|

Emerging Taiwan-America-Japan Triangular Relations* |

||

|

Cheng-Feng Shih, Associate Professor Department of Public Administration, Tamkang

University Associate Researcher, Taiwan National Security Institute

|

||

|

Taiwan’s National Security

Strategies Since the end of

World War II, as Communist China has never ceased coveting over Taiwan’s

territory,[1][1] the national interests of Taiwan have

been largely defined by how it has successfully guarantee its national

security.[2][2]

At different stages, various national securities have been suggested

or implemented in Taiwan, which may be understood from either Realist or

Idealist perspective in the International Relations theories.[3][3] From the vintage

point of Idealism, especially Neo-liberal Institutionalism, collective

security mechanism, global or regional, may be warranted to deter the

expansionism of potential aggressors with military pacification. However, because of the obstruction

from Russia and China, who possess the veto power within the Security Council

of the United Nations, the universal application of the collective security

instrument has unfortunately so far been circumscribed. For the past decade, Taiwan has

persistently sought to reenter/join the UN, ostensibly in the hope to walk

out of international isolation imposed by the People’s Republic of China

(PRC). In fact, one of the most

important considerations is to internationalize the peace and security of the

Taiwan Straits by actively taking part in the happenings in the international

society. Again, because of the

uncompromising boycott by China, Taiwan has so far failed to make its telling

presence in the UN arena, not to mention the application of UN collective

security measure just in case China should wage a war against Taiwan. Although former President Lee Ten-hui had in the past relentlessly called for the

establishment of an Asian collective security arrangement, one precondition

of such a security structure is the consent from the great power of East

Asia, that is, Japan and China, as well as the approval from the lone super

power in the world, the United States. Alternatively, some

have unwaveringly proposed robust engagement with the ASEAN countries, a

strategy formally pronounced as “Southward Policy.” While the ASEAN established a Regional

Forum (ARF) in 1994, with an eye to conduct multilateral official dialogues

on security issues, particularly the exercise of preventive diplomacy,[4][4] it is still far away from

institutionalization as developed in the Organization for Security and

Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). As

is well known, the US had during the Cold War era preferred bilateral

cooperation to multilateral security framework. While it has demonstrated more

comfortable disposition toward multilateralism, it is yet not clear whether

the US would have any slight idea in contemplating the ARF for alleviating

the tension between China and Taiwan.

Also, as an acquisitive dragon on their borders, it is doubtful these

wary ASEAN nations would offer Taiwan any opportunity for its presence. Moreover, Taiwan has in the past shown

scanty attention to its ASEAN neighbors, it would be laborious for Taiwan to

become member simply based on geographical and ethnic Malayo-Polynesian

affinities.[5][5] A third approach is “Westward Policy” in the spirit of functionalism. Inspired by the development of integration in West Europe, its proponents have preached that trade and economic cooperation with China may eventually be conducive to the ease of political rivalry and military conflict between Taiwan and its Chinese adversary. Nonetheless, the cleavages between the two are not confined to territorial disputes only. Underneath Chinese hostility toward Taiwan is its violent opposition toward Taiwan’s legitimate existence in the international society, which is not going to pass into oblivion because of economic exchanges. In addition, as there exist enormous socio-economic disparities and disproportion in territorial size between Taiwan and China, disparate from those between France and Germany, any vulgar analogy is bound to shut one’s eyes to the issue of vulnerability resulting from Taiwan’s economic dependency on China. Wary of economic security on Taiwan’s part, former President Lee Ten-hui espoused a Neo-mercantilist economic policy toward China. Given the fact that China the only country is the world that has openly waged military threat against Taiwan, Lee’s purposeful selection of trade restraints is understandable. Nevertheless, the current Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), which came to power in May 2001, has adjusted Taiwan’s thus far protective economic stance toward China, probably under the ceaseless pressure from Taiwanese businessmen who expect to gain from direct links with China. Some, apprehended by the conception of Neofunctionalism, have gone so far as to aspire the eventual goal of political unification with China as a result of deepened economic integration.

