Since the conclusion of World War II in 1945, the United States has witnessed ten administrations, from Truman to Clinton, and its relationship with Republic of China (ROC)/Taiwan has undergone fluctuating alternation. The honeymoon between the two countries from the war-time alliance plumped to the lowest point in 1949 when the Truman administration adopted its hand-off policy toward the Chinese civil war and waited to see the annexation of Taiwan by the Communist Chinese. After the out-break of the Korean War, American policy was unexpectedly reversed and subsequently reached its peak in 1954, when a Mutual Defense Treaty was signed. The amiable relationship came to another slump in 1979 when the Carter administration decided to derecognize the ROC and established foreign relation with the People's Republic of China (PRC).

Regardless, a Taiwan Relation Act (TRA) was promulgated in the same year, which stands as the watershed of American policy toward Taiwan. Before the TRA, Taiwan had long been treated as but one component of the American global strategic thinking to counter the PRC. Thereafter, the US has been more inclined to look at its separate relations with Taiwan detached from China although American considerations in these days have to be constrained by Chinese claim of Taiwan’s territory in their mutual pursuit of accommodation.

One manifestation of the evolution of American policy toward Taiwan is American contemplation of the legal status of Taiwan. Until 1950 the US had persistently taken the position that Taiwan was part of China. To justify its protection of Taiwan after the outbreak of the Korean War, the Truman administration declared that the legal status of Taiwan was uncertain and should be settled internationally. The policy lasted until 1972 when the US formally acknowledged in the Shanghai Communiqu? that “all Chinese on either side of the Taiwan Strait maintain that there is only but China and Taiwan is a part of China." This so-called “One China Policy” has been embodied in the “Three Communiques” between the PRC and the US although the contents may have varied and been subject to different interpretations over the years with changing contexts.

Since “One China Policy” does not necessarily negate the possibility of recognizing a Republic of Taiwan, which will be elaborated later, this purposeful ambiguity has left an ample space for proponents of the Taiwan Independence Movement in their pursuit of establishing an independent Republic of Taiwan.

The other manifestation is American commitment to Taiwan’s defense as stipulated in the TRA. Although the administrations since Carter have calculated to be vague over whether the US would send troops to defend Taiwan in case of war, peaceful resolutions between the Straits of Taiwan has so far been faithfully followed, which was vividly demonstrated in the 1995-96 Missile Crises.

Nonetheless, after the recent visit of China by Clinton and his explicit spell of the so-called “Three No’s” in last summer, the people of Taiwanese began to wonder whether American policy toward Taiwan has been consistent and whether there are any continuities. Put it other way around, has there been any fundamental change in American policy toward Taiwan? If yes, the task of this analysis is to find appropriate variables to explain these changes in a systematic way.

I shall start with a recapitulation of past American policy toward Taiwan since the Truman administration. Secondly, a brief discussion of several potentially plausible explanatory variables of foreign policy will be in order. Thirdly, a Realist-Structural perspective, which argues that systemic factors have in great part dominated in this context, is laid out as the conceptual framework of investigation. Finally, a Constructivist perspective, which makes a plea for due attention to the zeal of the Taiwanese people besides power politics, is rendered as a potential guidance for the future relations between the US and Taiwan.

Evolving American Policy toward Taiwan

Historical Background: Before Japan occupied Taiwan in 1895, some American businessmen had reckoned the annexation of Taiwan. Commodore Perry also made the same recommendation to the American government, pointing out the island's strategic value. During World War II, when Taiwan was still ruled by Japan, three options were once considered for the future of Taiwan: allowing for its independence, returning it to China, or introducing an allied trusteeship. In the end, it was resolved both by Roosevelt and later by Truman to return the island to China, and the decision was later confirmed openly in the non-binding Cairo Declaration of 1943 and in the Potsdam Proclamation of 1945. It was therefore not surprising that the Truman administration did not take it seriously when the native Taiwanese sought help from the US in their 1947 revolt (February 28 Incident) against the ruling Nationalist Chinese (KMT), who took over the island from Japan after the war.

The Truman Administration (1945-53) ─ Defending Taiwan with Reluctance: After failing to mediate the struggle between the KMT and the Communist Chinese (CCP), Truman was determined to avoid further involvement in the Chinese civil war. It was thus decided to abandon Chiang Kai-shek's China.

