

|

新教徒總數

|

875,433

63.9%

|

899,077

63.1%

|

898,910

59.2%

|

792,843

53.5%

|

798,136

50.6%

|

|

|

|

未回答

|

24,028

|

28,418

|

142,511

|

274,584

|

114,827

|

|

|

無

|

---

|

---

|

---

|

---

|

59,234

|

|

|

總數

|

1,370,921

|

1,425,042

|

1,519,640

|

1,481,959

|

1,577,836

|

|

|

資料來源:http://www.geocities.com/pdni/demog,html。

表二:北愛爾蘭歷年的人口(調整過)

|

年份

|

1961

|

1971

|

1981

|

1991

|

2001

|

|

天主教徒

|

503,724

|

560,932

|

618,743

|

674,535

|

759,535

|

|

%

|

35.3

|

36.9

|

40.0

|

42.8

|

45.3

|

|

新教徒

|

903,195

|

926,881

|

884,464

|

844,067

|

859,067

|

|

%

|

63.4

|

61.0

|

57.1

|

53.5

|

51.2

|

|

無

|

18,124

|

31,827

|

45,531

|

59,234

|

59,234

|

|

%

|

1.3

|

2.1

|

2.9

|

3.8

|

3.6

|

|

總數

|

1,425,042

|

1,519,640

|

1,548,738

|

1,577,836

|

1,677,836

|

資料來源:http://www.geocities.com/pdni/demog,html。2001年為推算的數字。

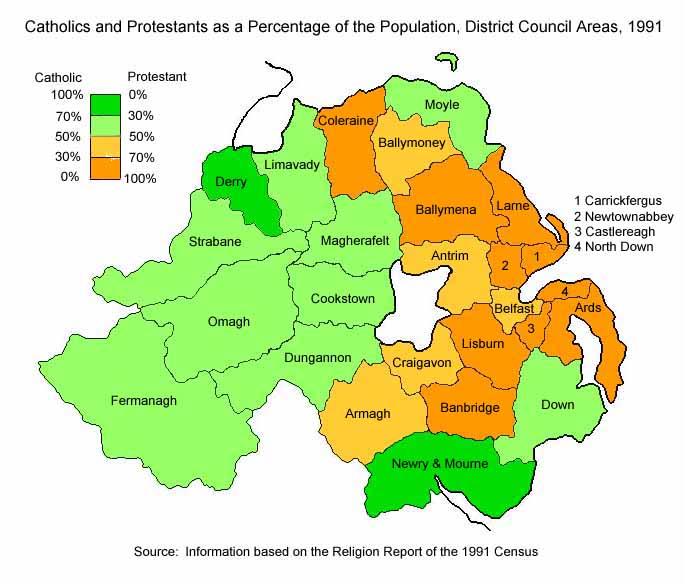

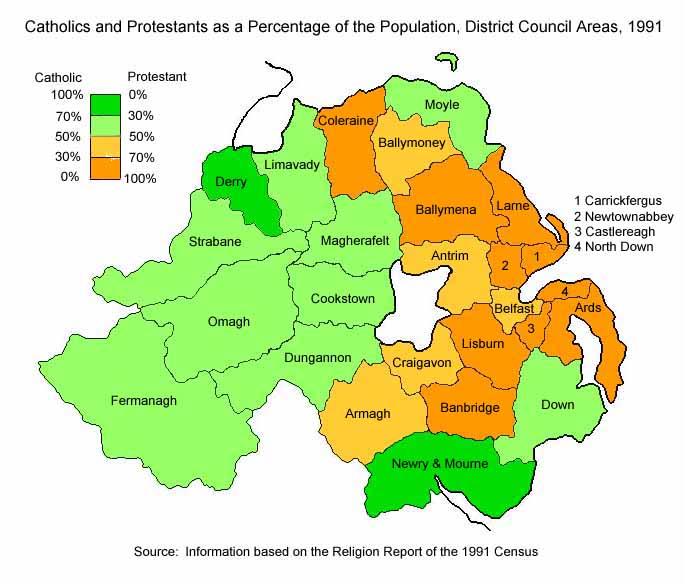

天主教徒主要分布在邊陲的西部,新教徒則以貝爾法斯特為中心的都會區 (Doherty, 1996: 201;見圖一)。

此外,北愛爾蘭還有一些少數族群,分別是華人3,125-5,125人、印度人1,050人、巴基斯坦人641人、Traveller 1,366人、以及其他 88人[9]。其實,宗教信仰在北愛爾蘭又與國家定位、以及國家認同、甚至於社會經濟地位高度相關,也就是相互強化的二分法[10] (Morrow, 1996: 196):

天主教徒=民族主義者=愛爾蘭人

新教徒=聯合主義者=英國人

圖一:北愛爾蘭族群分布

大體而言,天主教徒認為北愛爾蘭的癥結在國家定位,新教徒則認為宗教才是主因,也就是他們對於天主教的排拒;天主教徒的民族認同比新教徒來得清楚,進而反映在他們對於國家定位的看法分歧 (Rose, 1976: 1-14, 10-11)。一般而言,天主教徒大多支持北愛爾蘭應該與愛爾蘭共和國統一,這種政治立場被稱為「【愛爾蘭】民族主義者」(Nationalist),新教徒則多主張留在英國(聯合王國、即United Kingdom),因此稱為「聯合主義者」(Unionist);因此,有些作者會用「民族主義者/天主教徒」(Nationalist