A fourth

strategy has been faithfully followed in pursuant to the basic tenet of

Realism, that is, how to obtain self-help through balance-of-power in the

anarchic international system (Waltz, 1979), and to safeguard national

security, conceived as military power, through forming collective defensive

alliance. During the Cold War

era, the US managed to forge bilateral and multilateral military alliances

with its allies all over the world to contain the Communist bloc. Within that bipolar competition

buttressed by nuclear capabilities, Taiwan’s security was essentially

guaranteed through its Mutual Defense Treaty with the US.[6][6]

Although the US was forced to terminate its formal military and then

diplomatic relations with Taiwan in the 1970s, a Taiwan Relations Act[7][7] was passed by was US Congress to

maintain continuous relationship with Taiwan in 1979. Even though the US has deliberately

avoided any explicit military commitment to defend Taiwan, the

peace-enforcement stipulations implied within the TRA framework have rendered

the US-Taiwan relations into some quasi-military alliance as testified in the

1995-1996 missile crises across the Taiwan Straits.[8][8] As the international

system has undergone drastic structural changes with the demise of the Soviet

Union in 1991, China’s relative importance in American calculation of global

strategy has been effectively dwindled.[9][9]

While Chinese military spending had remained stable in the 1980s, it

began to grow at a greater pace.

So far, watchful American Sinologists have not reached any consensus

regarding whether Chinese military modernization would cause any threat to

the US.[10][10]

Still, the Guidelines for Japan-US Defense Cooperation[11][11] promulgated in 1997 was

perceived for military consolidation in order to maintain acceptable

balance-of-power in East Asia, if no to contain China.[12][12]

Within this new configuration, Taiwan may probe the possibility to

further mutual military linkage with Japan based on hitherto solid military

alliance between Japan and the US.

An emerging Taiwan-US-Japan collective defense bund, thus, may help to

upgrade current American security commitment to Taiwan. In so conception, “Eastward Policy” is

still the ultimate insurance for Taiwan’s national security. However, as the military is still

engulfed in unyielding anti-Japanese sentiment, if not resentment, left over

from the former Nationalist Chinese government of the Chiang’s, “Northward

Policy” had in the past not been seriously undertaken. Evolving American Policy

toward Taiwan Since the conclusion

of World War II in 1945, the United States has witnessed eleven

administrations, from Truman to Bush, and its relationship with

Taiwan/Republic of China (ROC) has undergone fluctuating alternation. The honeymoon between the two

countries from the wartime alliance plumped to the lowest point in 1949 when

the Truman administration adopted its hand-off policy toward the Chinese

civil war and waited to see the annexation of Taiwan by the Communist

Chinese. After t the Korean War

in 1950, when the Seventh Fleet was dispatched to protect Taiwan, the

American policy was unexpectedly reversed. The Taiwan-America relations turned

into a military alliance and thus reached its peak when a Mutual Defense

Treaty was signed in 1954. By and

large, the Kennedy and Johnson administrations retained closer relations with

Taiwan, especially during the heydays of the Vietnam War. However, once the Nixon and Ford

administrations were resolved to court China in faithful pursuit of Kissinger’s

grand strategy of fighting an one-and-half war

against the Soviet Union, Taiwan was gradually abandoned. The amiable relationship came to

another slump in 1979 when the Carter administration decided to derecognize

the ROC and established foreign relation with the PRC. Regardless, the TRA

was promulgated in the same year, which stands as the watershed of American

policy toward Taiwan. Before the

TRA, Taiwan had long been treated as but one component of the American global

strategic thinking to counter the PRC.

Thereafter, the US has been more inclined to look at its separate

relations with Taiwan detached from China although American considerations in

these days have to be constrained by Chinese claim of Taiwan’s territory in

their mutual pursuit of accommodation. So far, the most

important indicator of the evolution of American policy toward Taiwan has

been American contemplation of the legal status of Taiwan. Until 1950 the US had persistently

taken the position that Taiwan was part of China. To justify its protection of Taiwan

after the outbreak of the Korean War, the Truman administration declared that

the legal status of Taiwan was uncertain and should be settled

internationally. The policy

lasted until 1972 when the US formally acknowledged

in the Shanghai Communiqué[13][13] that “all Chinese on either side of

the Taiwan Strait maintain that there is only but China and Taiwan is a part

of China.” In the 1979 Joint

Communiqué on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between the United States

and the People Republic of China,[14][14] the US “acknowledge the Chinese position that there is but one China and

Taiwan is part of China.”