Before the KMT was defeated by the CCP in 1949, Gen. Wedmeyer raised again the idea of a UN trusteeship or a US guardianship for Taiwan, which was again never taken seriously. When the KMT took refugee in Taiwan in 1949, it was generally expected that it soon would be taken over by the CCP. Truman declared in January 1950 that Taiwan was a part of China and that the US would not provide military assistance to the Nationalist troops on Taiwan. The suggestion to hold a UN plebiscite was also rejected by the Department of State subsequently.

Still, not everyone in the Truman administration agreed with him to abandon Taiwan. Kennan, for instance, being equally unsympathetic to the KMT, he was opposed to giving up Taiwan and preferred to leave it to Japan and indirectly to the US although he did recognize the existence of hostility between the PRC and the USSR. The perception of deteriorating American credibility must have contributed to Truman’s reassessment of Taiwan policy in 1950.

Domestic politics played a catalytic role in the Truman administration’s reversal of his policy to give up Taiwan. In the 1948 election year, Truman was harshly under attack by the Republicans, who charged that Roosevelt had sold out East Europe and Truman had sold out China. Being afraid that Congress would vote against his European Security plan, Truman was obliged to keep on providing the KMT economic and military aids. Two weeks after his being elected, he abruptly turned down Chiang's request for more aid. But until June 1950, Truman still had to make a stand against strong pressure from the Republican to provide defense commitment to Taiwan. Domestic politics must have made him prudent in his withdrawing support from the KMT.

Yet the most important factor that had changed Truman's mind was the Korean War. Three days after the war, the Seventh Fleet was dispatched to protect Taiwan. Truman reversed his earlier position and announced that the status of Taiwan was uncertain. What changed his mind? Gaddis argued that it was the concern over possible Soviet bases on Taiwan controlled by the PRC. George and Smoke provided a better explanation: protecting South Korea without protecting Taiwan was “inconceivable,” especially facing strong domestic critics of Truman’s China policy.

The Eisenhower Administration (1953-61) ─ Military Alliance through the Mutual Defense Treaty: As is well known, Eisenhower and Dulles' strategy was to surround the USSR and China with allies as instrument of deterrence around the world. The SEATO, the CENTO, and the bilateral defense treaties with South Korea and Taiwan were thus signed. Eisenhower disagreed with Truman’s China policy, but he felt no necessity to attack China as other Republicans did.

A Mutual Defense Treaty between the US and the ROC was signed in 1954. And a Formosa Resolution was passed the next year authorizing the president to employ armed forces to defend Taiwan. Missiles that could carry nuclear warheads were provided to Taiwan in 1957. In the 1958 Second Quemoy Crises, Eisenhower was not hesitant to show his determination to use nuclear weapons if necessary. The relationship between the two countries thus reached another peak.

Even though the PRC once demonstrated its willing to communicate with the US in the 1955 Bandung conference by implying that it would not use forces to liberate Taiwan, Eisenhower seemed untouched. Dulles restated firm American support for the KMT in 1957 and objected to recognition of the PRC. Why did he so unconditionally support Taiwan? Gaddis observed that it was not due to his ideological rigidity but his efforts to “split two communists by exhausting the junior partner, forcing it to make demands its senior ally could not meet.”

Kennedy and Johnson Administrations (1961-63, 1963-69) ─ Closer Relations in Global Transformation: Since the end of World War II, the US had at times considered playing upon China as a counterweight against the USSR; but the Korean War destroyed Truman's hope of rapprochement with China. The relationship between China and the Soviet Union, as communist partners, began to deteriorate in the 1950s, and military conflict was seen in 1969 over border dispute, which led to rapprochement between China and the US.

The Eisenhower administration had managed to contact China since 1955 and held ambassador-level talks in Geneva and later in Warsaw, with limited success. Although the Kennedy administration was less hostile to China, he was, as Gaddis observes, more pragmatic and against the tendency to look at any turmoil as inspired by communists. Once inaugurated in 1960, he began to notice ideological conflict between China and the USSR and attempted to improve relationship with China but received cool response. Further, his efforts at embarking on new China policy failed as Congress and public criticism resisted. Therefore, while he may not have been sympathetic to the KMT, he equally did not want to risk domestic political stability in attempting to recognize China. As the Vietnam War postponed the possibility of any compromise with China once again as did the Korean War, the relations between the US and Taiwan were ever drawn closer than before.