Catholic)、以及「聯合主義者/新教徒」(Unionist

Protestant) 分別稱呼他們[11]。根據『北愛爾蘭和平協定』,每個北愛爾蘭議員選上後必須登錄自己的認同是民族主義者、聯合主義者、還是其他,以便計算法案的通過是否符合「同步共識」(parallel)、還是「特別多數」(special majority)(Strand one-5

& 6)。

天主教徒是愛爾蘭人的後裔,自認為是本地人 (natives),新教徒則是隨著英國征服愛爾蘭而來的墾殖者 (settlers),大多是從1607年就陸續前來的低地蘇格蘭人、或是英格蘭人的後裔;照說,愛爾蘭人與蘇格蘭人有地緣關係、歷史淵源、語言文化相近[12],卻因宗教差異而被以夷制夷(天主教徒vs. 長老會新教徒),終於造成民族認同也南轅北轍,到十九世紀中,兩個族群已經涇渭分明 (Arthur, 1980: 2-3;

Gallagher, n.d.)。既然新教徒都是在北愛爾蘭土生土長,已經很難將他們視為外來者。事實上,一直到1920年為止,新教徒還會自認為「既是愛爾蘭人、也是英國人」,相對地,天主教徒的民族認同則是「是愛爾蘭人、不是英國人」。不過,南北愛爾蘭在1921年分手,新教徒就開始比較不願意承認自己是愛爾蘭人,頂多是「北愛爾蘭人」[13];戰後,他們的「英國人」身分也不太得到英國本土的迴響,兩面不是人,因此,與其說「新教徒」是宗教信仰,不如說是世俗的族群認同、或是政治認同 (Morrow, 1996: 194)。

宗教信仰之所以會成為北愛爾蘭的族群辨識標記,主要是因為愛爾蘭人在被英國人征服後,整個社會崩解、貴族精英潰散,只剩下天主教會還能苟延殘喘,扮演維繫命脈的角色,特別是開辦教會學校。不過,我們必須提醒讀者,北愛爾蘭的族群衝突並不是因為教義差異而導致的宗教衝突,而是北愛爾蘭政府長期由新教徒所控制 (1921-1972[14]),對於天主教徒在政治參與、教育、以及就業上百般歧視,因而強化了原本彼此在國家定位、以及國家認同的歧異。

從都德王朝 (House of Tudor) 的亨利八世君臨愛爾蘭 (1541) 到十九世紀為止[15],愛爾蘭語被當作是當地叛亂份子的所使用的語言,英國費盡心思加以打壓、查禁 (Sutherland, 2000:

7)。一直到1713年為止,愛爾蘭人大致被通盤同化,只剩不識字的鄉下人還會說「方言」。英國於1831年在愛爾蘭設立所謂的「國民學校」(national school),使用英文教學;學校不教愛爾蘭語,學生如果用愛爾蘭語交談,會被老師嘲笑、羞辱、處罰,一直延續到二十世紀初期為止 (Ó Riagáin, 2002)。不過,在十九世紀下半葉,天主教士受到西歐的啟蒙運動、以及日爾曼的浪漫式民族主義 (romantic

nationalism) 影響,相信文化差異是獨立運動的利器,因而開始著手語言的自我保護;然而,對於支配政治的新教徒來說,愛爾蘭語幾乎就是天主教、或是愛爾蘭民族主義的同義字,心生恐懼而加緊壓制,造成兩極化 (Andrews, 2000)。

根據1991年的人口普查,目前北愛爾蘭會說愛爾蘭語的人數只有131,974,約8.8%,特別是在南區、以及西區,不過,人數最多的還是在貝爾法斯特,有27,430人,其次是在第二大都會區Derry,有9,731人;在一些「地方政府區域」(Local Government District,

LGD),會講愛爾蘭語的人超過30%、甚至於一半以上 (Chriost,

2000a)。進一步考察會說愛爾蘭語的個人特色,89.4%是天主教徒 (Chriost,

2000a: Table 4),可見語言與族群認同/宗教信仰的相關;也就是說,雖然天主教徒不一定會講愛爾蘭語,不過,會講愛爾蘭語的人有很大的可能是天主教徒。此外,天主教徒普遍對於公領域的雙語(愛爾蘭語/英語)相當支持,譬如一般場所72.5%、上班地方60.0%,而新教徒的支持率分別是30.0%、13.3%;至於私領域的雙語,天主教徒贊成的高達90.0%,新教徒只有63.3% (Chriost,

2000a: Tables 5)。

值得注意的是在這些會講愛爾蘭語的人當中,44歲以下的人佔了78.1%,45歲以上的人只佔了21.8%,會說寫的有59.9%,只會說的佔34.4,可見愛爾蘭語的復育有相當的成就 (Chriost, 2000a: Tables 1, 2)。細究那些會講愛爾蘭語者的社會經濟背景,31.8%從事管理、或是科技的職業,33.8%擔任非手工的技術人員,不一定是低所得、或是不識字的鄉下人 (Chriost, 2000a: Tables 3)。