Similarly in the 1982 U.S.-China Joint Communiqué,[15][15] it is reiterated that the US “acknowledged the Chinese position

that there is but one China and Taiwan is part of China.” (emphases added) While the so-called

“One China Policy” has been embodied in the “Three Communiqués” between the

PRC and the US, of which the contents may have varied and been subject to different

interpretations over the years with changing contexts, it is categorically

different from the “One China Principle” espoused by China. Rationally speaking, one China carries

a host of connotations along the spectrum from One China=PRC (Taiwan

incorporated), One China=Two Governments (CCP &

KMT/DPP), One China=ROC, One China=Historical,

Cultural, Geographical China, and One China=One China+One Taiwan. Still, it must be pointed out that the

TRA has nothing like “Taiwan is a part of China.” Since not all interpretations are

contradictory, the US has long chosen to keep all options open to be decided

by Taiwan and China themselves.”

Since “One China Policy” does not necessarily negate the possibility

of recognizing a Republic of Taiwan, this purposeful ambiguity has left an

ample space for proponents of the Taiwan Independence Movement in their

pursuit of establishing an independent Republic of Taiwan. The other

manifestation has been American commitment to Taiwan’s defense as stipulated

in the TRA. Although the

administrations since Carter have calculated to be vague over whether the US

would send troops to defend Taiwan in case of war, peaceful resolutions

between the Straits of Taiwan has so far been faithful followed. As the US has

designated in the TRA that the security issue of Taiwan is beyond any

challenge, the TRA has been unconditionally invoked to demonstrate American

commitment to defend Taiwan, suggesting its primacy over the 817 Communiqué,

which was vividly demonstrated in the 1995-96 Missile Crises, when Clinton

sent Nimitz and Independence to deter China, testifying again that the

security of Taiwan as guaranteed in the TRA outweighs other policy

considerations. This entrustment

is further reinforced after the revised U.S.-Japan Defense Guideline was

promulgated in 1997. In the main, the

Clinton administration adopted a strategy of “Comprehensive Engagement” with

China in the post-Cold War era. A devastating punch come from the “Three No’s” during

Clinton’s visit in China in 1998.[16][16]

On the other hand, President George W. Bush no longer considers China

as a “constructive strategic partner,”[17][17] but rather a competitor in a global

strategic design focused on the Asian-Pacific region, which has been

certified the recently released Annual Report on the Military Power of the

Peoples’ Republic of China prepared by the American Department of

Defense,[18][18] and the report to Congress of the

US-China Security Review Commission, entitled the National Security

Implications of the Economic Relationship between the United Stats and China.[19][19]

So far, while President Bush has shown his reluctance to mention the

three, now out of date, Communiqués, he has also recurrently demonstrated his

goodwill toward Taiwan. For

instance, he openly pledged to do “whatever it took to help Taiwan defend

herself” in case China attack Taiwan,[20][20] promised to help Taiwan joining the

World Health Organization (WHO), and even referred to Taiwan as “Republic of

Taiwan.”[21][21] Before he embarked on his trip to East

Asia in April 2002, he called attention to Taiwan as “good friend” along with

Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand, and the Philippines.[22][22]

While speaking to the Japanese Diet, he reiterated American

“commitments to the people on Taiwan.”[23][23]

At a press conference in Beijing, he brought up the Taiwan Relations

Act in front of Chinese President Jiang Zemin[24][24]; again, he wasted no time reminding

the Chinese audience of the American “commitment to Taiwan” and avouching

American determination to “help Taiwan defend herself if provoked” by

invoking the Taiwan Relations Act while delivering a speech in Tsinghua

University, Beijing.[25][25]

In return for Chinese clamor for “peaceful unification,” he retorted

with such expressions as “peaceful settlement” and “peaceful settlement.” Although American

Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz was recently forced to answer that

the US does “not support independence for Taiwan” while challenged by a

compound question uttered by a journalist from Taiwan,[26][26] he was said to have expressed regretfulness for any inconvenience incurred to the