The Nixon and Ford Administrations (1969-74, 1974-77) ─ Neglecting Taiwan in Approaching China: The overture to court China was actively sought by the Nixon administration. The first motivation was an effort to resolve the Vietnam War by requiring China to take the place of the US. The second factor was change of American global strategy from fighting a two-and-half war to a one-and-half war. Once it was recognized that China was a crucial element in the global game of balance-of-power that was advantageous to the US, it was decided that China should not be defeated. Rapprochement was inevitable regardless whoever was in office.

It was exactly during the administration of Nixon, whom the KMT deemed as a staunch anticommunist and who once hold Truman for the responsibility of losing China, that the relationship between the US and Taiwan was descending. For instance, Congress repealed the Formosa Resolution in 1974; one of the two squadrons of F-4 jet fighters was removed in 1974. When Saigon fell in 1975, Ford declared that his aim was to "reaffirm our commitment to Taiwan." One month later, nevertheless, the other F-4 squadrons were removed.

In recollection, during the Nixon and Ford administrations, the US was essentially inclined to espouse a “Two Chinas Policy.” The final crush had yet to come from the Cater administration.

The Carter Administration (1977-81) ─ Derecognizing Taiwan: Carter's acceleration of recognition of China, according to Brzezinski, was due to his disappointment in detente. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan seemed to further convince him the primacy of normalization with China.

The US announced its decision to derecognize Taiwan on 15 December 1978. When asked by reporters why the American Ambassador woke up Chiang Ching-kuo at the midnight, Brzezinski seemed astonished to reply: “I would say they were given probably more than six years notice. After all President Nixon...in the Shanghai Communiqu?, foreshadowed this.” The Mutual Defense Treaty of 1954 was terminated the next year. Two months later, having gained tacit agreement from the US, China waged its war of punishment against Vietnam. The US also seemed satisfied that China was able to tie down 50 Soviet divisions of troops.

The Reagan and Bush Administrations (1981-89, 1989-93) ─ Disenchantment in Euphoria: When Republican Reagan, who blamed Carter mercilessly for abandoning the ROC and pledged to upgrade American relations with Taiwan, was elected, the KMT celebrated that their man had at long last come to power. Although Reagan had personal attachment to and shared the same ideological predisposition with the KMT, he failed to fulfill his promises. Preoccupied with further improvement of American relations with China, Reagan signed a Second Shanghai Communique (817 Communique) in 1982 pledging to reduce arms sales to Taiwan gradually while rejecting Taiwan’s request to purchase 150 FX’s.

With a career in the Foreign Service, Bush had his personal attachment to China although he also shared a strong feeling toward Taiwan. Being eager for further accommodation with the PRC, he hurried to China as soon as elected. Although the so-called “Taiwan Card” was raised when Tiananmen Incident took place, Taiwan was basically seen as a barrier to American “constructive engagement” with China. Especially in the wake the shatter of the Soviet Empire, the US, pursuing the newly designed and yet seemingly faint “New World Order,” had to deal with China face to face rather than from the old triangle perspective.

Nonetheless, encountering mounting pressure from business interests in 1992 reelection, Bush had no choice but to give consent to the sale of 150 F16’s to Taiwan and sent American Trade Representative Clara Hills to visit Taiwan, the first such an official visit since 1979. Since this sale contradicted what was specified in the 817 Communique, it appeared that the TRA took precedence of the 817 Communique, a disposition the US had endeavored to avoided disclosure. To sum up, Reagan and Bush took a more balanced handling between China and Taiwan.

The Clinton Administration (1993-) ─ Three No’s out of Ambiguity: To the dismay of the KMT, Democrat Clinton, although having attacking Bush for his appeasement of the Butcher in Peking during presidential campaigns, tends to give emphasis to China at the expense of Taiwan. Seeking a constructive strategic partnership with China in the short term, Clinton’s strategy of “Comprehensive Engagement” in the post-Cold War era has essentially followed his former administrations’ footsteps, while his policy toward Taiwan, judging from his 1994 Taiwan Policy Review, by and large remains the same. Basically a domestic president, Clinton’s foreign policy has been characterized as lacking any grand strategy.