不過,Chriost (2000a) 提醒我們,會不會說愛爾蘭語、或是支持愛爾蘭語,與國家定位/民族認同、甚至於政治衝突的關係,並沒有表面上看來直接,也就是說,不會說愛爾蘭語者的「天主教族群/愛爾蘭民族認同」就一定比那些會講愛爾蘭語者來得低;事實上,有23%的新教徒認為中學應該有愛爾蘭語言、文化的課程。當然有些民族主義者相信愛爾蘭語可以跨越族群間的鴻溝,也就是即使無法使新教徒改變宗教信仰,卻可以改變他們的國家認同 (McCoy, 1997)。儘管如此,那些願意學習愛爾蘭語的人的新教徒,可能只是想想透過語言/文化,來確認自己在愛爾蘭這塊土地的定位,也就是「北愛爾蘭人」的認同,而非表示支持愛爾蘭民族主義 (Chriost, 2000a)。

參、語言政策的發展

根據Annamalai (2002),語言政策的目標可以根據光譜的分布分為消滅、容忍、以及推動。消滅性的語言政策就是以處罰的方式禁止某語言在公開場合、甚至於私下使用,用意是讓使用者覺得該語言是一種負債,轉而採取被認可的語言,最後達到語言轉移 (language shift),也就是同化的地步。顧名思義,容忍性的語言政策就是保持現狀,並未刻意去扶助弱勢族群的語言,也不想去扭轉跟隨語言而來的結構性不平等,甚至於就是令其自生自滅。推動性的語言政策就是想辦法避免任何語言的消失,包括鼓勵私下使用、或是確保公開使用而不被歧視。

英國在1921年同意愛爾蘭進行分割 (partition),讓西南方的26個郡成立「愛爾蘭自由邦[16]」(Irish

Free State),北方的6 個郡繼續留在聯合王國 (United Kingdom) 裡面,有自己的內閣制區域政府 (Stormont),由新教徒依多數決所控制。 Gallagher (n.d.)

把一直到1972年為止的北愛政府的文化政策歸納成三大特色:(一)既不想收攬天主教徒的心,也不想改變他們的信仰;(二)雖然不會禁止天主教徒的文化表現,但是不准其出現在公共場所,譬如禁止用愛爾蘭語當街道名稱[17];以及(三)刻意扶植新教徒的單一文化特色。我們可以看出來,北愛政府採取的是排他性的族群化政策,將新教徒的政治支配貫徹在文化表現,自然會引起天主教徒的反彈,愛爾蘭共和軍 (Irish Republican

Army, 簡寫為IRA) 甚至於以直接暴力來對抗結構性暴力。

根據O’Reilly

(1997) 的觀察,歷年來北愛爾蘭的語言政策論述可以歸納成先後發展的三大類:民族主義論/去殖民、文化認同論、以及語言權利論。持民族主義論者以為愛爾蘭語是對抗英國帝國主義的利器,因此,學習愛爾蘭語就是一種政治動作、說愛爾蘭語就是表達自己的愛爾蘭人認同。愛爾蘭開國英雄 Michael Collins就認為愛爾蘭語與愛爾蘭的獨立建國密不可分:

We only succeeded after we had

begun to get back our Irish way; after we had made a serious effort to speak

our own language; after we had striven again to govern ourselves. We can only keep out the enemy and all

other enemies by completing that task.

The biggest task will be the restoration of the Irish language

(O’Reilly, 1997).

新芬黨 (Sinn Féin)[18] 在1980年代積極傳播這種語言民族主義觀 (linguistic

nationalism);1981年獄中絕食致死的愛爾蘭共和軍成員Bobby Sanders之所以獲得浪漫式的同情,原因之一是他會講愛爾蘭語。相對之下,當時反對與愛爾蘭共和統一的北愛政府,對於愛爾蘭語的推廣就顯得意態闌珊。

北愛政府一向持文化認同論,雖然贊成語言有其負載認同、傳承文化的價值,卻反對把語言當作政治運動的工具。在過去,關心復振的工作者也同意將愛爾蘭語的政治色彩降到最低的程度,也就是在區隔文化民族主義、以及政治民族主義的前提下,嘗試以愛爾蘭語來結合各路人馬,同時避免讓主張聯合主義的新教徒產生威脅感。坦承而言,「去政治化」也是一種政治立場,特別是當這些人接受「語言=認同」之際,就無法擺脫語言的政治關聯。

目前,愛爾蘭語言推動者改採語言權利論,將語言當作最基本的人權,也就是認為講愛爾蘭語是天主教徒表達自由的形式之一。他們的做法是要將語言「多重政治化」(multipoliticize),也就是說,在無法假裝語言是政治中立的情況下,乾脆擴大接受其政治意義,除了接受愛爾蘭語的民族認同面向,也探索其族群認同、或是文化認同的可能,想辦法沖淡其愛爾蘭民族主義的成分。

在1970年代,英國一面力促北愛作政治妥協,同時出兵掃蕩IRA,卻始終是徒勞無功。在1980年代,主事者才漸漸體會到文化議題的重要性,也就是在用心著手致力於改善族群關係之際,開始覺得有必要將文化差異「正當化」,也就是承認族群間存在差異的事實,不再限制天主教徒的文化表現;此時,改弦更張的族群政策有三個特色:鼓勵雙方接觸、鼓勵對於多元文化的包容、以及促進機會均等 (Gallagher, n.d.)。在1985年簽訂的『英愛協定』(Anglo-Irish Agreement 1985)