Taiwanese. Regarding the standard

responses in the form of “being opposed to” or “not to support” Taiwan

independence, we may come with two rational interpretations. For one thing, while the US would not

allow China to swallow Taiwan because of American interest, it leaves up to

the Taiwanese to decide whether they would get rid of the iron cage under the

Republic of China. Furthermore,

it is beneficial to the Taiwanese if the US openly unveil her intention not

to involve herself on the issue of Taiwan independence as the Chinese would

not have any opportunity to accuse the US meddle in Taiwanese exercising

their right to self-determination. In retrospection,

the relationships between the US and Taiwan in the past two decades had been

amount to a quasi-alliance in short of the status of free association. What remains to be seen is whether or

not the US would protect, if not to send troops to Taiwan, in case China

should invade the island after Taiwan has formally declared independence. Seven Scenarios to the Future Based on the Structural Realist perspective

of Kenneth Waltz (1979), we have shown that the dyadic US-Taiwan interaction

may be treated as one link of the regional US-China-Taiwan triangle in East

Asia, which in turns until the later 1990s been dependent on the

configuration of the global US-USSR-China triangle. When the structure of the global system

changed, manifested in terms of the realignment of the three Powers, the

parts had to adjust themselves in order to preserve their own interests. These adjustments in turns led to

structural changes in the regional sub-system whence the units in the

sub-system again needed to rearrange their positions. These dynamics largely explain the US

policy toward Taiwan over the 50 years. In the period of

1945-91, the global triangle[27][27] was composed of the US, the USSR, and

China, while the regional one in East Asia is made of the US, China, and the

Taiwan. We may view the Taiwan-US

relationship as but a link of the China-US-Taiwan triangle, which is in turns

dependent on the global USSR-US-China triangle. When the structure of the global

triangle varies, the three actors in the former triangle have to adjust among

themselves. The global triangle

had evolved from a balanced triangle or a quasi-bipolar (US vs. USSR+China) in the 1960s, to an unstable and loose

triangle in the 1970s, and finally to another balanced triangle or an embryo

bipolar matrix (US+China vs. USSR) in the

1980s. The regional

China-US-Taiwan triangle had subsequently evolved from a stable one in the

1960s and, to a less degree in the 1970s, to an unstable one in the 1980s. Even with the breakup of the USSR in

1991 and the US left as the lonely superpower, the regional triangle in East

Asia has largely remained the same. The Taiwan-US

relationship, evolving from tight military allies to loose partners, has

basically a function of fundamental structural changes of the international

system. Although the asymmetric

relationship between the US and Taiwan has stayed relatively the same since

1950, the stability is slightly fluctuating. The structure of the global triangle

underwent a spectacular change in the late 1960s when the feud between the

two communist partners turned into war.

The development offered a favorable opportunity for the rapprochement

between the US and China. After

the US-China normalization in 1979, the global structural change entailed the

restructuring within the regional triangle. With the demise of the Soviet Empire,

the importance of China as an American counterweight against the USSR has

disappeared. At the regional level,

this means the US will be less willing to compromise on the Taiwan

issue. Logically, the

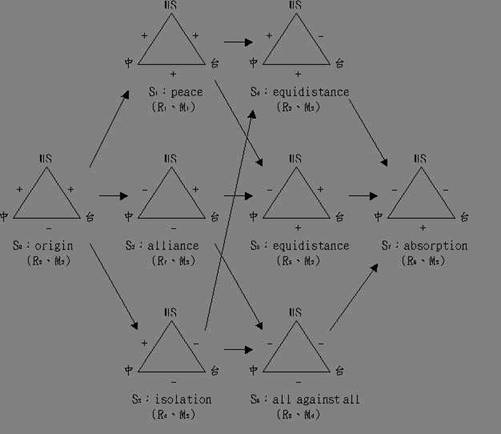

triangular relationship may have eight possible configurations. We may classify them into four modes: ménage

à trios, romantic triangle, stable

marriage, and mutual exclusion.

According to cognition theory, while ménage

à trios and stable marriage are stable

relationships, romantic triangle and mutual exclusion are unstable ones (Heider, 1946).

See Dittmer (1981) for the discussion of the former three. Starting with the

current unstable regional triangle (S0 in Figure 2), we may come

up with seven possible scenarios for the US-China-Taiwan relationships: S1,

S2, and S3 are first-order derivations, S4,

S5, and S6 are second-order ones,

and S7 is a third-order one.