It is understandable that Clinton is unwilling to upgrade American relations with Taiwan for fear of offending China. However, facing pressure from Congress, Clinton was forced to agree with Lee Teng-hui’s visit at Cornell University. It was also Clinton who send Nimitz and Independence to deter China during the 1996 Missile Crises, testifying again that the security of Taiwan as guaranteed in the TRA outweighs other policy considerations. In this sense, Clinton is right to say that his policy toward Taiwan has steered the same course.

Still, Clinton has added some ingredients into the cross-strait relations. While former presidents would prefer the status quo and refrain from becoming a self-acclaimed mediator between China and Taiwan, Clinton seems content to encourage, if not to drive, Taiwan to resume dialogue with China. Further, his interpretation of the “One China Policy” also breaks the intended ambiguity veiled in the three Communiques with China. While Clinton’s predecessors would acknowledge the Chinese position “that there is but one China and Taiwan is a part of China,” the blunt, if not reckless, Clinton administration is more ready to recognize it.

The final devastating punch come from the “Three No’s” during Clinton’s visit in China. At noted by the Clinton administration, the “Three No’s” seem to have been deposited in the Three Communiques with China. However, the strongest phrases ever used is “has no intention of … pursuing a policy of ‘two Chinas’ or ‘One China,’” rather than the explicit expression “does not support” an independent Taiwan. If the selection of the expressions was purposeful, Taiwan needs to discern what message Clinton is conveying.

Assessment ─ Peace in Short of Unification: Rationally speaking, one China carries a host of connotations along the spectrum from One China=PRC (Taiwan incorporated), One China=Two Governments (CCP & KMT), One China=ROC, One China=Historical, Cultural, Geographical China, and One China+One Taiwan. Still, it must be pointed out that the TRA has no such a phrase as “Taiwan is a part of China.” Since not all interpretations are contradictory, the US has long chosen to keep all options open to be decided by Taiwan and China themselves. This is the part of American policy toward Taiwan that seems to have been subject to periodic minor modifications but fundamentally has stayed intact since 1979.

What remains to be seen is whether or not the US would protect, if not send troops to Taiwan in case China invades the island after Taiwan formally declares independence. The US has designated in the TRA that the security issue of Taiwan is beyond any challenge although there has no formal relations between the US and Taiwan since 1979. Repeatedly, the TRA has been unconditionally invoked to demonstrate American commitment to defend Taiwan, suggesting its primacy over the 817 Communiqu?. This entrustment is further reinforced after the revised U.S.-Japan Defense Guideline was promulgated in 1997. In reality, the relations between the US and Taiwan amount to a quasi-alliance in short of the status of free association in the past 20 years. The answer to the above question is thus definitely positive. Exploring Some Explanatory Variables

Ideology: The KMT regime on Taiwan had in the past a partisan misperception of how ideology played in American foreign policy. During the heyday of the containment policy, Taiwan was invariably self-portrayed as an anticommunist warrior in East Asia and won fervent support in Congress by the conservative Republicans. The belief may have carried some face value and a pattern may be discerned: when the Republican was in office the relationship between the US and Taiwan tended to be cordial, and when the Democrat was in power the link tended to be aloof. We thus find that it was the Republican Eisenhower administration that initiated the defense treaty with Taiwan. Also it is interesting to notice that the only president who had visited Taiwan during his presidency was Republican Eisenhower. The loyal supporters of the KMT and the remainder of the so-called Chinese Lobbyist were invariably Republicans, such as Senator Goldwater. Their moral support was especially momentous when the Taiwan Relation Act was legislated after the Carter administration broke tie with Taiwan.

On the contrary, it was Democrat Truman who "sold out" the KMT in their struggle with the CCP. Again it was Democrat Carter who "betrayed" Taiwan and established foreign relationship with its foe, the PRC. For the KMT, it had always been Democrats, such as Rep. Solarz (N.Y.) and Sen. Kennedy (Mass.), who are critical of its abuse of human rights. Now, it is exactly Democrat Clinton who broke the past ambiguity and publicized the “Three No’s” formally to Taiwan’s disillusion.