當中,雙方同意為了調和 (accommodation) 北愛爾蘭兩個族群的權利、認同,保障其人權,以及避免歧視而作共同努力 (4-a-i、5-a)[19]。

在過去,光是靠政府分別對於兩個族群的文化活動挹注、忽略彼此的政治權力失衡,只會更加強化原本的隔閡,治本之道是想辦法達成「平等尊重」(parity of esteem);因此,在1980年代末期,語言議題開始被納入更為宏觀的政治脈絡去考量,也就是說,語言政策的目標不再是單純的文化資產保存,而是被寄望能發揮化解政治衝突(包括社會、經濟歧視)的功能 (Chriost, 2000a; Chríost, 2000b)。

隨著北愛爾蘭的和解腳步在1990年代加速,英國與愛爾蘭政府在1995年簽署『新架構協定』(New Framework for Agreement

1995),雙方同意合作的四個原則,包括自決、被統治者的同意、民主及和平的途徑,尊重、以及保障兩個族群的權利及認同,以及促成「平等的尊重暨待遇」[20]。雙方在1998年簽定的『北愛爾蘭和平協定』中同意將這些精神進一步法制化,根據平等的原則,也就是夥伴關係、機會平等、不受歧視、以及相互尊重彼此的認同下,簽署者承認到「尊重、了解、以及容忍語言多元的重要性,而愛爾蘭語、北愛蘇格蘭語 (Ulster –Scots)、以及各種族群的語言,都是整個愛爾蘭島上的文化財產」[21]。

誠如Chriost (2000b) 所言,『北愛爾蘭和平協定』當中的語言條款,終極的目標是化解兩個族群間的齟齬,因此,對於未來的語言政策作了相當詳細的規範。目前,英國政府除了同意將會儘快簽署『歐洲區域或少數族群語言憲章』(European Charter

for Regional or Minority languages 1992),特別應允「在適當的情況下、以及百姓的要求下」,採取積極行動來推廣愛爾蘭語、鼓勵愛爾蘭語在公私場合的說寫、解除對於愛爾蘭語維護發展的限制、提供操愛爾蘭語設群語官方的聯繫、訓示教育部鼓勵以愛爾蘭語作教學、探尋英國及愛爾蘭廣播機構的合作、資助愛爾蘭語電影及電視的製作[22]。根據Chriost (2000a) 的說法,就是設法提高愛爾蘭語的工具性,希冀在無形中降低敏感的象徵性意味。

英國國會在1998年通過『人權法案』(Human Rights Act 1998)、以及『北愛爾蘭法』(Northern Ireland Act 1998)

來落實和平協定。雖然語言權並未被列入基本人權的清單,不過,緊接著成立的「北愛爾蘭人權委員會」(Northern Ireland

Human Rights Commission) 被訓令儘快進行歐洲理事會『少數族群架構規約』(Framework

Convention for the Protection of National Minorities 1995) 的核准[23],同時著手起草一個『權利法案』,語言權被包含在內;人權委員會下面設有「語言權工作小組」(Language Rights

Working Group),也另外提出較詳盡的建議案[24]。

英國終於在2001年簽署『歐洲區域或少數族群語言憲章』,同意將愛爾蘭語列為Part III 的地位[25],也就是具有廣泛的實質效力,特別是具體的對於教育、司法、行政暨公共服務、媒體、文化活動暨設施、經濟暨社會生活、以及跨國交換等積極推廣措施 (Articles 8-14)。相對地,北愛蘇格蘭語只獲得Part II的象徵性地位,也就是原則性的承認、尊重、推廣、鼓勵、維護、發展、教學、研究、以及交換 (Article 7)。

當前北愛爾蘭政府[26]有關語言政策的部門如下 (BBC, n.d.; Gallagher, n.d.;Farren, 2000)。新設立的「文化、藝術、暨休閒部」(Department of

Culture, Arts, and Leisure,DCAL) 有一個「語言多元處」(Linguistic Diversity Branch[27]),負責推動『歐洲區域或少數族群語言憲章』的落實,算是協調性的單位。「第一總理暨副總理辦公室」(Office of the First

Minister/Deputy First Minister,OFMDFM) 關注的是廣義的如何促進族群間的和諧、以及公平。「教育部」(Department of

Education) 掌管各級學校以愛爾蘭語為學習用語的課程,下轄諮商性質的「愛爾蘭語學校理事會[28]」。再來,「族群關係理事會」[29] 在1990年就已經成立,下面設有「文化多元計劃」(Cultural Diversity Programme),負責撥款給社區辦相關活動。另外,根據『北愛爾蘭和平協定』,嶄新的「北南語言單位」(North/South

Language Body[30]) 也在1999年成立,直接向「北南部長理事會[31]」負責,下面分別設置「愛爾蘭語言局[32]」、以及「北愛蘇格蘭語言局[33]」,職責在愛爾蘭語/北愛蘇格蘭語的推廣、鼓勵公私場合的說寫、向公家機構或志願部門提供諮商、提供經費、進行研究、以及支助以愛爾蘭語/北愛蘇格蘭語為學習用語的教學。