It is noted that while the three second-order modes are unstable, the other four modes are stable. It is assumed that high-level

derivation is less tenable since more efforts are needed in order to

transform the configurations sequentially. If the positive

Taiwan-US relationship is to be maintained, in order to maintain a balanced

regional triangle, there are two possibilities: either the PRC-Taiwan link is

transformed into friendly one (S1), or the PRC-US link has to

shift back to inimical one as in the 1960s and 1970s (S2). Judging from the recent development of

growing strategic need and economic ties between the US and the PRC, their

relationship can only grow closer and hence the latter possibility seems less

probable. This leaves the former

option, that is, a harmonious PRC-Taiwan relationship, more tenable. On the other hand,

is it conceivable that the Taiwan-US relationship should turn sour or

negative in the context of a balanced regional triangle? One can imagine the possibility that

the US should decide to embrace the PRC in all respects and to turn its back

on Taiwan (S3). To

attain regional balance under this configuration, the US has to sacrifice its

economic tie with Taiwan and scratch its moral commitment underwritten in the

Taiwan Relation Act. S4 may

develop from S1 or S3. First of all, for some unknown

reasons, the amicable US-Taiwan relationships embedded in the peaceful

regional triangle turn sour while China keep equal cordial relations with

both the US and Taiwan. In this

sense, a seemingly tranquil triangle East Asia may be transient; if the

peacemaking between China and Taiwan is not endorsed by the US, this

settlement may turn out costly for Taiwan since the US would back away from

its security commitment. Secondly, Taiwan may

decide to embrace China after desperately perceiving isolated by both China

and the US, which means China comes to Taiwan’s rescue in the latter’s

diplomatic isolation. In some

sense, the transformations represent Taiwan’s determination to switch its

friendship from the US to China.

It will take place only when the Taiwanese feel obliged to integrate

with China because of economic, political, or cultural affinities. One can imagine when the above

conditions will be made: economic prosperity, political democracy, or cultural

identity. At this point, it all

depends the Taiwanese what is their thought to have their own body political

Taiwan. S5 may arrive from S1 or S2. For one thing, the seemingly untroubled regional triangle may grow unstable because of the rift between the US and China somehow deteriorates and turns into full-scale conflicts. This is highly probable given the undisguised competition between the two giants in all spheres after the breakup of the Soviet Union. At this juncture, Taiwan has to strike a delicate balance between the US, a longtime allay, and China, a hegemonic neighbor. First-order Second-order Tired-order

Figure 2: Seven Scenarios to the Future Alternatively,

Taiwan may seek to improve its relationships with China after Taiwan’s

alliance with the US is firmly secured.

This contour may take place when an isolated China seeks to break the

impasse by making peace with Taiwan.

At this juncture, it is imperative that Taiwan should obtain understanding

fro the fraternal US; otherwise, a neglectful US

may feel unwilling to render its support in case a ready China makes up its

mind to absorb Taiwan. S6 may

follow from S2 or S3. In the beginning, Taiwan may take

steps to secede its cooperation with the US even when China, Taiwan’s foe,

collides with the US. This is an

unwise calculation for Taiwan by giving up its only patron in this

region. On the other hand, the

development may be conceived an improvement from total isolation by both the

US and China. At least, Taiwan

does not have to fight a two-front war with collaborated China and the

US. In other words, the

relinquishment of the relationships with the US can only be barely

compensated by an equally disruption of those between the US and China. The least plausible

scenario is the one that the PRC-Taiwan link somehow turns amicable, such as

a forced unification, and the PRC-US link turns hostile (S7). This configuration is less probable in

two counts: firstly, the development is not called for by the US unless it

finally comes to conflict with the PRC; and secondly, a rift between the US

and Taiwan is against American national interest given the enormous economic

stakes on the island. In our assessments,

Taiwan’s preference would be: S1>S2>S5>S0>S4>S6>S3>S7. From the standing

point from Taiwan, whether peace (S1), alliance with the US (S2),

or even equal distance with the US and China (S5) is an

improvement of the status quo (S0). Since peace (S1) and

alliance (S2) are stable configurations, they would yield more

utility than does equidistance (S5); furthermore, equidistance (S5)

would suggest degrade relationships with the US and thus is deemed less

acceptable than peace (S1) and alliance (S2). Moreover, any frames whence Taiwan

would dispute with the US (S4, S6, S3, and S7)

are considered deviated from the statues quo (S0). While Taiwan’s absorption by China is

totally undesirable, hostile US-China relations (S6) are

better than amiable ones (S3) when Taiwan attempts to

confront both the US and China.