But this over-simplified ideological/partisan theory fails to explain why it was Democrat Truman who dispatched the Seventh Fleet to patrol the Strait of Taiwan, and thus kept the KMT regime from collapsing. It is also unable to account for why it was Republican Nixon who started overtures with the PRC and why Republican Reagan signed the self-contradictory 817 Communiqu? (Second Shanghai Communique) according the gradual reduction of arms sales to Taiwan. In addition, it was Democrat Clinton who dispatched aircraft carriers to deter the PRC in the 1995-96 Missile Crises.

Domestic Politics: Closely related to ideology is the leverage of domestic politics, or more specifically elite and/or public opinion. When the KMT was ousted, Truman had difficulty explaining “who lost China.” This factor partially explained why he eventually decided to defend Taiwan, although the decisive factor was the Korean War. The pass of the TRA must have revealed bipartisan opposition to Carter’s abrupt abandonment of Taiwan without proper measures to ensure Taiwan’s continued survival. Facing his own reelection with the both Houses in Congress controlled by the Republicans, Clinton was forced to permit Lee Teng-hui to visit the US in June 1995.

However, foreign policy making in the US has largely lied within the discretion of the administration. For instance, Congress passed the Dole-Stone Amendment of the International Security Act in 1978, which called for “prior consultation” on any proposed policy changes regarding the Defense Treaty. Still, its lack of enforcing power on the President was evidently shown when Carter decided to scratch the Defense Treaty with Taiwan hastily. Few in Congress were actually against the recognition of China and the suspension of formal security commitment to Taiwan. Moreover, both elite and public opinion may also have shifted with the President. Domestic politics in any form is thus a constraining but not the most important explanatory variable in terms of American policy toward Taiwan.

Bureaucratic Competition: As in the case of Japan, adequate evidence shows that the Pentagon has tended to support a pro-Taiwan policy while the State Department has been more inclined to stand aloof from, if not hostile to Taiwan in their preoccupation with accommodating the PRC. The former attitudes do reflect their concerns over the maintenance of security and stability in the Western Pacific region in general and over the preservation of American military facilities in Japan, in particular.

The KMT had hitherto been obsessed with the geo-strategic importance of Taiwan for American interests and for the defense of the "free world," meaning the Asian rim extending from Japan, the Ryukyus, the Philippines, and to Southeast Asia. This perception started with Gen. MacArthur's characterization of the island as the "unsinkable aircraft carrier." During the Cold War era, when the strategic importance of Taiwan coincided with American determination to contain the Chinese expansionism, Taiwan would provide air bases and pilots for American aerial surveillance planes.

However, as the US was determined to disengage itself from the Vietnam War, Taiwan's strategic importance was decreasing. When strategic importance of China was sought, there was no necessity to contain China, and the American defense line was moved westwards, Taiwan's weight naturally became secondary. The defense arrangement with Taiwan seemed to be dispensable. In appearance, it seems that the tactical calculation of the Pentagon has never outweighed global strategic consideration.

Still, in the post-Cold War era, when the US no longer needs to ally itself with the PRC to contain the now demised Soviet Union (USSR), the defense of Taiwan seems to surge to the front again. Clinton’s determination to defend Taiwan not only demonstrates that the Pentagon was in the right but also that the incorporation of Taiwan by the PRC is unacceptable to the US.

A Structural Realist Perspective

I shall posit that American foreign policy since 1945 has been determined by its calculation of national interests, defined mainly in terms of national security. The consideration of national interests, however, is constrained by the international system. When the structure of the system changes, the US has to adjust its foreign policy to meet the new structural constraints in order to maintain its interests.

This structural perspective is not operating in isolation. Other factors, such as ideology, domestic politics, bureaucracy competition, and so on, may go hand in hand with systemic factors and may slightly adjust the policy derived from systemic consideration. But it is systemic factors that dominate American foreign policy making, particularly in the case of its Taiwan policy. When ideology and national interests, for instance, are congruent, they reinforce each other in the rationalization of certain policy outputs, usually favorable to Taiwan. On the other hand, when the commitment to ideology conflicts with national interests, the latter is usually the final arbitrator, which will generally generate unfavorable policy toward Taiwan. In this case, the relationship between ideology and foreign policy seems spurious. And if we control for systemic factors, we may find that there is slight relationship left between ideology and foreign policy at all. In this way, it is not too much to state that the most crucial explanatory variable is national interests, which are constrained by the structure of the system.