肆、結語

Kirk與 Baoill

(2000: 11) 說:「語言學家與政客的定義當然不會相同,而語言學家與語言運動者對於分類、區隔也當然會有不同意見」,也就是說,「語言學定義≠政治認知≠官方承認」(頁6)。在北愛爾蘭的語言政策中,我們看到語言學家、政客、以及語言運動者的參與不遺餘力,也沒有偏廢任何一方。值得注意的是,北愛爾蘭人懂得運用國際輿論來推動少數族群的母語,譬如北愛選出的歐洲議員John Hume在1979年推動歐洲共同體草擬『區域語言文化人權法案』,終於在1981年獲得歐洲議會通過決議支持[34] (Ó Riagáin,

2002)。「歐洲鮮用語言協會」在1982年成立,其創會成員有很大的比重是關心愛爾蘭語的推動者(Ó Riagáin, 200: 67)。

儘管大眾/新教徒對於愛爾蘭語/雙語(英語、以及愛爾蘭語)的態度逐漸開放,多少還是對於愛爾蘭語的政治絃外之音戒慎小心;此外,對於愛爾蘭語在公共場所的使用,有些新教徒認為是一種歧視,或是感到不舒服,譬如用愛爾蘭語標示的招牌 (Chriost, 2000a)。最引起爭論的事件發生在女王大學 (Queen’s University) 的學生活動中心,由於打工的新教徒學生比率較低,加上活動中心公開懸掛愛爾蘭語標示,有學生因此抗議把宗教信仰、以及政治立場帶盡校園(Chriost, 2000a)。在進行愛爾蘭語「正常化」的過程中,仍然習慣於把文化差異「私人化」(privatize),傾向於限制多元文化在公共場所的呈現,好讓一般大眾覺得「自然」(comfortable),由此可見,北愛政府對於如何超越傳統的自綁手腳做法,仍然有待努力 (Gallagher, n.d.)。

FutzDuff (2000: 79) 指出,徒法不足以自行,完善的語言政策必須有配套措施。Farren (2000) 更不諱言指出,由容忍、承認、了解、到尊重,政府必須提供足夠的空間、資源、以及措施,不能只是口惠。『北愛爾蘭和平協定』採取「由下而上」的途徑[35],或許比政府主導的「由上而下」途徑更能鼓勵參與,然而,政府不可將此當作推託責任的依據 (Chriost, 2000b)。因此,公私部門間的分工如何取得適切的平衡,仍有很大的討論空間 (Dunbar, 2002),譬如說,儘管個人或社區主導語言的復振,或許可以培養自尊心、以及自信心,政府不能因此採取放任的態度,除了政策研究、以及規劃以外,政策的執行(特別是撥款補助)、考核,還是要仰賴政府部門的戮力。

附錄一、『北愛爾蘭和平協定』中的「語言條款」[36]

Rights,

Safeguards and Equality of Opportunity

3. All participants recognise

the importance of respect, understanding and tolerance in relation to

linguistic diversity, including in Northern Ireland, the Irish language,

Ulster-Scots and the languages of the various ethnic communities, all of

which are part of the cultural wealth of the island of Ireland.

4. In the context of active consideration

currently being given to the UK signing the Council of Europe Charter for

Regional or Minority Languages, the British Government will in particular in

relation to the Irish language, where appropriate and where people so desire

it:

• take resolute action to promote the language;

• facilitate and encourage the use of the language

in speech and writing in public and private life where there is appropriate

demand;

•

seek to remove, where possible, restrictions which would discourage or work

against the maintenance or development of the language;

• make provision for liaising with the Irish

language community, representing their views to public authorities and

investigating complaints;

• place a statutory duty on the Department of

Education to encourage and facilitate Irish medium education in line with

current provision for integrated education;

• explore urgently with the relevant British

authorities, and in co-operation with the Irish broadcasting authorities, the

scope for achieving more widespread availability of Teilifis

na Gaeilige in Northern

Ireland;

• seek more effective ways to encourage and

provide financial support for Irish language film and television production

in Northern Ireland; and

• encourage the parties to secure agreement that

this commitment will be sustained by a new Assembly in a way which takes

account of the desires and sensitivities of the community.

附錄二、『人權法案』草案中的「語言權條款」[37]

Language

Rights

1. Everyone has the right to

use his or her own language for private purposes and all languages, dialects

and other forms of communication are entitled to respect.

2. Everyone has the right to communicate with

any public body through an interpreter, translator or facilitator when this

is necessary for the purposes of accessing, in a language that he or she understands, information or services essential to his or

her life, health, security or enjoyment of other essential services.

3. The State shall make suitable provision for assisting

communication between members of different linguistic communities.

4. In relation to the Irish language and Ulster-Scots, legislation

shall be introduced to implement the commitments made under the Belfast (Good

Friday) Agreement and the European Charter for Regional and Minority

Languages.

5. Without prejudice to the foregoing provisions, legislation shall

be introduced to ensure for members of all linguistic communities, where

there is sufficient demand, the following rights in respect of their language

or dialect:

(a) the promotion of conditions necessary to maintain and develop it;

(b) the right to use it in

dealings with public bodies;

(c) the right to use one’s name in it and to be officially recognised under it;

(d) the right to display

signs and other information in it;

(e) the right to display local

street and other place names in it;

(f) the right to learn it and to be educated in

and through it.

附錄三、北愛爾蘭人權委員會語言權工作小組的建議案[38]

Language Rights Working Group

Advice to the

Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission

Language

use

Everyone

has the right to use the language of their choice and to participate in their

chosen social, economic, religious and cultural life but no-one exercising

these rights may do so in a manner inconsistent with any provision of the

Bill of Rights.