Finally, when Taiwan stands opposed to the US, a China détente with

both the US and Taiwan (S4) is preferable to one hostile to the

rest (S6) since the former is only one step to peace (S1)

and the later is one step to absorption (S7). The preference for

the US would take the following: S1>S0>S2>S5>S3>S4>S6>S7. We assume that peace

is the best scenario (S1) and the absorption of Taiwan by China (S7)

is the worst one in the eyes of the US.

It is arguable whether the status quo (S0) is much

desirable than an alliance with Taiwan against China (S2). During the Clinton administration, the

order seemed to have been S0>S2,

judging from the priority given to comprehensive. Nonetheless, the predisposition may be

reversed (S2>S0) if a hegemonic

China is prepared to challenge the US during the Bush administration. Given the conditions that China has

set out to confront the US and that the US is determined to retain

affectionate relationships with Taiwan, it is not obvious whether it is

preferable for the US that Taiwan would seek cooperative relationship with

China or not. We may probe the

ranking from two perspectives.

Firstly, the triangle where an alliance with Taiwan is formed (S2)

is more stable than one where Taiwan would keep equal distance with both the

US and China (S5).

Secondly, Taiwan’s equidistance is less desirable in American

viewpoint since Taiwan would take a more active role in the triangular

interactions. Any scenarios in

short of Taiwan’s intimate association with the US (S3, S4,

and S6) are deemed acceptable given American crucial stakes in

Taiwan. If it turns out that the

US has to forge cooperative relationships with China at the expense of Taiwan,

it is preferable for the US that Taiwan stays aloof from China (S3>S4)

because it would not allow China to take a more dominant role in the

three-way maneuver. While

intrinsically unstable, an all-against-all regional configuration is less

desirable for the US than one where China manages to take an equidistance

stance towards both the US and Taiwan given the fact that the US can still

count on China to deal with Taiwan. From the above analyses, we may come up with some commonalities between the US and Taiwan in the triangular relationships among the US, Taiwan, and China. First of all, the US and Taiwan share the first choice of peace in East Asia (S1), and distaste the possibility of Taiwan being absorbed by China (S7). Secondly, they both would consider any chilly relations between them undesirable even though they differ in the preference over these possible scenarios (S3, S4, and S6). The major differences would be found in their disparate interpretations of whether the status quo is preferable. In Taiwan’s view, any improvement of the current semi-official relationships with the US is welcome, whether alliance with the US (S2) or equidistance with both the US and China (S5). As we have noticed earlier, if China makes up its mind to counter the US, an alliance with Taiwan would eventually take precedence over the status quo (S2>S0).

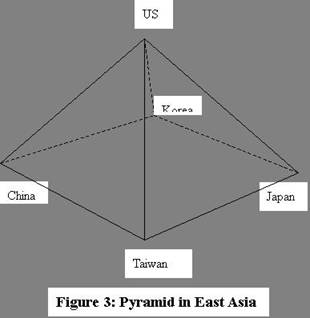

Taiwan Korea Figure 3: Pyramid in East Asia The missing link in

an emerging Taiwan-US-Japan triangle is Japan. Although the dyadic relationships

between the US and Japan and between the US and Taiwan have been robust,

conceivable linkage between Japan and Taiwan has yet failed to materialize. While the United Kingdom and France

have steadfastly maintained comfortable, if not intimate, relationships with

their former colonies, Japan has chosen to stay aloof from its only colony,

Taiwan. The Taiwanese, some of

whom still wholeheartedly harbor their romantic reminiscence of the good old

days before the war,[29][29] must have been distressed, if not

humiliated, by Japanese selective amnesia.[30][30]

On the other hand, for known reasons beyond our comprehension, our

Japanese neighbor seems content with her subservience to China, even with a

flap on the face. Equipped with

her political democracy, economic affluence, and technological supremacy,

there is no reason why Japan would refuse to become a “normal state,”[31][31] in the sense that she is willing to

contribute to peace and security in East Asia by assuming military

obligations comparable to her economic strength. Conclusions What has been left

out is the determination of the Taiwanese to seek an independent Republic of

Taiwan. As a distinct people with

its own history and national identity, the Taiwanese people have never been

offered the opportunity to exercise their right of national

self-determination. As a setter’s

state, the US share with Taiwan’s passion to breakaway

from the chains imposed it by the former land of origin since the norm of self-determination

is the highest form of human rights.