In the period of 1945-91, the global triangle was composed of the US, the USSR, and the PRC, while the regional one in East Asia is made of the US, the PRC, and the ROC. We may view the ROC-US relationship as but a link of the PRC-US-ROC triangle, which is in turns dependent on the global USSR-US-ROC triangle. When the structure of the global triangle varies, the three actors in the former triangle have to adjust among themselves.

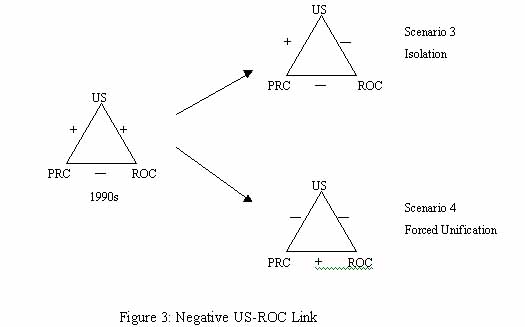

The global triangle had evolved from a balanced triangle or a quasi-bipolar (US vs. USSR+PRC) in the 1960s, to an unstable and loose triangle in the 1970s, and finally to another balanced triangle or an embryo bipolar matrix (US+PRC vs. USSR) in the 1980s. The regional PRC-US-ROC triangle had subsequently evolved from a stable one in the 1960s and, to a less degree in the 1970s, to an unstable one in the 1980s. Even with the breakup of the USSR in 1991 and the US left as the lonely superpower, the regional triangle in East Asia has largely remained the same (Figure 1).

The ROC-US relationship, evolving from tight military allies to loose partners, has basically a function of fundamental structural changes of the international system. Although the asymmetric relationship between the US and the ROC has stayed relatively the same since 1950, the stability is slightly fluctuating.

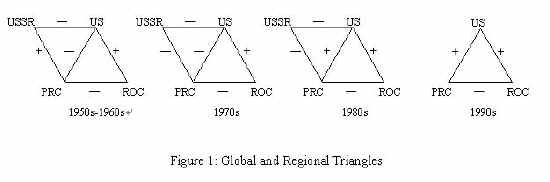

If the positive ROC-US relationship is to be maintained (Figure 2), in order to maintain a balanced regional triangle, there are two possibilities: either the PRC-ROC link is transformed into friendly one, or the PRC-US link has to shift back to inimical one as in the 1960s and 1970s. Judging from the recent development of growing strategic need and economic ties between the US and the PRC, their relationship can only grow closer and hence the latter possibility seems less probable. This leaves the former option, that is, a harmonious PRC-ROC relationship, more tenable.

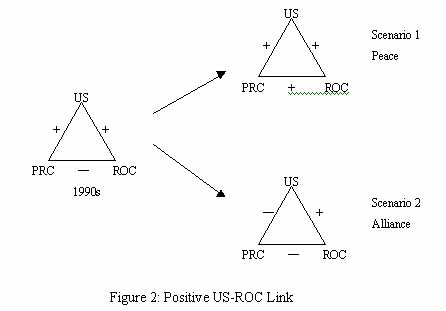

On the other hand, is it conceivable that the ROC-US relationship should turn sour or negative in the context of a balanced regional triangle (Figure 3)? One can imagine the possibility that the US should decide to embrace the PRC in all respects and to turn its back on the ROC. To attain regional balance under this configuration, the US has to sacrifice its economic tie with the ROC and scratch its moral commitment underwritten in the Taiwan Relation Act. The least plausible scenario the one that the PRC-ROC link somehow turns amicable, such as forced unification, and the PRC-US link turns hostile. This configuration is least probable in two counts: firstly, the development is not called for by the US unless it finally comes to conflict with the PRC; and secondly, a rift between the US and Taiwan is against American national interests given the enormous economic stakes on the island.