State

Recognition

The

State recognises the importance of respect,

understanding and tolerance in relation to linguistic diversity, including

Irish, Ulster-Scots, the languages of the deaf community and the languages of

the various minority ethnic communities, all of which are part of the

cultural wealth of the island of Ireland.

Definitions

For

the purposes of this Bill indigenous languages shall be taken to include

Irish, Ulster- Scots, Cant/Gammon (the language of the Traveller

community), British and Irish sign languages and English. Ethnic community languages shall be

taken to include Arabic, Bengali, Cantonese, Gujurati, Hakka, Hindi, Mandarin, Punjabi, Swahili, Urdu

(and any other such languages).

Other communication modes shall include Braille or any other necessary

means of communication arising through disability. ‘Person belonging to a linguistic

community’ shall be taken to mean a person using any one of these forms of

communication.

Guarantee

of existing or future rights

The

provisions of this Bill of Rights shall not affect more favourable

provisions concerning the status of indigenous or minority ethnic languages

or the legal regime of any persons belonging to a linguistic community under

previous legal agreements or which are to be provided for by relevant current

or future international bilateral or multilateral international

agreements.

Non-discrimination

Every

person belonging to a linguistic community shall have the right to use their

language in public and in private life with no unjustified distinction,

exclusion, restriction or preference intended to discourage or endanger the

maintenance or development of the language.

Non-assimilation

Every

person belonging to a linguistic community has the right to maintain their

own language free from any State policies or practices aimed at assimilation

of persons belonging to such communities against their will.

State

duties - qualifications

In

the implementation of the State’s duties the State may take into

account:

·

Usage (numbers or geographical

concentration)

·

Need

·

Demand

·

Practicality

·

The situation of each language

State

duties

The

State must:

·

Recognise the historically diminished use and status of

indigenous languages of our people in relation to the English language.

·

Take practical and positive measures

to elevate the status and advance the use of these languages through

legislation, policy and practice.

·

Promote

and create conditions for the development and use of all indigenous

languages.

·

Recognise the importance of their native language to the

various minority ethnic communities.

·

Promote and ensure respect for the

various languages of the minority ethnic communities.

·

Promote and ensure respect for other

communication modes.

·

Make available in indigenous or

minority ethnic community languages and in Braille and other communication

modes the most important national statutory texts and those relating

particularly to users of these languages.

·

Ensure that local or regional authorities

make available in indigenous or minority ethnic community languages or

relevant communication modes the most widely used administrative texts, forms

and documents and those relating particularly to users of these languages.

·

Ensure that, with regard to public

services provided by local or regional authorities or other persons acting on

their behalf, indigenous or minority ethnic community languages or relevant

communication modes are used in the provision of the service, and ensure

that, with a view to putting into effect this provision, translation or

interpretation services and necessary recruitment and training of officials

and other public service employees is undertaken.

·

Ensure

that, whilst respecting the principle of the independence and autonomy of the

media, adequate provision of regular radio and television broadcasting

delivered in or about indigenous or minority ethnic community languages is

undertaken by broadcasters.

·

Encourage

and/or facilitate the production of audio, visual, and audiovisual material

in the indigenous languages.

·

Encourage

and/or facilitate the development of and access to information communication

technologies for all linguistic communities.

·

Encourage

and/or facilitate the creation and/or maintenance of at least one newspaper,

and/or facilitate the publication of regular newspaper articles in indigenous

languages.

·

Provide

for the use or adoption, if necessary in conjunction with existing legal

names, of the traditional and correct forms of placenames

and/or streetnames in indigenous or minority ethnic

community languages.

·

Appoint

a Language Ombudsman who will be responsible for monitoring and evaluation

of:

·

The

quality, level and suitability of language services;

·

The

appropriateness of organisational structures and

other arrangements by public sector bodies for delivering services to

indigenous and minority ethnic community language users or users of other

communication modes;

·

Complaints

from the public with regard to language services.

Names

Every

person belonging to a linguistic community has the right to use their own

surname and first names in their language and the right to official

recognition of them.

Judicial

Rights

Every person

belonging to a linguistic community has the right, in civil or criminal

proceedings:

·

To use their own language.

·

To be guaranteed that requests,

documentation and evidence, however presented, shall not be considered

inadmissible solely because they are formulated in their own language and

that translations, if required, shall not involve extra expense for the

person(s) concerned.

·

To be guaranteed that the courts will

produce, on request, documents connected with legal proceedings in the

relevant language, if necessary by the use of interpreters and translations

involving no extra expense for the person(s) concerned.

·

Draft legal documents in their own

language and to be guaranteed that where these are invoked in legal proceedings

there should be no extra expense to the person(s) concerned.

·

Draft legal documents in their own

language and to be guaranteed that they can be invoked against interested

parties who are not users of these languages on condition that the contents

of any document are made known to them by the person(s) who invoke(s) it.

·

Be informed promptly, in a language or

communication mode he or she understands, the reasons for his or her arrest,

and of the nature and cause of any accusation against him or her, and to

defend himself or herself in this language or communication mode, if

necessary with the free assistance of an interpreter.

Judicial

qualification

No-one

exercising these rights may do so in a manner inconsistent with any provision

of the Bill of Rights.