The Taiwanese have the same right to decide their destiny as the

Americans did according to the principle of people’s sovereignty. As the nation-state is still the

standard bearer of people even in the post-Cold War ear,

Taiwan, in its legitimate quest for a de

jure independent statehood, deserve its fair share in the international

arena and ought not to be deemed as a reckless troublemaker. And the future status of Taiwan should

not be confined by or linked to the terms or framework dictated by others,

especially China. With this in

mind, any effort to mediate between Taiwan and China as two separate

sovereign states that may eventually lead to peaceful resolution, not

unification, across the Taiwan Strait is welcome. Nevertheless, the

people of Taiwan need to reach a consensus on Taiwan’s future even though

they may retain dissimilar, but not necessarily contradictory, outlook of

national identity. The ruling

elite, not the US, is to be blamed for Taiwan’s isolation because of their

partisan manipulations of this issue.

After all, the US has not categorically said that it is opposed to an

independent Republic of Taiwan.

As implicitly hidden in the TRA, the law is applicable to “the

governing authorities on Taiwan recognized by the United States as the

Republic of China prior to January 1, 1979, and any successor governing

authorities.” Also the

value-loaded terms “people of Taiwan” rather than the more neutral term

“population of Taiwan’ is invariably employed in the TRA and other documents,

suggesting the prospect of any independent Taiwan if the Taiwanese should

choose to exercise their right of self-determination. Eventually, the

bottom line is whether the Taiwanese do request a nation-state of their own

choice, not any state imposed.

The real issue we are facing is Chinese irredentism to incorporate

Taiwan, not Taiwanese secession from China. After all, the current Chinese

government has never reigned on Taiwan.

Nonetheless, as along as the Taiwanese consider themselves as ethnic

Chinese in primordial conceptions, racially or/and culturally, they are

mentally destined to imprison themselves in Chinese political penitentiary

and economic abyss. The ultimate

trial for the Taiwanese would be the following: if China becomes politically

democratic and economically developed, how many Taiwanese would choose to get

unified with China? How many

people would reply definitively positive? References

Adler, Emanuel, and Michael Barnett. 1998. "Security Communities in

Theoretical Perspective," in Emanuel Adler, and Michael Barnett,

eds. Security Communities,

pp. 3-28. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press. Bernstein, Richard, and Ross H. Munro. 1997. The Coming Conflict with China. New York: Vintage Books. Betts, Richard K.

1998. “Wealth, Power, and Instability: East Asia and the United States

after the Cold War,” in

Michael E. Brown, Sean M. Lynn-Jones, and Steven E. Miller, eds. East Asian Security, pp.

32-75. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press. Booth, Ken, and Steve Smith, eds. 1995. International Relations Theory

Today. Oxford: Polity Press. Cheng, Tun-jen, Chi Huang,

and Samuel S. G. Wu, eds.

1995. Inherited

Rivalry: Conflict Across the Taiwan Strait. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. Cossa, Ralph, Akiko Fukusima, Stephan Haggard, and Daniel Pinkston. 1999. “Security Multilateralism in Asia: Views from the United States and Japan.” Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, Policy Paper, No. 51, http://www. Ciaonet.org/wps/akf01/akf01.html. Dittmer, Lowell. 1991. "The Strategic Triangle: An

Elementary Game-Theoretical Analysis." World Politics, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp. 485-515. Fiemian, Yang. 1999. “Progress,

Problems, and Trends,” in Japan Center for International

Exchange, ed. New Dimensions of China-Japan-U.S. Relations, pp.