Education

Every person

belonging to a linguistic community has the right to:

·

Set up and manage their own private

educational and training establishments.

·

The State provision of appropriate

forms and means for the teaching and study in or of indigenous or minority

ethnic community languages at all levels of education (i.e. pre-school,

primary, secondary, technical and vocational, university and adult and continuing

education).

·

The State provision of the teaching of

the history and culture which is reflected by indigenous languages.

·

The State provision of facilities

enabling non-speakers of indigenous or minority ethnic community languages to

learn them if they so desire.

·

Resolute action in the fields of

education and research to foster knowledge of the culture, history and

language of their own and other linguistic communities.

·

Assistance whereby when any member of

a linguistic community is unable to communicate with the wider community the

State will make suitable educational provision to enable him or her to do so.

Administrative

and Public Authorities

Every person

belonging to a linguistic community has the right to make applications and

submissions to administrative authorities and to receive a reply in their own

language or communication mode.

Media

Every person

belonging to a linguistic community has the right to:

·

Set up and manage their own media

within the legal framework for print, sound radio, film, television and

computer broadcasting/media.

·

Freedom of direct reception of radio

and television broadcasts from other countries in a language used in

identical or similar form to an indigenous or minority ethnic community

language, and to freedom of expression and free circulation of information in

the written press or electronic broadcast media in a language used in

identical or similar form to an indigenous or minority ethnic language with

no State restrictions subject to such formalities, conditions, restrictions

or penalties as are prescribed by law and are necessary in a democratic

society, in the interests of national security, territorial integrity, public

safety, for the prevention of disorder or crime, for the protection of health

or morals, for the protection of the reputation or rights of others or for

maintaining the authority or impartiality of the judiciary.

·

Have their interests represented or

taken into account within such bodies as may be established in accordance

with the law with responsibility for guaranteeing the freedom and pluralism

of the media.

Exercise

of Rights

Every person

belonging to a linguistic community may exercise these rights and freedoms

individually as well as in groups / community with others.

相關文件(依時間先後)

European Parliament

Resolution on a Community Charter of Regional Languages and Cultures and on a

Charter of Ethnic Minority 1981. (http://www.friul.net/ normative/arfe.html。

European Charter for

Regional or Minority languages 1992. (http://www.coe.fr/eng/ legaltxt/148e.htm)

New Framework for

Agreement 1995.

(http://www.irlgov.ie/iveagah/angloirish/

frameworkdocument/default.htm)

A Framework for Accountable Government in Northern Ireland 1995. (http://www2. nio.giv.uk/framwork.htm)

Framework Convention

for the Protection of National Minorities 1995. (http://www. coe.fr/eng/legaltxt/157e.htm)

Northern

Ireland Peace Agreement 1998 (Belfast Agreement、或Good

Friday Agreement).(http://www.irish-times.com/irish-times/paper/1998/0410/agreement.

html、或http://www.nio.gov.uk/issues/agreement.htm)

Human

Rights Act 1998.

(http://www.hmso.gov.hk/acts/acts1998/19980042.htm)

Northern

Ireland Act 1998.

(http://www.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1998/19980047.htm)

Oslo Recommendations

Regarding the Linguistic Rights of national Minorities and Explanatory Note

1998. (http://www.unesco.org/most/ln2pol7.htm)

UK Report on the

Council of Europe Framework Convention for the Protection of National

Minorities 1999 (http://www.humanrights.coe.int/Minorities/Eng/

FrameworkConvention/StateReports/1999/uk/P…)

參考文獻

北愛爾蘭人權委員會。2001。《北愛爾蘭人權法案的提議》。Belfast: Northern Ireland

Human Rights Commission.

Andrews, Liam. 2000. “Northern Nationalists and the

Politics of the Irish Language: The Historical background,” in John J. Kirk,

and Dónall P. Ó Baoill, eds. Language and Politics: Northern Ireland, the

Republic of Ireland, and Scotland, pp. 43-63. Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast, Cló Ollscoil na Banríona.

Annamalai, E. 2002. “Language Policy for Multilingualism.”

Paper presented at the World Congress on Language Policies, Barcelona, 18-20

April. (http://

www.linguapax.org/congres/plenaries/annamali. html)

Arthur, Paul. 1980. Government and Politics of Northern

Ireland. Burnt Mill, Harlow,

Essex: Longmna.

BBC. n.d. “Promotion of the Irish

Language.” http://www.bbc.co.uk/ northernireland/education/stateapart/agreement/culture/irish1.shtml.

CAIN. 2002. “Background Information on Northern

Ireland Society - Population and Vital Statistics.”

(http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/ni/popul.htm)

Chriost, D. MacGiolla.

2000. “The Irish Language

and Current Policy in Northern Ireland.”

Irish Studies Review, Vol. 8, No. 1. (EBSCOHost)

Chríost, Diarmait MacGiolla. 2000. “Planning Issues for Irish Language

Policy: ‘An Foras Teanga’

and ‘Fiontair Teanga’.” (http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/

languages/macgiollachriost00.htm)

Cunningham,

Michael. 2001. British Government Policy in

Northern Ireland. Manchester:

Manchester University Press.

De Varennes, Fernand. 2001. “Language Rights as an Integral Part

of Hman Rights.” MOST Journal of Multicultural

Societies, Vol. 3, No.1.

De Varennes, Fernand. 1997. To Speak or Not to Speak: The

Rights of Persons Belong to Linguistic Minorities.

(http://www.unesco.org/most/ln2pol3.htm)

De Varennes, Fernand. 1996. Language, Minorities and Human Rights. Dordrecht: Martinus

Nijhoff.

Doherty, Paul. 1996. “The Numbers Game: The Demographic

Context of Politics,” in Arthur Aughey, and Duncan

Morrow, eds. Northern Ireland Politics, pp. 199-209. London: Longman.

Dunbar, Robert. 2002. “Minority language Legislation and

Rights Regimes: A Typology of Enforcement Mechanism.” Paper presented at the

World Congress on Language Policies, Barcelona, 18-20 April. (http://www.linguapax.org/

congres/taller/taller1/article6_ang.html)

Farren, Seán.

2000. “Institutional

Infrastructure Post-Good Friday Agreement: The New Institutional and Devolved

Government,” in John J. Kirk, and Dónall P. Ó Baoill,

eds. Language and Politics: Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and

Scotland, pp. 121-25.

Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast, Cló Ollscoil na Banríona.

FitzDuff, Mari. 2000. “Language and Politics in a Global

Perspective,” in John J. Kirk, and Dónall P. Ó Baoill, eds. Language and

Politics: Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and Scotland, pp.

75-80. Belfast: Queen’s

University Belfast, Cló Ollscoil

na Banríona.

Gallagher,

Tony. n.d. “Culture and Conflict in Northern

Ireland.” (http:// www.coe.int/T/E/Cultural_Co-operation/Culture/Other_projects/Intercultural_Dualogues_a…)

Hadden, Tom. 2000. “Should a Bill of Rights for Northern

Ireland Protect language Rights?” in John J. Kirk, and Dónall P. Ó Baoill,

eds. Language and Politics: Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and

Scotland, pp. 111-20.

Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast, Cló Ollscoil na Banríona.

Human Rights

Watch. 1998. “Justice for All? An Analysis of the Human Rights

Provisions of the 1998 Northern Ireland Peace Agreement.” (http:// www.

hrw.org/reports98/nireland/)

Kirk, John J., and

Dónall P. Ó Baoill. 2000. “Introduction: Language, Politics and

English,” in John J. Kirk, and Dónall P. Ó Baoill, eds. Language and

Politics: Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and Scotland, pp.

3-12. Belfast: Queen’s University

Belfast, Cló Ollscoil na Banríona.

Language Rights

Working Group. n.d.

“Language Rights Working Group Advice to the Northern Ireland Human

Rights Commission.” (http://www.nihr.org/ files/wgr_Language_1.htm)

McCoy, Gordon. 1997. “Protestant Learners of Irish in

Northern Ireland,” in Aodán Mac Póilin,

ed. The Irish Language in Northern Ireland. (http://

cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/language/macoy97.htm)

Morrow, Duncan. 1996. “Churches, Society and Conflict in

Northern Ireland,” in Arthur Aughey, and Duncan

Morrow, eds. Northern Ireland Politics, pp. 190-98. London: Longman.

Northern Ireland

Human Rights Commission.

2001. Making a Bill of

Right for Northern Ireland.

Belfast: Northern Ireland Human Rights Commission.

Northern Ireland

Human Rights Commission. n.d. “The

Bill of Rights Language.” (http://www.nihrc.org/files/BoR_Language_1.htm)(與Hadden內容雷同)

Ó Murchú, Helen.

2000. “Language,

Discrimination and the Good Friday Agreement: The Case of Irish,” in John J.

Kirk, and Dónall P. Ó Baoill, eds. Language and Politics: Northern

Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and Scotland, pp. 81-88. Belfast: Queen’s University Belfast, Cló Ollscoil na Banríona.

Ó Riagáin, Dónall. 2002. “Irish – Official Yet Lesser Used.”

Paper presented at the World Congress on Language Policies, Barcelona, 18-20

April. (http:// www.linguapax.org/congres/taller/taller3/article21_ang.html)

Ó Riagáin, Dónall. 2000. “Language Rights as Human Rights in

Europe and in Northern Ireland,” in John J. Kirk, and Dónall P. Ó Baoill,

eds. Language and Politics: Northern Ireland, the Republic of Ireland, and

Scotland, pp. 65-73. Belfast:

Queen’s University Belfast, Cló Ollscoil

na Banríona.

O’Reilly,

Camille. 1997. “Nationalists and the Irish Language

in Northern Ireland: Competing Perspective,” in Aodán

Mac Póilin, ed. The Irish Language in Northern

Ireland. (http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/language/oreilly97.htm)

Packer, John. 2002. “Towards Peace, Dignity and

Enrichment: Language Policies in the 21st Century.” Speech

delivered at the World Congress on Language Policies, Barcelona, 18-20 April.

(http://www.linguapax.org/congres/packer.

html)

“Political

Demography in Northern Ireland.”

c. 2001. (http://www.geocities.com/

pdni/demog.htm)

Rose, Richard. 1976. Northern Ireland: Time of Choice. Washington, D.C.: American Enterprise

Institute of Public Policy Research.

Sutherland, Margaret

B. 2000. “Problems of Diversity in Policy and

Practice: Celtic Languages in the United Kingdom.” Comparative Education, Vol. 36,

No. 2. (EBSCOHost)

TOP

|