23-31. Tokyo: Japan Center for

International Exchange. Garver, John W. 1997. Face Off: China, the United States,

and Taiwan’s

Democratization. Seattle: University of Washington

Press. Heider, F. 1946. "Attitudes and Cognitive

Organization." Journal of

Psychology. Vol. 21, pp. 107-12. Jacob, Philip E., and Henry Teune. 1964. "The Integrative Process:

Guideline for Analysis of the Bases of Political Community," in Philip

E. Jacob, and Henry Teune, eds. The Integration

of Political Communities, pp. 1-45.

Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott. Katzenstein, Peter J. 1996. Cultural Norms and National

Security. Ithaca: Cornell

University Press. Roy, Denny. 1998. “Hegemon on

the Horizon? China’s Threat

to East Asian Security,” in

Michael E. Brown, Sean M. Lynn-Jones, and Steven E. Miller, eds. East Asian Security, pp.

113-32. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Press. Segal, Gerald. 1998. “East Asia and

the ‘Containment’ of China,” in Michael E. Brown, Sean M. Lynn-Jones, and Steven E. Miller,

eds. East Asian Security,

pp. 159-87. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT

Press. Shambaugh, David. 1998. “Taiwan’s Security: Maintaining Deterrence and Political Accountability,” in David Shambaugh,

ed. Contemporary Taiwan,

pp. 240-74. Oxford: Clarendon

Press. Sheng, Lijun.

2002. “Peace over the Taiwan Strait?” Security Dialogue, Vol. 33, No.

1, pp. 93-106. Tan, Alexander C., Steve

Chan, and Calvin Jillson, eds. 2001. Taiwan’s National Security: Dilemmas and Opportunities. Aldershot:

Ashgate. Tow, William T. 1994. “China and the

International Strategic System,” in Thomas W.

Robinson, and David Shambaugh, eds. Chinese Foreign Policy: Theory and

Practice, pp. 115-57. Oxford:

Clarendon Press. Vogel, Ezra F., ed. 1997. Living with China: U.S.-China

Relations in the Twenty-first Century. New York: W. W. Norton. Waltz, Kenneth N. 1979. Theory

of International Politics.

Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley. Zhao, Suisheng, ed.

1999. Across the Taiwan

Strait: Mainland China, Taiwan, and the 1995-1996 Crisis. New York: Routledge. NG黃昭堂。1998。〈台灣國家定位與國家安全〉(Taiwan’s Future and National Security)《台灣那想那利斯文》頁193-209。台北:前衛出版社。 PINGSONG平松茂雄。1998。〈台灣的安全保障與美、中、日三國的關係〉(Taiwan’s

National Security and the Triangular US-China-Japan Relations) 收於楊基銓編《台灣國家安全》頁7-20。台北:前衛出版社。 SHIEH謝聰敏。2000。〈亞洲安全與區域組織──為「亞洲共同體」催生〉(Asian Security and Regional Organization) 收於黃昭堂編《中國的武嚇與台灣的安全保障》頁53-70。台北:台日安保論壇。 SHIH 施正鋒。2001a。〈國家認同與國家安全〉(Taiwan’s National

Identity and National Security)「全民國防與國家安全學術研討會」。台北,9月13-14日,台灣國家和平安全研究協會、立法委員戴振耀國會辦公室主辦。 SHIH施正鋒。2001b。《台中美三角關係──由新現實主義到建構主義》(The Triangular Taiwan-China-the US Relations)。台北:前衛出版社。 SHIH 施正鋒。2001c。〈和平學與台灣〉(Peace Studies and Taiwan)「為台灣和平學催生學術研討會」。台北,10月13-14日,東吳大學張佛泉人權研究中心、台灣促進和平文教基金會主辦。 TIENJIOBAU 田久保忠衛。2001。〈二十一世紀日本的遠景與台灣〉(Japan’s Future

in the 21st Century and Taiwan)收於黃昭堂編《台、日、中的戰略關係》頁17-24。台北:台灣安保協會。 YUNG楊基銓,編。1999。《台灣關係法二十年》(The Taiwan Relations Act at Twentieth)。台北:前衛出版社。 YUNG楊基銓,編。1998。《台灣國家安全》(Taiwan’s National Security)。台北:前衛出版社。

* Paper delivered at the International Symposium on

National Security in West Pacific, organized by the Taiwan National Security

Institute, Taipei, August 17, 2002. |